Carroll William Westfall

Restoring Beauty to Federal Buildings

We can expect the new administration to pursue its program to establish classical architecture as the preferred architecture for federal buildings. The Republican attempt four years ago was beaten back by the outrage of the architecture profession and the professional and popular press. The New York Times identified its sponsors as “small-minded classicists;” they were, in fact, a minority faction addressing a very popular issue.

Their first stab was with an Executive Order that President Trump issued at the very end of his presidency and Joe Biden immediately annulled. In 2024 the issue reappeared in the Republican Platform’s promise to “Make Washington D.C the … Most Beautiful Capital City [and] promote beauty in Public Architecture,” a topic absent from the Democratic side.

The program seeks to replace Modernist styles for new federal buildings with classical architecture. In the richest, deepest, and broadest understanding, classical architecture offers beauty as the counterpart of justice with a shared parentage in the ideals of Nature. It is a humanist architecture with neither beauty nor justice available to us mortal humans in its completeness, but in our pursuit of happiness and our wellbeing we seek their fullest possible extent. This is the heart of the classical tradition running from ancient Greece and into our constitutional order. We the People formed our Constitution and the classical buildings we build to serve it within the classical tradition we formed from the experience of that history and the legacy of our mother country.

Nations on the Continent are direct if distant descendants of ancient Rome. Events unfolding there when our nation was being founded disrupted the traditional liaison between beauty and justice. Architecture left that union and joined the arts to serve pleasure, and beauty cut its ties to earlier philosophy and theories. Separated from Nature, it put beauty in the eye of the beholder and became a Fine or Beaux Art. Its buildings, while serving utility, were valued as visual objects with their purely formal properties tagged with a style name and connected historically to the Zeitgeist of the succession of unique ages or eras that produced them.

In 1789 came the fracture of classical architecture into styles with the style of ancient Republican Roman buildings commandeered to serve the liberal revolutionary Jacobins. The conservative, statist, revanchist regimes that quashed them used classical styles of French kings, and then exhausted and discredited themselves by conducting The Great War. Bubbling among the liberals had been alternative styles such as Jugendstil, Art Nouveau, and Liberty Style, and they became the seedbeds for the first vigorously anti-classical Modernists styles, most famously those of the Bauhaus and LeCorbusier. Both politically uncommitted, they were eager to serve the Nazis who preferred classical styles to promote their totalitarian tyrannical program, a choice that Modernists now use to discredit the classical style.

On our side of the Atlantic well into the 1930s the self-evident truths of Nature remained the basis of justice and of the beauty that classical architecture offered as its counterpart in federal buildings, except for the mid-19th century lapse into Romanticism. During the jazz-age 1920s architects began fashioning classical carcasses of private and public building with smooth surfaces and swooping curves, and the Modernism of the 1932 International Style exhibition seduced the avant-garde. In 1937 Harvard installed Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus education system, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe arrived in Chicago on the same mission. After the war Bauhaus instruction rapidly replaced classical instruction, and corporations, cultural institutions, and universities deployed Modernist style buildings as harbingers of a peaceful and prosperous future.

A fringe resisted: Henry Hope Reed tended classicism’s flame, Allan Greenberg used it, the University of Notre Dame and then a few others began teaching it again, and interest groups formed.

But in drab, gray Republican Washington in 1962 the New Frontiersmen installed Modernist styles in the nation’s builder, the GSA. Its Guiding Principles, supplemented in 1994, called for “an architectural style and form which …will reflect the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability of the American National Government” and draw on “the finest contemporary American architectural thought,” which was by then vigorously anti-classical.

