Palladio Awards 2017

Gilded Age Gem: The Veterans Room at the New York Armory

2017 Palladio Award Restoration & Renovation Winner: PBDW Architects, New York, NY

Project: The Veterans Room at the New York Armory, New York, NY

Preservation Architect and Architect of Record: PBDW Architects, New York, NY. Consulting Partner Charles A. Platt, FAIA; Partner James Seger, AIA, LEED AP; Debora Barros, associate AIA, Project Manager.

Design Architect: Herzog & de Meuron, Basel, Switzerland

Manhattan’s Park Avenue Armory, a glittering Gilded Age gem, is appointed with 18 historic rooms designed by some of the brightest shining stars of that great, optimistic century of opulence. The most majestic, the first-floor Veterans Room, was one of the early Aesthetic Movement works of Associated Artists, the creative collaboration of Louis Comfort Tiffany, Candace Wheeler, Samuel Colman and Stanford White.

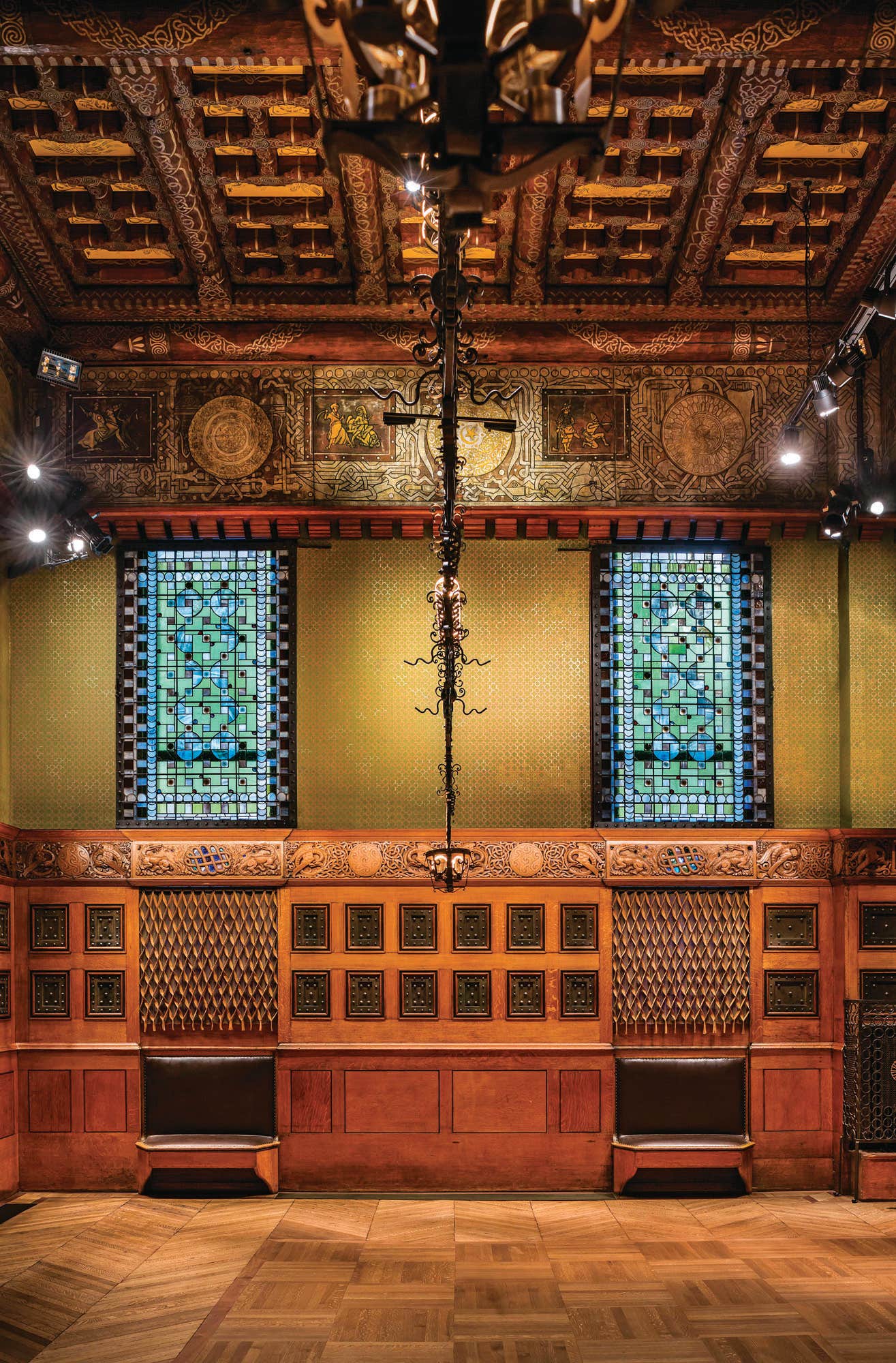

Even in an era enveloped and enthralled with ostentatious display, the Veterans Room of the so-called “Silk Stocking” Seventh Regiment, home base of the blue-blooded Vanderbilts, Van Rensselaers, Roosevelts, Stewarts, Livingstons, and Harrimans, was outstanding. In addition to a California redwood-timbered ceiling and a glass-and-plaster fireplace mosaic depicting a dramatic dragon and an antagonistic eagle, the room features Tiffany art-glass windows, Tiffany-glass tiles that change color like chameleons with the light, columns wrapped in chainmail and wallpaper stenciled to mimic precious metals.

