The Forum

Stop Skyscrapers in Paris

The world loves Paris because it is beautiful. Since the 17th century, first royal decrees and then statutes have governed its appearance. Paris has had height limits for hundreds of years, and they help maintain the city’s unique low skyline. But today political pressure is gutting the law. The beauty of Paris is under threat. Residents feel powerless. And the world does not know.

The zoning law of Paris, the Plan Local d’Urbanisme (PLU), aims “to preserve the urban forms and the patrimony coming from the history of Paris, all the while permitting contemporary architectural expression.” It specifies building heights and materials for facades, among much else. Permission may be refused if a building may “undermine the character” of its surroundings.

However, Paris City Hall, developers and star architects say that Paris needs skyscrapers to be modern, by which they seem to mean, more like Dubai. They accuse opponents of promoting a museum-city, a ville-musée. But opponents of skyscrapers, including French preservationist association SOS Paris and, more recently, the International Coalition for the Preservation of Paris, ICPP, which I founded, strongly disagree.

It doesn't have to be this way

It is not too late to stop the skyscrapers. To be sure, one skyscraper project, Renzo Piano’s courthouse, is complete, and ground has been broken for another, the so-called Duo. But dozens more are planned. To save Paris, we cannot rest.

Paris has not learned from its experience with skyscrapers. Height limits in Paris were relaxed in the 1960s and 70s, when modernists ran the planning department. One result was the universally-hated 210 meters (689-ft.) Tour Montparnasse, which disfigured the city in 1973. Parisians protested, and in 1977, the government re-introduced height regulations: 31 meters (102 ft.) in the center, 37 meters (121 ft.) on the periphery.

In 2008, ignoring the lesson of the Tour Montparnasse, and explicitly disregarding polls showing Parisians opposing skyscrapers, the City Council raised the height limits and approved construction of six skyscraper projects at the city’s gates. The then-mayor said elected officials must not be guided by polls, but by the general interest. He cited young families needing apartments, and he invoked the competition among world cities.

Today’s feverish, high-pressure, campaign for skyscrapers, however, looks more like power politics than like thoughtful policy. The media promote the campaign. The City of Paris gives architects exhibits in its 15 public museums, with attendant laudatory reviews, interviews, and conferences.

But excellent, indeed, conclusive, counter-arguments exist. Among them, that while France prides itself on aesthetic excellence, these skyscrapers are ugly. Following the French government’s order to vacate their recently-renovated historic buildings on the Ile de la Cité, the courts will move into the first of the new skyscrapers, Renzo Piano’s courthouse, in April. This banal 40-story-tall pile of glass boxes is a sock in the eye for all Parisians. Visible everywhere, it powerfully suggests the damage the entire range of the proposed skyscrapers will do when they encircle Paris.

Further, Paris does not need skyscrapers. Paris has a glut of empty office space and a shortage of housing, but the new buildings are chiefly for offices, and none is for housing. Today, according to 2017 statistics from A.T. Kearney, Paris is an alpha city of world commerce, with New York and London, so skyscrapers won’t boost its ranking. Experts say these skyscrapers can’t meet recommended local sustainability standards. And there is more.

In their feverish haste to build skyscrapers, the City of Paris and the national government have signed wasteful contracts. The courthouse contract, a public-private partnership between the national government and the developer Bouygues, requires the French government to pay rent of nearly three billion euros over 27 years, at a time when the Ministry of Justice is painfully short-funded. The lawyers opposing the move from the center of Paris showed the then-Minister of Justice, Christiane Taubira, that the contract was wasteful, and she, in turn, went to the Prime Minister, but the government insisted, regardless.

Most in contention today is the proposed 42-story, 180 meters (591 ft.) Tour Triangle of Herzog & de Meuron, a project of the developer Viparis. This ugly wedge of glass and steel has incited close re-votes in the City Council. From points on the Right Bank, it is smack in the line of sight of the 324 meters (1,063 ft.) Eiffel Tower. Arguing that this purportedly private development is actually a public project of Paris City Hall, and alleging favoritism in the award, disregard of legal procedures, and waste, SOS Paris has taken the matter to court, lodging civil and criminal complaints, still pending.

The courts, however, can also gut the PLU.

In 2001, the politically-powerful French conglomerate LVMH, the world’s largest luxury-goods company, bought the Samaritaine department store in the historic center of Paris. LVMH engaged the Japanese Pritzker-winning architecture firm SANAA. The art nouveau Samaritaine facade on the Seine is a nationally protected monument. The structures behind that building on the historic Rue de Rivoli, dating from the 17th through the 19th centuries, were protected only by the PLU. There, SANAA proposed a block-long undulating glass façade, opaque, seven stories tall, without doors or windows.

