Carroll William Westfall

A Flawed Contributor to Classical Architecture

Fiske Kimball (1888-1955) promoted America’s classical architecture in his American Architecture from 1928 and now available online. Although it shortchanges architecture’s role in American life, the short book intended for a general audience can be read with pleasure and profit today.

Constantly focused on buildings and architects, it has few photographs but rich and precise characterizations of buildings. It tucks in information about materials and construction, stresses regional variations, tracks technical, economic, and social changes that architects surmounted, and covers the domestication of foreign imports.

The first six of its sixteen chapters survey what the earliest colonists brought from their various native lands and built in a country largely lacking models built by an aristocratic class.Architecture improved with wealth, settlement, and better models and more books, but “The ideal of the Colonial style remained: conformity to current English usage.” “Only with the founding of the Republic does a creative spirit appear, a new sense of form.”

The impetus was the Virginia Capitol that, quoting Jefferson, presented “a favorable opportunity for introducing into the State an example of architecture in the classic style of antiquity.” Long preceding anything similar abroad,

With the arrival of Greek detailing when “solidarity with ancient Greece … reached every department of life … Jefferson’s dream thus came true—to establish the classic as a national style.… [I]t furnished the basis for ingrained love of the simple, austere, refined and chastened in architecture which underlie the spirit of our creative work today.”

But as in all artistic creation, Kimball continues, the work of a new generation would undermine this moment of highest splendor. Romanticism arrived, favoring rustic landscapes while the struggle “between classic and Gothic,” and then a “confusion of tongues” in the “Battle of the Styles” brought on “What have been called the ‘Dark Ages’ of American architecture … in the mass of vulgarity.”

Architects were then also exploring the potential of new industrial materials and needs. Ruskin cried for “truth to construction,” and foreigners saw Richardson’s buildings as “rustic lodges of great boulders and image of what they thought architecture in a new continent ought to be.” Richard Morris Hunt, the first American from the École des Beaux Arts, adapted the châteaux of the Valois for America’s new wealthy class, and England’s William Morris and Normal Shaw made lesser housesmore English. But finally McKim, himself from the École, with his partners restored American vernacular while others explored other regionalisms and used improved skills in building Gothic and classical universities, churches, and other public buildings.

Chapter XI, titled “The Stages of Modernism,” addresses the new challenges of the modern era. Just as beauty was raising “again to independent being,” new ideas about science and nature threatened the received ideas about art, exalting “truth as the supreme principle, in art and in science.” The modern “idea of evolution, as the progressive adaptation of organic form to function and environment” entering ideas about architecture was “fundamentally hostile to every ‘revival’ of historical styles in the modern world” and undermined the “doctrine of truth in art, of obedience to nature.”

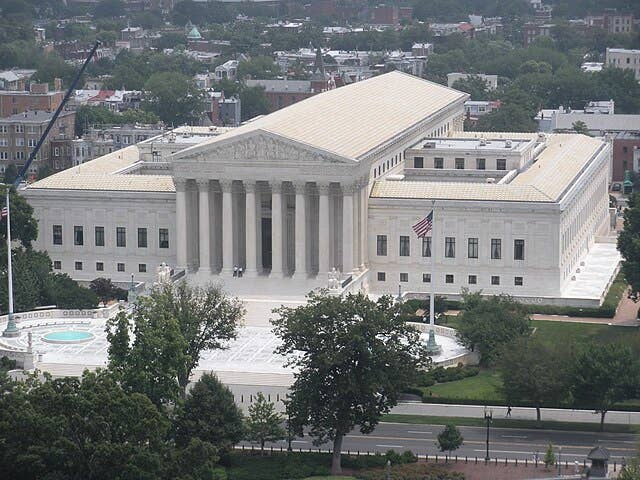

Nonetheless, despite romanticism’s debacle, American classicism was recovered by McKim as leader and Burnham asimpresario, at the Fair in Chicago in 1893, in the buildout of the 1901 McMillan Plan for Washington, and through the City Beautiful movement throughout the country. Kimball declared,“Their mature work was not merely a belated historical revival, … not merely imitative.” In it after a struggle, a “coherent body of tradition was again established,” perfectly embodied in the Lincoln Memorial.