Indeed, The New York Times heralded its opening in 1881 by declaring it “unique in its appointments and decorations and undoubtedly the most magnificent apartment of its kind in this country.” In 1992, when several rooms in the building, including the Veterans Room and the adjacent smaller library, also designed by Associated Artists, were designated interior landmarks by the New York City Landmarks Commission, its report noted that the Tiffany team’s rooms were “widely considered to be among the most significant and beautiful interiors of the American Aesthetic Movement.”

The armory itself was effusive in its description of the Veterans Room, offering that the fireplace mosaic looks “as if a bit of the Atlantic furthest from shore had been caught and pressed into service, with all its indigo held in hard, vitreous clutch.”

It was a significant room in the 1881 building, which was designed by Charles W. Clinton, a regiment veteran who became a partner of Clinton & Russell, architects of the Astor Hotel, and whose 55,000-sq.ft. drill hall is one of larger spaces of its kind in New York City.

The Veterans Room’s beauty paved the way for other major Associated Artists projects, notably the Mark Twain House in 1881; five rooms in the Chester A. Arthur White House in 1882; and the Cornelius Vanderbilt House in 1883. Associated Artists only lasted four years, and the Veterans Room sheds light on the early work of these 19th-century designers who went on to have stellar solo careers.

In 2006, the Park Avenue Armory commissioned the Swiss firm of Herzog & de Meuron as design architects and New York City-based Platt Byard Dovell White Architects (PBDW) as preservation architect and architect of record, along with a number of consultants, to develop a design vision for the building to be implemented in phases that included restoration, rehabilitation and infrastructural upgrades.

In 2014, the team was commissioned to work on the $8.9-million restoration of the Veterans Room, returning it to its delightfully delicate luster, which had been lost to time.

