Palladio Awards 2018

Restoration of Childs’ Restaurant in Coney Island

Project: Restoration of Childs’ Restaurant and addition of Ford Amphitheater at Coney Island, Brooklyn, NY

Architect: Gerner Kronick + Valcarcel, Randolph Gerner, AIA, Principal; Joe Barbagallo, AIA, Principal; Silke Rapelius, AIA, Associate Principal; Rachel Oehl, Associate.

Preservation Consultant: Kaese Architecture, Diane Kaese, New York, NY

If you were walking along the boardwalk in Coney Island in the 1920s after visiting Luna Park, Steeplechase and other attractions, you would probably be drawn into Childs’ Restaurant by the open friendly atmosphere and the five large open windows with a baking station located in one of these. You would definitely notice the ornate terra-cotta ornament depicting maritime themes on the facade of the building.

Fast forward to 2017, and the building is back as a fine-dining restaurant and bar, with an added amphitheater and rooftop seating. It is no longer a Childs’ Restaurant, but much of the historic building has been restored and brought up to date.

One of the first fine-dining restaurant chains in the country, Childs’ was started by two brothers, Samuel S. and William Childs. Noted for cleanliness and quick and efficient service with waitresses wearing white starched aprons, the first location opened in 1898 in the Merchants Hotel on Cortlandt St. in Manhattan. By 1928, they operated 112 restaurants in 33 US and Canadian cities, according to Appetite City, a book by former New York Times food critic William Grimes published in 2010.

