The Forum

Statues In Urbanism

The statues where I grew up, in the North, were undemanding, and then, on the grounds of the Texas Capitol, for the first time I came face to face with Johnny Reb, and I felt deep revulsion.

I became inured to the Confederacy’s continued presence when living in Charlottesville. I could ignore the Johnny Reb outside the court house and the pair of generals in their own parks nearby in a city rich with statues. Five more were at the University, two Jeffersons, a Washington, the Blind Homer Guided by a Student (1907), and The Aviator. Two more along Main Street, with two local boys, William Clark astride his horse with his party of six, and Sacagawea showing the way to him and Meriwether Lewis. Lately the city has indulged the arts community by buying or accepting modernist works scattered about.

There are 47 or more outdoor sculptures in Richmond where I now live. An equestrian George Washington with six Founders and six virtues installed in 1850 to 1869 outside Jefferson’s Capitol is the star. Elsewhere Lincoln sits with his son Tad, and now various African Americans are found: Arthur Ash, the tennis champion; Maggie Walker, the entrepreneur; civil rights lawyer Oliver Hill, and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, with 14 figures and one cross memorializing men who served the Confederacy, eight of them as generals.

After the Charleston murders the Confederates’ presence has become an issue. In Charlottesville a murderous rally followed the city council’s decision to remove the equestrian statue of General Robert E. Lee dedicated in 1924 and rename his park Emancipation Park with General Jackson’s Freedom Park with his 1921 equestrian later voted for removal. Black plastic now shrouds the generals awaiting a court decision concerning the authority to remove them.

Elsewhere statues have tumbled, been removed or become subjected to intense debate. “Unite the Right” that sponsored Charlottesville’s rally cancelled one planned for Monument Avenue, Richmond’s Confederate Valhalla. The mayor had already formed a commission to determine how Richmond’s statues might be “contextualized.” Its first meeting came after the Charlottesville events, and was quite uncivil. Now the mayor and the governor favor removal, and the next meeting has been postponed. Meanwhile the Republican candidate for governor in November’s election advocates leaving them and claims that removing them would cost the city $3 million a year in tax revenue due to the district’s diminished real estate value. Preposterous, says his opposition.