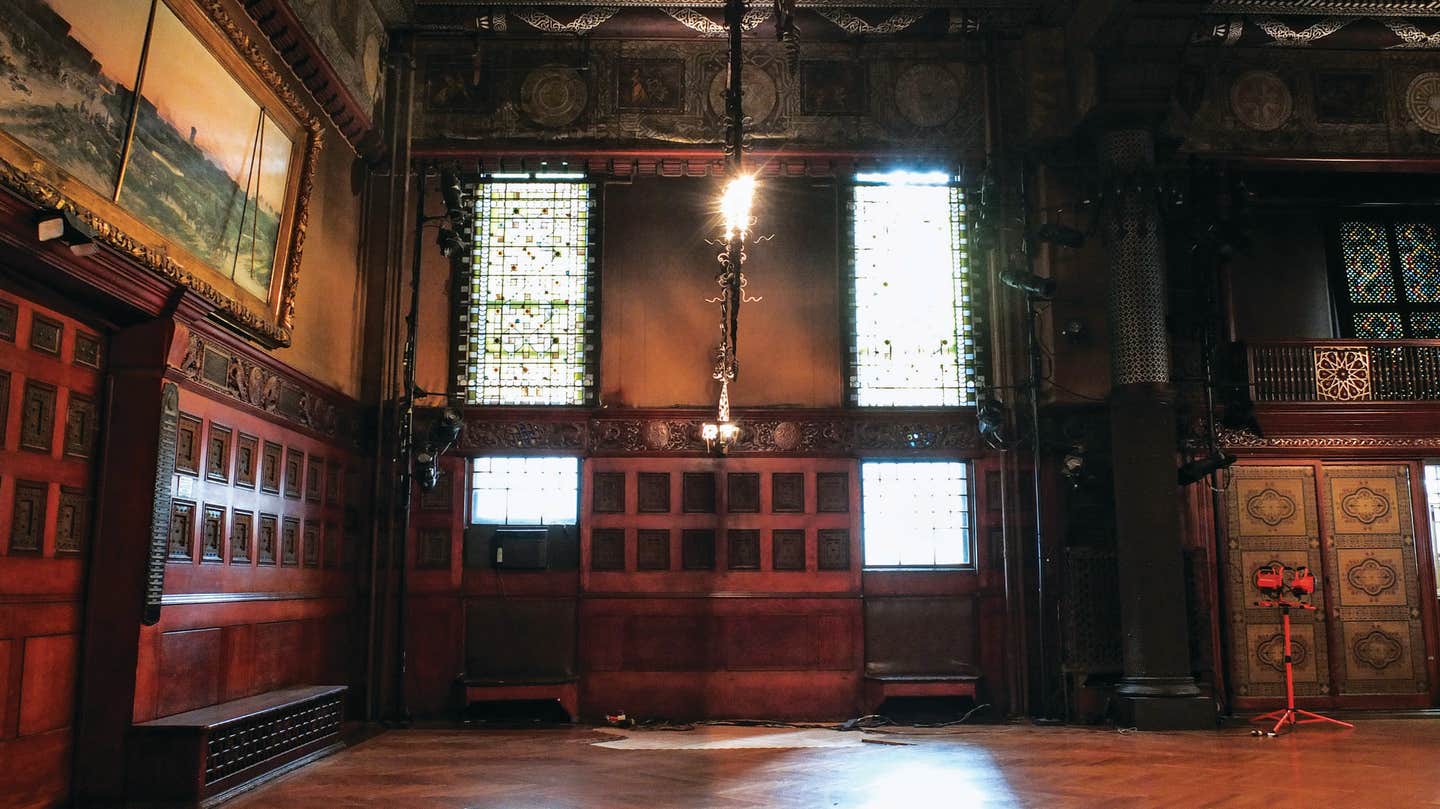

While the major elements, notably the iron light fixtures, stained-glass windows and Tiffany-glass fireplace tiles, were in place and virtually intact, original details had been obscured.

The ceiling, for instance, had been overpainted, and the Wheeler curtains, as well as the bench cushions, were long gone. The wood floor had been covered by a more modern one, which was removed, and the original was repaired and restored.

As for the wallpaper, all that remained was a roughly 10x30-ft. section that survived behind a painting. A small section of it was removed and sent to the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum’s collection, and the remainder was cleaned and protected in situ, entombed beneath a protective layer that received the newly designed wallcovering.

“Paint analysis of the original wallcovering was done by Foreground Conservation Arts, and the new wallcovering, designed by Herzog & de Meuron and created by EverGreene Architectural Arts, has a base combination of blue and green over which a series of stencils were applied in the studio to reflect the original chainmail pattern and metallic accents,” Barros says. “After it was installed, additional metallic and olive green accents were hand-applied following the more organic creative process seen in the original. The challenge was to achieve a handcrafted expression with a repeating pattern reinterpreted with the use of computers and produced in a shop.”

Replacing the draperies in the lower windows was not as easy. With no remnants of the Wheeler textiles to use as clues, the team relied upon vintage photos, and Erik Bruce Fabrik created deep blue velvet panels layered in copper mesh and leather strapping that are a contemporary take on her style.

The Tiffany art-glass windows were removed, repaired, and cleaned by Femenella Associates.

The restoration of the fireplace, the focal point of the room, was one of the more difficult parts of the project. The fireplace had shifted and settled, displacing stone sections and causing stresses to the woodwork and mantel, which were restored and reframed. “The Tiffany blue-green tiles were cleaned, numbered, largely removed, restored and reinstalled in the same sequence,” Barros says.

One of the more exuberant features of the Veterans Room is the mammoth, Medieval-style chandeliers. The originals, which had gas jets, had been updated for electricity in 1897; the later bulbs were awkward additions that detracted from the design.

As Barros says, “Herzog & de Meuron designed and beautifully reinterpreted the original gas light jets with optical lenses and gold-tone LED fixtures, making the frosted edges of the lenses glow. It’s not gaslight, but it evokes the feel of the original gaslight.”

The project, which took two years, was completed in March 2016. “The result of the work of all the designers, consultants, conservators and artisans brought back a breathtaking room that responds well to the client’s program as a performance-arts venue,” she says. “When you look at it, you can feel the talent of Associated Artists revealed to us once again.”

Key Supplies

Conservation Manager and General Contractor: Tishman Construction Co., New York, NY

Lighting Contractor: Aurora Lampworks, Brooklyn, NY

Plaster Restoration and Wallpaper: EverGreene Architectural Arts, New York, NY

Windows and Leaded-Glass Restoration: Femenella & Associates, Branchburg, NJ

Painting, Stenciling, Restoration of Decorative Frieze: Foreground Conservation & Decorative Arts, New York, NY

Fireplace Restoration: ICR, New York, NY

Metals Restoration: McKay Lodge Laboratory Fine Art Conservation, Oberlin, OH

Wood Repair and Restoration: RMA -- R Mark Adams, Lempster, NH

Overmantel Plaster and Glass Mosaic Restoration: Rosa Lowinger & Associates, Miami, FL

Floor Restoration: Haywood Berk Floor Co., New York, NY

Upholstery: Atelier de France, Glenville, NY

Draperies: Erik Bruce Fabrik, Brooklyn, NY

Structural Engineer: Silman, New York, NY

MEP Engineer: AKF Group, New York, NY

Acoustical Engineer: Akustiks, South Norwalk, CT

Lighting Designer: Fisher Marantz Stone, New York, NY

Theatrical Consultant: Fisher Dachs Associates, New York, NY