Palladio Awards 2021

Anderson Hallas Architects: Sperry Chalet

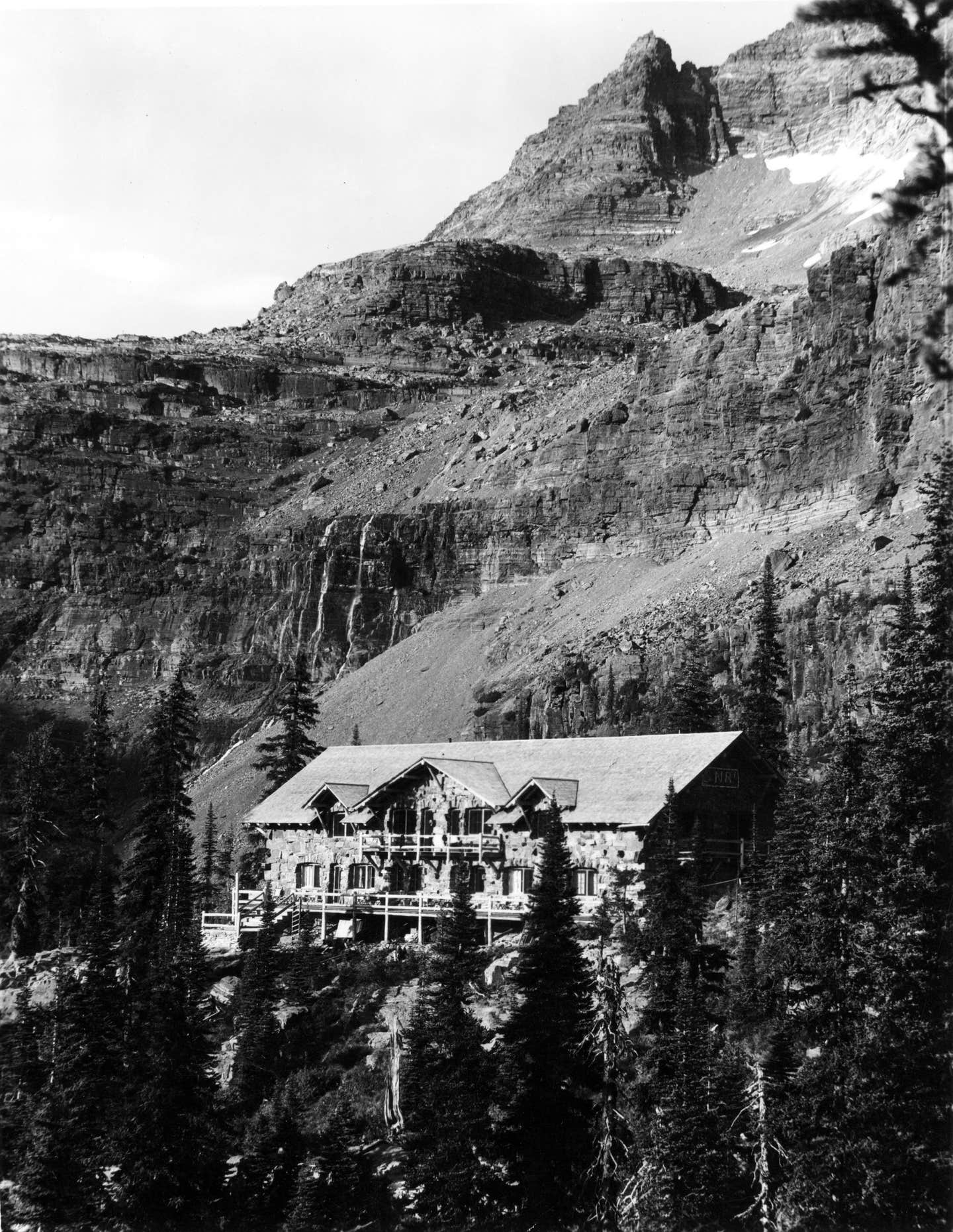

For more than a century, adventurers from around the world have trekked up a steep 6-mile trail in the wilderness of Montana’s Glacier National Park in the Rocky Mountains to stop in at Sperry Chalet for a night or two.