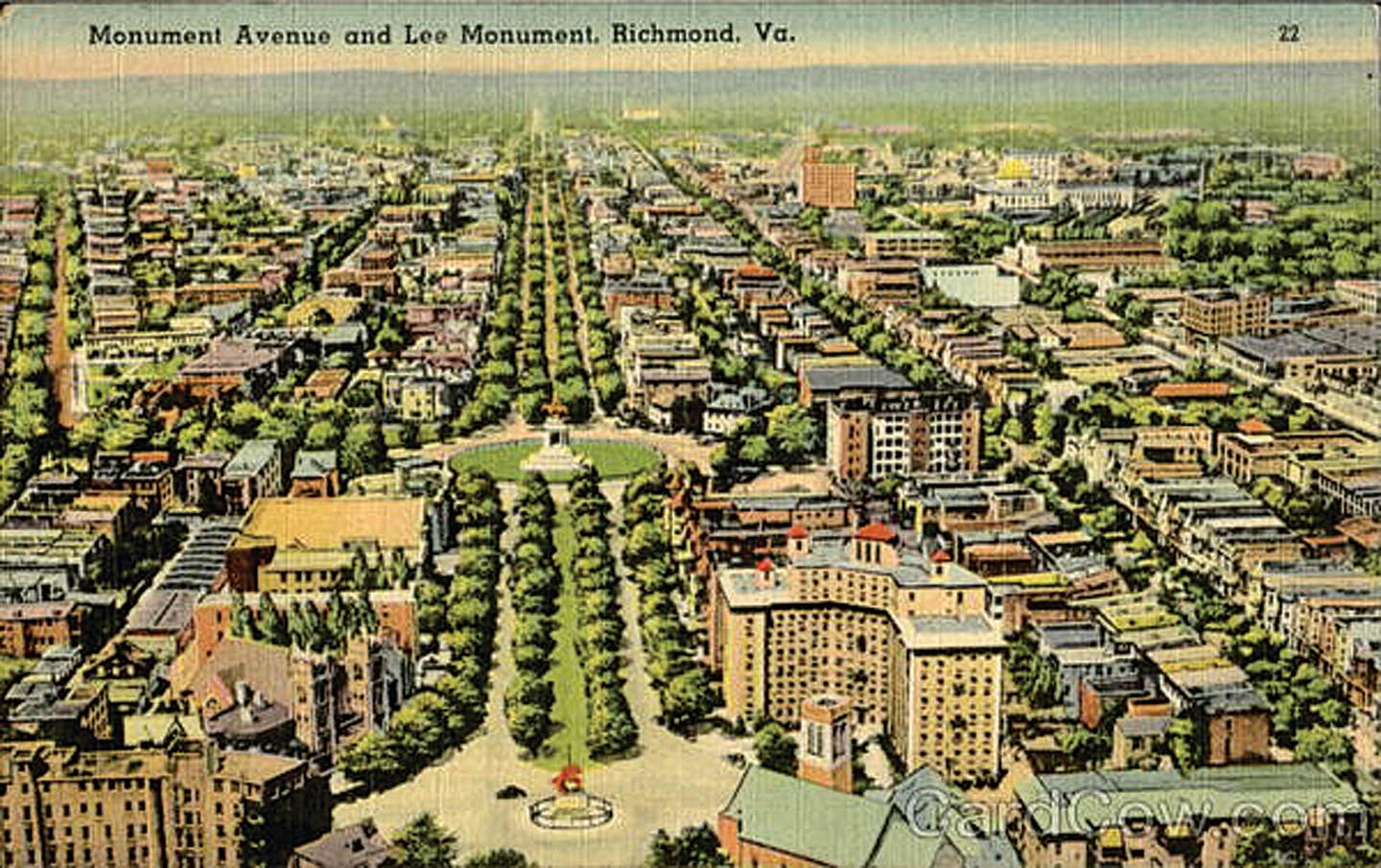

The statues’ role in urbanism intensified the issue. Lost Cause advocates seeking a statue of General Robert E. Lee found a place for it in 1887 in a real estate extension of the better residential district. In 1890 a massive Confederate assembly dedicated the statue in its 50-foot diameter reservation on the divided, treed boulevard. In 1907, the equestrian Jeb Stuart and the standing President Jefferson Davis were added, again attracting large assemblies, but fewer came for Stonewall Jackson on a horse (1919), and the last, Matthew Fontaine Maury in 1929 sitting behind the globe he had mapped.

In 1997 L. Douglas Wilder, the first African-American elected as a state’s governor, got the African American Arthur Ash placed on the Avenue, albeit near the county line.

Richmonders love Monument Avenue. On Easter ladies in their invented hats and dogs in costumes parade there, and paving over its noisy asphalt blocks has been blocked. But now, after the murder in Charlottesville, those Confederates, but not the others, are a major issue.

Raising Moral Issues

The debate’s intensity attests to urbanism’s role in raising moral issues at the heart of the civil life. Traditional buildings using conventional compositions adjusted to their present time and enmeshed in an ever-changing urbanism identify the purposes they serve in a good city. Statues and figural decoration give them voice clarifying the common good that facilitates each individual’s pursuit of happiness. The debates about those Confederates is about what that voice is saying now.

Some strident voices, thankfully few, want them to remain to inspire a continuing fight of the Lost Cause intended to restore the South’s status quo ante. Others want them kept lest history be edited and forgotten. There are calls to “contextualize” them, perhaps by hanging signs on them: “I did something bad.” A few denounce them as incorrigibles who ought to be banished and forgotten. The National Cathedral in Washington is removing Lee and Jackson from their stained glass window, and Richmond’s Saint Paul’s Episcopal where Lee and Davis worshipped is excising Confederate images and symbols, but not without controversy. Others would ostracize them to museums where, like altar pieces formerly in churches, their aesthetic qualities can be appreciated without engaging their content.

The argument for removal accepts the premise that urbanism is purely a matter of technical management and buildings are aesthetic objects or instruments serving the economy, but treating all those as tools cannot produce urbanism that hosts the good city, the one that facilitates the pursuit of happiness, where people live their lives in the present aware of the past and with hopes for the future.

I suggest that cities that have Confederate statues ought to leave them alone to serve as powerful reminders of a past wrong and add statues of inspiring examples of warriors who fought to right wrongs and urge us to fight the injustices in our present. Making these new statues as prominent as those of the survivors will shame the survivors and remind us not to stand still but to move forward without a backward thought.

Each local community needs to decide whom to add. Richmond’s candidates might be Sojourner Truth, Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Martin Luther King, Jr., Thurgood Marshall, L. Douglas Wilder, etc.

Adding them to the urban fabric will make a glorious American Valhalla and quash a problematic Southern display. Doing so as an act of civic good might forge a powerful unity within a divided community.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.