Carroll William Westfall

The Disappointing Federal Reserve Building

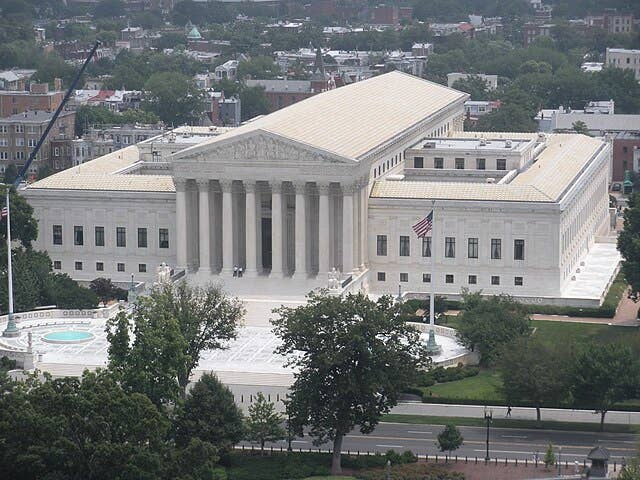

Facing the National Mall the Federal Reserve System’s building presents a style acceptable to both Modernist and traditional architects. Its architect Paul Cret had studied at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris and had been recruited in 1903 to establish the architecture program at the University of Pennsylvania.

Modernists see its style as stripped or starved classicism. Taught to see ornament as crime, they relish its near absence. Profiles and parts such as a frieze are drastically diluted or even excised. Four piers substituting for columns and no pediment mark the entrance’s membrature. The thinnest possible cornices describe the pediment of the diminished, solitary portal. And the windows on the flanks have meager cornices, reach crisp corners, and rise three stories from sills that merge with the basement coping. Like the square attic windows they are merely holes in the smooth, white Georgian marble facing.

Despite this scouring of the ornament at what is officially called the Eccles Building, traditionalists see enough to find some satisfaction. The building’s configuration and membrature is composed as a three-part façade on a well-proportioned carcass familiar from the central section of the original Capitol’s east front, the White House, Thomas Jefferson’s revised Monticello, and so on. A propylaea substituting for a temple front is attached to a volume complete with a bump breaking the silhouette. Slight projections firmly attach the long side flanks. In other eras these might have held cells for priests, monks, or nuns; here government workers work with natural light from the front, rear, or courtyards extending out into an extensive setting. (The courtyards are soon to be filled, and a five-story addition is scheduled for the rear with assurances that this will not disfigure the building.)

Any beginning student at the École de Beaux Arts could have roughed out that design, but missing from it is the evocative power of the classical that has served the nation since itsfounding and reaching its American finale across the Mall at John Russell Pope’s Jefferson Memorial built despite Modernists’ protestations.

While traditionalists can accept the style of Cret’s building, they ought to see it as a betrayal of architecture’s purpose. In considering its style as classical enough, they endorse the role of style. A style is merely a descriptive term for formal properties. They ignore Demetri Porphyrios’s reminder that “Classicism is not a Style,” and they accept the Modernist notion thata building’s style is architecture’s most important aspect even though it merely documents the moment when influences dictated the building’s appearance did their work.

But buildings, even Modernist ones, actually result from decisions made by builders and architects, and in using Modernism, they disregard the fact that buildings, both public and private alike, will not be unseen in the public realm. For them, the public realm is simply an arena where they pursue their private ends. More often than not, those ends amount to serving the builder’s self-interest and the exhibition of the architect’s creativity. A building necessarily occupies a public realm. Its construction requires approval, and it must not threaten or harm public health, safety, and general welfare. Once built, it cannot be unseen. And it is under no obligation to improve the quality of the urbanism it joins. To do so it must be an example of good traditional architecture that establishes connections with traditions that elevate the art of building to the art of architecture and carry the requisite symbolic content that serves and expresses its contribution of its good purpose in our lives. We might here think of the art of architecture being to the art of building what the art of politics is to legislating and executing, as a means of serving the common good.