Challenging the demolition and building permits, arguing that the design violated the PLU, SOS Paris won in the Administrative Tribunal and then again on appeal. Political pressure was intense. The old buildings were demolished. The City and LVMH appealed to the highest administrative court in France, the Council of State (Conseil d’Etat). In 2015, it held for LVMH and City Hall. The deciding factor? The design was “contemporary.” That reasoning is contrary to the plain language of the PLU, but the judgment is final.

One must wonder what happened.

Paris is the world’s city. If the world knows what is going on, together we can stop the skyscrapers. That is the aim of the reports, book, and conferences that ICPP sponsors and of the lawsuits that SOS Paris brings. All for the sake of beautiful Paris. Please support us. Go to SaveParis.org for information.

About the author

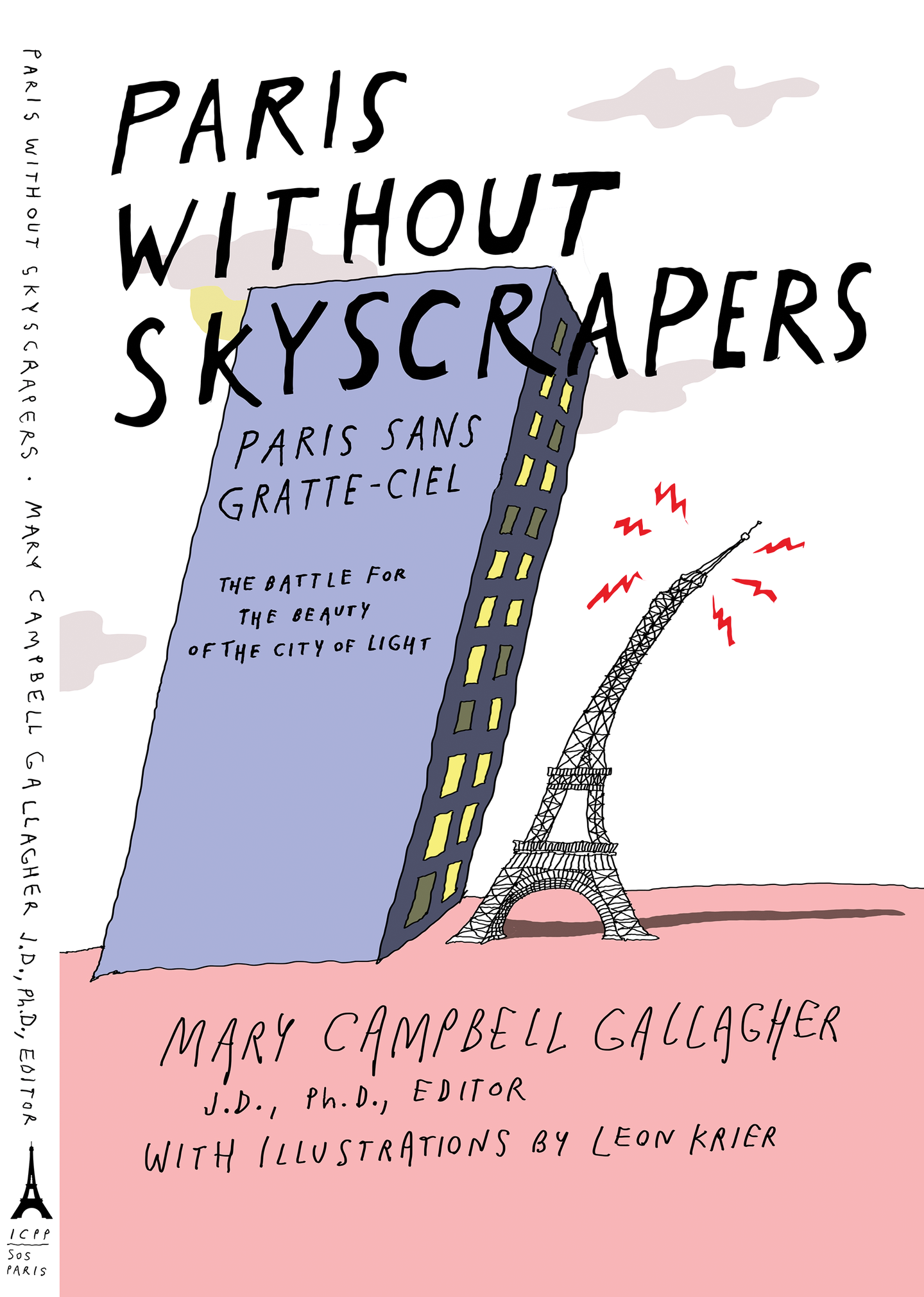

Mary Campbell Gallagher, J.D., Ph.D., is the founder and president of the International Coalition for the Preservation of Paris, ICPP. She is U.S. liaison for SOS Paris. She is editor of the forthcoming book of essays, Paris Without Skyscrapers: The Battle to Save the Beauty of the City of Light, coming from ICPP, in cooperation with SOS Paris. Gallagher is also president of New York-based legal training company BarWrite and BarWrite Press. She can be reached at mcg@marycampbellgallagher.com.