Kimball reveled in this reestablishment as the restoration of tradition, but the classical was not the only style architects choose to restore, and other options that tradition offered entered the fray of an enlarged Battle of the Styles. Among them were styles validated by the modern understanding of nature that had replaced ancient Natural law whose ideals claimed eternal validity with laws of nature explaining temporal changes in nature’s material realm. Architecture was absorbing these, with the skyscraper as one outcome. Another was the style of Louis Sullivan who emphasized “the novel element in modern life, rather than its continuity with the past.” Here was “beauty through truth to nature, rather than abstract beauty through relations of form.”

Whether tradition, nature, or some other alluring basis for design, in this modern world architects were free to choose the path to follow. But no matter the choice, Kimball saw developments being swallowed by the maw that the style of an age follows the irreversible sequence of youth, maturity, and decline. After the Great War among the classicists the “freshness” waned, Sullivan’s formulae were generally dismissed, Eliel Saarinen’s promising “square tower with simple receding bastions” was bested by revivalism, and some architects welcomed the “creative liberty secured by the Germans,” but most retained “the larger unity of American modernism, toward the poles of which—functional expressiveness and abstract form—its masters have variously striven.”

Kimball’s engagement with architecture had largely shifted in 1925 when he began his thirty year directorship of the Philadelphia Museum, [figure 7] well before architects abandoned seeking beauty and let themselves become hapless captives of the Zeitgeist that demands that creativity be displayed in Modernism’s parade of styles. His doctoral dissertation was on Jefferson as architect, and in 1919 he had become head of the newly founded art and architecture department at the University of Virginia.

He designed a few buildings, [figures 3, 4, 5] and he began his long involvement in restoring Monticello, the basis for the 1935 Shack Mountain retreat he built nearby.

[figure 6] He left Virginia in 1923 to establish New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts allied with the Metropolitan Museum that, after 1937, became a premier center for history of art’s Germanic Kunstwissenschaft.

Kimball’s book avoided that German import’s reductionism that stresses styles as the marks of buildings as art objects of ever changing times. For Kimball, styles revealed architects’ inventive responses to changing circumstances, and classical architecture was a style immersed in time’s continuity. But here he misunderstood the classical in architecture. The classical is not a style, although classical buildings have styles that, like all buildings, document when, where, and by whom they were built. Classical architecture, unlike its styles, do not belong to time. Its building do, but their beauty and service to the common good place them outside time, in Nature, the repository of ideals that guide our pursuit of happiness in seeking to know the true, do the good and just, and make beautiful things. Our nation’s founders turned to Nature when they were “eager to throw off provincial dependence in matters other than that of sovereignty”to introduce a new age, one with a new constitutional order that enshrined “lawfulness and reasonableness.… Here was the relation to natural law [sic], one of Jefferson’s fundamental conceptions.”

Kimball was among those in his generation who conflated Natural law with the laws of nature that were rising to dominance in the modern age. Jefferson’s fundamental conception shared Nature with classical antiquity, with his mentor Palladio, and with the other founders. Its prominence in architecture was disrupted by romanticism and then reinstituted briefly before Modernism’s rise finally flummoxed it after World War II. Under Natural law’s regime the ideals that Nature holds take different forms or styles over time. The sights and sounds that the senses feed to the intellect to ponder are passed on to the soul or heart to satisfy the pursuit of happiness in the good and the beautiful; in the deracinated modern age, thesenses feed the sentiments with pleasure as adequate reward, with no role for the intellect and no interest in beauty or serving the common good. Change and style are satisfied, and asKimball noted, “What is modern for one generation is no longer modern for the next.”

Kimball wrote this book as a curator, not as a Kunstwissenschaft historian. Classical architects value what curators offer, while historians teach Modernists the styles that they must not use. Kimball’s successors at Virginia, Joseph Hudnut, said this about history in 1957. “[T]he teaching of architectural history has, or ought to have, only one important function: that of affording the students an experience of architecture and, especially, an experience of excellence in architecture.” Buildings, he averred, come from the “great spirits” who designed them.

Hudnut left Virginia for Columbia where, as dean in 1933, he began dismantling the Beaux Arts program before moving in 1936 to be dean of Harvard’s newly created Graduate School of Design. With even greater zeal he cleared out the “Hall of Casts,” removed those on the façade of McKim’s building, [figure 8] and moved out the library’s history books—they taught “archaeology” rather than architecture. And he hired Walter Gropius, who upped the ante, making history courses electives, promoting science and technology, and passing on no body of knowledge but instead cultivating each student’s instincts in the mandatory Bauhaus Vorkurs. This enabled them to contribute to the parade of Modernist styles that replaced the classical’s beneficial stream of beautiful variations serving the common good, a replacement that Kimball role for style facilitated.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.