Beginning in the 18th c. the connection of buildings with the beautiful began to weaken. In identifying a building, style gradually replaced the role of the columnar orders or more general terms that identified its purpose. In the early modern period when the range of purposes to be served began expanding, architects responded by inventing and innovating within formal traditions to identify, serve, and express them. Like those who governed the public realm, they sought a judicious synthesis of continuity and innovation, of tradition and invention. In architecture as in governing, whether monarchic, autocratic or democratic, authority flows down from a center and out to its many members and branches—parent to child, teacher to student, king to subject, president and legislature to a democratic citizenry, and so too in architecture, Versailles to innumerable chateaux, our Capitol to many state capitols and even city halls, and the U. S. Treasury Building to innumerable banks. Just as the purpose sought to provide and protect the good so did the building provide an example of the beautiful.

Modernism rejected that program. It was even erased it from the narrative of the history of architecture. Architects learned that cultural and other influences and popular formal models invented within Modernism’s styles determined styles in art of personal expression as they designed buildings to serve short-term functions. The narrative taught that the ongoing invention of new styles would hurry the future away from the lamentable past, with kudos reserved for the creative few who attract the most followers.

The Federal Reserve System was established following turmoil in the banking industry. Established in 1913 with a home in the Treasury Building that Robert Mills began in 1836. The purposes of this important intrusion into commerce’s private business were to maximize employment, stabilize prices, and supervise and regulate banks and the money supply. A photomontage from 1936 pictures the headquarters of its 12 regions seats, each a full embrace of the nation’s classical architectural traditions that express the authority of federal institutions within our democratic republic that itself descends from antiquity in a tradition undergoing constant adaptations to changing circumstances.

The Depression was a period of major commercial turmoil that produced major reforms in the nation’s commercial affairs. By now, the nation’s corporate capitalist system was embedded in the nation’s democratic political system. In 1903 George B. Post’s New York Stock Exchange, a private corporation, was built on Wall Street where it was operating when the nation was founded. Capitalism began to be challenged by various socialist and other collectivist central European alternatives. New protectionist programs were launched that intruded directly into the nation’s commercial system. In 1933 came the Securities and Exchange Commission for “protecting investors, maintaining fair, orderly, and efficient markets, and facilitating capital formation.” And in 1935 the Federal Reserve was reformed and strengthened and provided with its new headquarters opened in 1937.

As Modernism eased its way into the world of private commercial activity, other builders, public and private, followed. The Fed’s desiccated classicism portended government’s alignment with corporate commercial forces, and in the post-war recovery, Modernist styles achieved near hegemonic roles in commercial buildings and in public ones as well. Many of the Fed’s regional branches, the SEC, and other branches including courts, now operate in Modernist glassy high rises. The Modernism serving the functions of commerce, culture and even governing lack the gravitas that government authority requires to be convincing. To be efficacious, authority must project its commitment to the good; otherwise, its demands and guidance can be dismissed as being as arbitrary and even capricious as the buildings serving it.

Modernist architecture cannot project gravitas. Brutalism proves that. The Federal Reserve Building’s modernism was a harbinger that is now in full force. Only traditional architecture can carry the gravitas that assures citizens of authority’s legitimacy. And it must be the full classical presence in the configuration, membrature, and ornamentation. Anything less deprives the public of the urbanism devoted to serving the public good and instead presents the public realm as an arena for putting private interests in first place and undermines the quest for a More Perfect Union within a tradition that is being constantly adjusted to serve the present.

The political and cultural progress that we enjoy results from choices made by generations of individuals committed to the common good. They anchored the political realmwithin a tradition that honors and revises the applications of enduring truths and interpretations of the good. But while those prevail today, architects opt out. New federal buildings, most egregiously courts and the Fed’s new regional headquarters, lack gravitas as they compete for attention with eye-catching starchitects inventions or settle for cheaply built commercial office buildings. Some banks stand as glistening high rises in the city’s center, other as suburban retail outlets resembling toll road payment stations or merely a protective rain shelter for an ATM, but none chose to participate in a tradition of civil architecture that includes the palace that the banker Cosimo de’ Medici built for doing business in Florence.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.