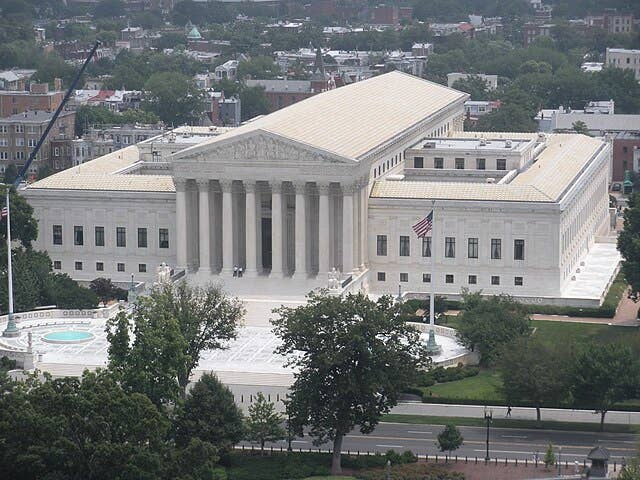

The resulting federal buildings lacked popular approval but were treated by the press and the profession as the face of liberal progressivism. In a time of intense partisanship and division the conservative reaction came on December 22, 2020, when an Executive Order (EO) by President Donald Trump condemned various Modernist styles, called some new federal buildings ugly, and ordered that classical architecture be preferred for new federal buildings. A draft leaked in February had used the term style quite liberally; the revised version avoided calling classicism a style but named “Neoclassical, Georgian, Federal, Greek Revival, Beaux-Arts, and Art Deco” as classical styles. “’Classical Architecture,’” it stated, “means the architectural tradition derived from the forms, principles, and vocabulary of the architecture of Greek and Roman antiquity, and as developed and expanded” by architects from Alberti to Delano and Aldrich. It declared that the new federal buildings, like those of “America’s beloved landmark buildings, [are to] uplift and beautify public spaces … command respect from the general public … [and] visually connect our contemporary Republic with the antecedents of democracy in classical antiquity.”

The profession and press, predictably, howled that this would “stifle” the evolution running from Jefferson to Kahn, discourage “freedom of expression,” and “slow the national and community pace of progress and innovation.” The EO said, “Design must flow from the architectural profession to the Government, and not vice versa,” but an opponent objected that this “inappropriately elevates the design tastes of a few federal appointees over the communities in which the buildings would be placed.” The EO had noted that architects are to “serve their clients, the American people” with buildings that present “beauty and visual embodiment of America’s ideals,” and called for a role for the public in selection of the architects and approval of design, anathemas to the profession.

The 1962 program installed by a minority fringe of liberal progressives dedicated to an architecture that was of its time and leading into the future; the later minority fringe of conservatives claimed popular support for restoring beautiful federal buildings to their traditional role and service. But by then beauty was residing in the eye of the beholder, and mere preference for tradition was a weak reed to lean on when public money is involved.

The Constitution protects private property from government’s intrusion except to assure protection of public health, safety, and general welfare, so it could not interfere with the stylistic preferences of corporations, institutions, and others spending private money except to protect public health, safety, and general welfare. It also protects freedom of speech with architecture as a form of speech, although that claim has not had a constitutional test.

Speech is a form of language that conveys content. If architecture speaks, what should the government have it say? The 1962 program would have it “provide visual testimony to the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability of the American Government.” In that mixed bag enterprise and vigor are about change and ring of the 1960s’ progressive partisans hurrying into the future. They belong to the world of style as fashion where a frock or a building is au courant one day and out of fashion the next. Dignity and stability? Not long ago Brutalist style buildings (many now crumbling) did so, and now they are a fringe taste among Modernist aficionados.

Modernism offers styles, but classical architecture is not a style. A style is a tag attached to a building that identifies the appearance of the taste preferred in a place at a time or by a person. The key word here is preferred; styles change as preferences change. Each new one makes its predecessor obsolete.

Styles claim no connection to justice or Nature, while classical architecture speaks of a tradition in which beauty is a visual counterpart to justice. Its most beautiful buildings are designed for service to the most important purposes, to exhibit the models for the order, harmony, and proportionality of beauty in Nature, and to stand as counterparts to the laws that serve the ideals of justice. The principle of decorum guides the models’ dilution to assure that the beauty is appropriate to the relative rank of the building’s purpose, the parallel to having the punishment of a law fit the crime and the offender.

While buildings and laws in the classical tradition embody the best appropriate form of Nature’s enduring and unchanging ideals of beauty and justice at the time they are instituted, they also have styles that act as tags of secondary attributes in providing visible evidence of when, where, and by whom they were made, from Greek to Art Deco. The styles change, but the primary content, the enduring and unchanging character of beauty as the counterpart of justice, their twin in Nature, remains.

The conservative fringe’s bill titled the “Beautifying Federal Civic Architecture Act” wants to continue traditional classical architecture as belonging to “the architectural tradition derived from the forms, principles, and vocabulary of the architecture of Greek and Roman antiquity; and later developed and expanded.” But how answer those who call Philip Johnson’s Postmodern AT&T Building (aka 550 Madison Avenue and formerly Sony Tower) classical?

Needed are criteria for defining the classical in architecture and for assessing beauty more objectively than mere as a preference made in the beholder’s eye. Can preference ever be a legitimate reason to commit public money to the construction of federal buildings? The New Frontiersmen and their successors have thought so, and many people do prefer Modernist style buildings, but Trump prefers classical federal buildings. This worthy program deserves better reasons.

To implement it the Republicans’ bill would establish a commission, but it is unlikely to be successful without a purge and replacement of the appointees it would include. The program was born in partisanship, but both sides in this fight want the same thing— buildings that serve and ennoble the nation and its people and displays the nation’s character. Needed is reasoned deliberation in determining how public money is used to serve federal programs. Architecture, like beauty and justice and all good public policies, has no party. Classical architecture, the only architecture suitable for the nation’s character, ought to be restored to serving the common good.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.