The 1913 chalet, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and is part of the Great Northern Railway Buildings National Historic Landmark District, is an iconic feature of the park.

When a 2017 forest fire destroyed everything but its argillite stone walls and chimneys, Anderson Hallas Architects of Golden, Colorado, was commissioned to literally raise it from the ashes.

“We were tasked by the National Park Service, in consultation with the community, the state historic preservation office and the secretary of the interior with bringing back the building’s character while meeting current building codes,” says Liz Hallas, AIA, a principal with Anderson Hallas Architects, which specializes in high-altitude restoration and rehabilitation projects.

It was as much a project about logistics as it was reconstruction and rehabilitation. The deadline was short—the chalet was to be completed in only two years—and work had to be scheduled around the weather—snow is on the ground from September through June.

The chalet is perched on a 6,500-foot-high cliff. Construction crews set up a base camp of tents raised on platforms (grizzlies and other bears are common, and mountain goats were often spotted roaming through the wreckage), and two teams of workers lived on-site in three-day shifts. Building materials were delivered via helicopter or by mule.

“The project estimated over 200 tons of materials with hundreds of helicopter flights and 35 to 60 mule pack strings each construction season,” she says. “The mules were outfitted with large trash-can bins on each side; the weight had to be evenly distributed, and each mule could only haul 150 pounds at a time.”

The team studied period and recent photos of the chalet’s exterior and interior, reconfiguring the steep, narrow central staircase into a long L shape to meet code requirements and slightly modifying room floor plans of the 17 guest rooms.

Although the remaining stone was structurally sound, the fire had caused it to spall, and melting tar from the previous asphalt roof had stained it.

“We scraped nearly two inches of the fractured interior stone off for safety,” Hallas says, adding that the team got special permission to use the original quarry, which is located right above the chalet on the mountainside, for replacement stones that were hand-selected by masons.

Safety-code upgrades were incorporated in a discreet manner that doesn’t detract from the chalet’s historic-centric design.

The timber-log beams and rafters of the original chalet were recreated from local timber, but sections of steel were concealed inside to comply with modern code for seismic, snow, and wind loads.

Because there’s no water supply at the chalet’s remote site, it was not possible to install a fire-suppression system. Given that fact, the team decided not to introduce any “spark-inducing” features in the building, which did not have plumbing or electricity in recent years.

The cedar-shingle roof was upgraded to a Class A roofing assembly, and the walls between the guest rooms were redesigned as one-hour fire partitions before wood trim and finishes were added.

Hallas notes that fundraising for the $8.8-million project was an international collaborative effort. The Glacier National Park Conservancy formed a “save-the-chalet” fund that collected over $700,000 in donations from 1,261 individuals.

“People from 48 of the 50 states as well as from around the world sent money,” she says. “And the National Park Service supplemented the budget with emergency funding.”

She adds that the in-kind donations included helicopter-training flights to deliver construction materials and notes that the “2017 Congressional Christmas Tree was fashioned into newel posts for the newly framed stairs.”

The contractors, she says, deserve special recognition. “There was a collaborative spirit among all involved; everyone brought their A-game to the project,” she says.

The Sperry Chalet opened, right on time, in the summer of 2020.

“It’s a beloved project and a beloved site,” Hallas says. “It’s a really special place. For people who are lucky enough to have the opportunity to visit Sperry Chalet, it sticks with you during your lifetime. And bringing it back to life will stick with me through my lifetime.”

KEY SUPPLIERS

Architect: Anderson Hallas Architects

Construction: Dick Anderson Construction

Structural Engineer: JVA Engineering

Electrical Engineer: AE Design Group

Civil Engineer: Martin/Martin Consulting Engineers

Geotechnical Engineer: Yeh & Associates

Masonry Specialist: Atkinson Noland & Associates

Masonry Contractor: Anderson Masonry

Log Supplier: Pioneer Log and Timber Homes

Construction Logistics: Onsite Management

Reproduction Windows: Parrett Windows and Doors

Interior Doors: Pacific Rim Sash and Door

Reproduction Doorknobs: Nostalgic Warehouse

Paint and Stain: Sherwin-Williams

Self-Luminous Exit Signs: Evenlite