Palladio Awards 2015

BKSK Architect’s Design for a New Park House in Washington Square Park

2015 Palladio Awards Winner

New Design & Construction, less than 30,000 sq.ft.

Winner: BKSK Architects, New York, NY

PROJECT:

Park House in Washington Square Park, New York, NY

Architect:

BKSK Architects, New York City; George Schieferdecker, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, partner in charge; Harpreet Dhaliwal, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, project architect/manager; Jennifer Preston, LEED AP BD+C, director of sustainability; Paul Capece, Pranjali Desai, Christian Eusebio, project staff

LEED: registered LEED Platinum

Landscape Architecture: George Vellonakis, NYC Parks Dept.

General Contractor: AAH Construction, Astoria, NY

KEY SUPPLIERS

Corinthian granite: Champlain Stone, Warrensburg, NY

Jet Mist granite: Structural Stone Co., Inc., West Fairfield, NJ

Reclaimed wood (trellis and benches):Sawkill Lumber Co., NY, NY

Steel window system:Optimum Window, Ellenville, NY

CONSULTANTS

Structural Engineering:Weidlinger Associates

MEP Engineering & Lighting Design: Buro Happold

Civil Engineering: Michael Wein Engineer

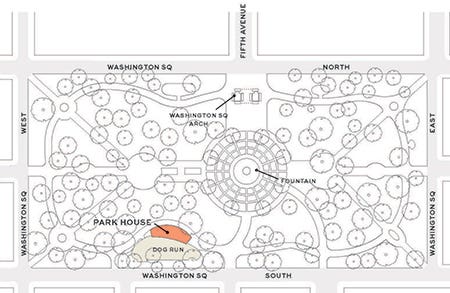

Dating from 1827, New York City’s Washington Square Park is one of the city’s most famous destinations. The almost 10-acre urban park occupies two city blocks at the foot of Fifth Ave. in the heart of Greenwich Village and is surrounded by historic architecture as well as the New York University campus. It is famous for the central fountain and the iconic arch honoring George Washington, the park’s namesake.

While everyone comes to see the people, the fountain and the views through the arch up Fifth Ave., many may also find their way to the new park house in the southwest quadrant near the dog run. The 3,100-sq.ft. building was designed by BKSK Architects of New York City to blend into its surroundings and not intrude on the primacy of the fountain and arch.

“We felt an enormous sense of responsibility because this is a very prominent place in New York City,” says George Schieferdecker, AIA, partner in charge, BKSK. “Washington Square Park has a great history, and it has been revitalized as a wonderful urban place."

He points out that the park house was carefully designed to be simple and understated. “We went through a number of schematic designs,” he says. “It became clear that we wanted to make something that was deferential to the fountain and the arch, blended into the park, and did not call attention to itself. A number of people in the Parks Department, in particular George Vellonakis, the landscape architect of the park’s renovation, were instrumental in in helping us pursue these goals.”

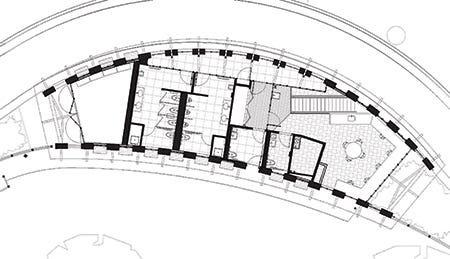

The addition of the new park house was part of the third phase of the renovation of the historic park. It houses park offices, public ADA-compliant restrooms, and maintenance facilities. Designed to have a small footprint on the land and minimal impact on the environment, the park house was partially built on top of an existing cellar. Three existing structures were demolished to make way for the new, smaller park house.

Schieferdecker explains that the Parks Department brief required the incorporation of an existing basement, a part of which housed new equipment for the park’s fountain. Simultaneously “we had to be careful because the project is located on a potter’s field, an archeological site, which mandated minimal subsurface disturbance in the area.”

The cellar, which is smaller than the new building and is located under the park offices portion of the main floor, was repurposed into a break room, men’s and women’s locker rooms, and additional rooms for mechanical equipment.

While the program was simple and the building small, the design decisions were significant. First, the decision was made to slightly change the meander of the park path so the park house could be located to the outside of the path. “The fountain and the axial configuration of the broad boardwalks crossing the center of the park are about formality,” says Schieferdecker, “and then the meandering layout of the paths around the outside of the park is about informality. We decided to position our building to the outside of the paths and, with our curved plan form, clearly remain a part of their casual order.” The location also buffers the dog run from the interior of the park.

Then the decision was made to design the building to take the form of a trellis. “The ‘trellis’ or ‘pergola’ is an archetypical park structure. Our design simply inhabits that form and occupies the trellis,” he explains. “It tapers on the ends so that as you approach it appears to have a narrow dimension and you don’t sense its mass as you walk along its curved face.” Eventually, fragrant vines will grow over the trellis and complete the appearance and effect of the design.

Schieferdecker adds: “It is amazing what you get when you work a simple form. The split columns let more light into the central zone, which is pulled back under the trellis. Everything is within that very simple trellis form.”

For the most part, the building is made of regionally sourced and recycled materials. The predominantly gray granite, flecked with white, pink, and green, that was used for the exterior columns originated in upstate New York. The trellis is made of redwood reclaimed from pickle barrels and water tower tanks, and the steel windows are made of 98.5% recycled material.

The park building’s energy is sourced in part from a solar panel array, and energy costs for elements such as heating and cooling are further reduced because of a ground source heat pump system, for a total savings of nearly 60%, Shieferdecker explains. The ground source heat pump system also eliminates the need for noisy mechanical equipment on the exterior of the building.

In addition, the offices, bathrooms, and maintenance garage all benefit from natural light. The offices have substantial views out to the park, which enhances the environment for the workers and provides additional security for the park. Low or zero-VOC (volatile organic compounds) paints, adhesives, coatings, sealers and sealants were used throughout.

The building was completed in 2014. “I think of this building as contemporary as well as traditional,” says Schieferdecker. “It is free and minimal in form, progressive in its sustainable features, but very distinctly rooted in traditional archetypes.” TB