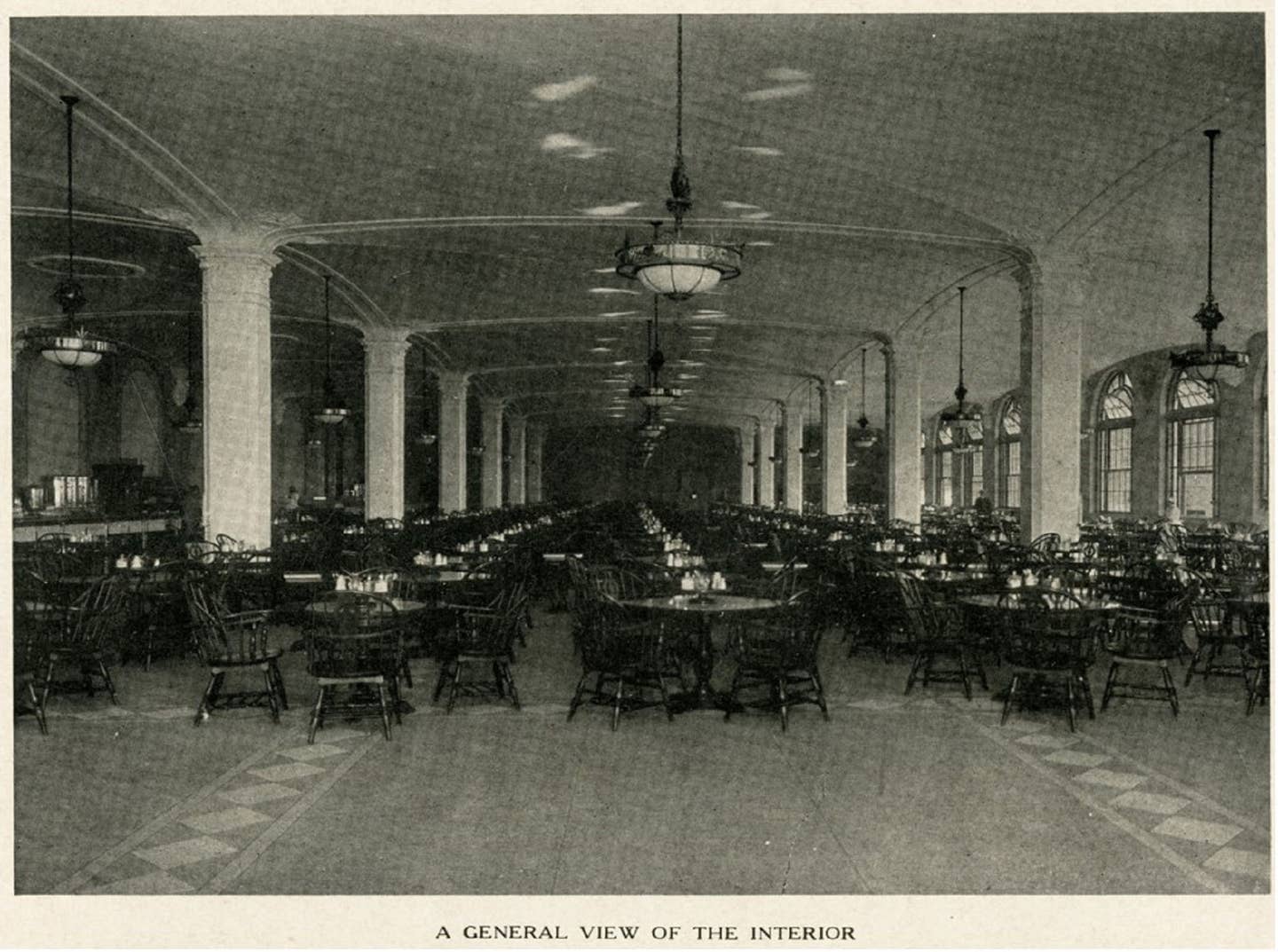

One of the more spectacular locations was the Childs’ Restaurant on the boardwalk in Brooklyn’s Coney Island. Facing the ocean, the 85,000-sq.ft. building was designed by Dennison & Hirons with Spanish Colonial Revival style elements to create a truly memorable structure.

The facade was covered with maritime terra-cotta ornament, designed to look like it had washed up out of the sea, covered with all sorts of sea life, both fanciful and realistic. More than 500 multi-colored terra-cotta castings of seaside themes such as sailing ships, rolling waves, seashells, wide-mouth smiling fish and Neptune sculptures adorned the building. The original terra cotta was modeled by Max Keck; the colorist for the project was Duncan Smith. Atlantic Terra Cotta Company produced the terra cotta.

The depression in 1930 hit Childs’ as well as other restaurant chains. Although they stayed in business a few more years, the chain filed for bankruptcy in 1943 and the Coney Island building was sold to the Ricci family in 1947. They made minor alterations to the facade of the building and manufactured candy there until 2003. About that time, the building was designated a New York City Landmark.

In its report, the Landmarks Preservation Commission described it in this way: “Across most of the main facade are five large archways which have been enclosed across their top with stucco and on the lower portion by roll-down gates.

Plain, round cement columns with terra-cotta capitals separate each arch. Non-historic murals of Coney Island scenes are located in the upper portion of four of the arches. Each arch is embellished with decorative terra cotta along the front edge and inside the reveals. The terra cotta consists of repeating, blue and green images of various fish and seashells. Four rondelles are located in the spandrels of these arches, each with maritime motifs in colorful terra cotta. There is another bay located to each side of the central arcade.”

The unique building lay vacant and neglected until 2014, when the New York City Economic Development Corp. partnered with owner iStar Financial and Coney Island USA, a nonprofit, to fund a $60-million renovation of the abandoned, derelict building.

Enter Gerner Kronick + Valcarcel, Architects, a New York City firm with a distinguished record in historic preservation. One of their recent projects was the restoration of the Beekman Hotel in Manhattan, a 2017 Palladio winning project. The program at Coney Island called for the restoration of the ornate terra-cotta exterior, a redesign of the interior to again function as a restaurant and the addition of a 5,000-seat covered outdoor amphitheater.

“Originally the borough president was looking for a site for community concerts and theatrical events, and he was hoping to do this in a band shell on the east end of Coney Island,” says Randolph Gerner, AIA, principal, Gerner Kronick + Valcarcel, Architects. “The residents objected and then the developers noticed the Childs’ building. The idea was to save the building and to create a park and a 5,000-seat amphitheater on the site. We had to go through a variety of agencies to have the site approved as an entertainment venue. It took a lot of effort to convince the different agencies, but after all was said and done, they allowed us to give the Childs’ building a new life.”

The 335 x 100 ft. building is essentially a large masonry box. While the exterior had somewhat weathered the storms of time, the interior had been gutted and little of the original material remained. The design team returned the building to its original purpose as a 2,000-sq.ft. full-service Kitchen 21 restaurant with seating for 400 and a 90-ft. bar. The ground floor below, at street level, provides support services such as a loading dock, offices and restrooms. A rooftop terrace with a pergola was added.

Gerner explains that the historic building offered quite a few challenges. “We had to take the playfulness of the original architecture, and recreate it into a new facility,” he says. “Often you change a warehouse into a residential building, but adapting a large footprint and turning it into a restaurant and theater building at the same time was a different challenge.”

To create the new amphitheater and adjacent seating area, the architects removed a portion of the west wall and inserted a stage just inside the building. The stage can be viewed from the restaurant or from the exterior seating, which is shaded with a fabric roof and also provides ocean views. During the winter months, the stage is closed off with large doors.

The addition of the stage within the existing building required other structural changes. For example, the stage tower columns had to be threaded down through the existing floor slabs to new foundations.

Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the building, the fanciful terra-cotta facade, was restored by Boston Valley Terra Cotta, working with glaze consultant, Christine Jetten, who helped develop the glazes. Diane Kaese, the historic consultant for the project, noted that “Glazing was a challenge. Extreme care was taken to match the original glazes as closely as possible. We ended up with 36 glazes after reviewing hundreds of samples.”

“The terra cotta was astonishing,” says Kaese. “I don’t classify it as terra cotta; I classify it as art. The sculpting was incredible. There was both bas-relief and three-dimensional sculpting and the pieces were huge. There are three major assemblies. Some of the individual pieces in the assemblies weighed over 300 pounds. The depth of the units varied throughout the assemblies with some pieces being more than 18 inches deep. In addition, the joints were ¼ in. wide creating very tight tolerances.”

Kaese adds: “The sophistication and humor of the installation became apparent the more we worked with the pieces. When we removed the roof leaders from the medallions, we found that the leaders covered a waterspout in the center of the medallion. Classical forms were executed with nautical motifs: egg and dart became fish and urchin. Lobsters, rather aggressive fish and happy snails all served as brackets.”

She explains that many pieces of the original terra cotta could be reused but new cartouches, medallions and the window and door surrounds had to be recreated. Existing pieces were removed and sent to Boston Valley Terra Cotta to be used as models. “There was quite a bit of algae growth which caused damage over the years and broken pieces due to the rusting of steel elements.” Kaese says.

The new terra-cotta pieces were installed using modern stainless-steel anchors. “Resetting the new terra cotta was essentially a large, three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. It was a challenge to manipulate and install the pieces with the minimal joint size. A total of 752 new terra-cotta pieces were replicated for the building, 102 were salvaged and reset, and 171 were repaired on site.”

Another challenge, she notes, was the west wall, where the amphitheater was installed “It was made of many different colors of common brick. We had a lot of freeze-thaw damage, delaminated brick faces and other damage. While a good portion of the wall was removed for the stage, we removed the outside wythe of brick and installed whole new wythe on the wall that remained. We used salvaged brick and it blended very well. The new brick is slightly harder and wasn’t a perfect match, but it was pretty darn close to the characteristics of the original common brick.”

“We also used the salvaged common brick throughout the project including to reconstruct the three-to-five wythe walls that support the terra cotta,” she adds.

When the 1960s stucco was removed from the south and east walls, numerous cracks and deteriorated steel framing for the roof rafters were revealed. After repairs, new stucco was applied to the south and east elevations, using a standard plaster system made by ConProCo. The color was selected to closely match the sand on the beach. The surface was then finished with a rough wood float to match the original design intent, Kaese explains.

Energy efficiency was another goal and it was a challenge because of the large ocean-facing windows. The architects used high-efficiency wall assemblies and glazing to achieve the desired goal and they expect to achieve LEED silver certification.

To deal with future storms, Gerner and his team used materials that would be resistant to water and storms. Acoustic draperies were also added to help keep the sound inside the building.

The new restaurant and Ford Amphitheater opened in the summer of 2017 after two years of construction. While it is no longer a Childs’ Restaurant, the spirit lives on in the restored fanciful terra-cotta facade, the new restaurant, bar and amphitheater, bringing jobs and new life to the long-neglected west end of Coney Island.

Key Suppliers

Construction Manager: Hunter Roberts Construction Group, New York, NY

Landscape Architect: Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, Brooklyn, NY

Terra Cotta Manufacturer: Boston Valley Terra Cotta, Orchard Park, NY

Masonry Contractor: Pullman SST, New York, NY

Historic Brick: Gavin Historical Bricks, Iowa City, IA