Patrick Webb

Natural Cement: An Oldie but a Goodie

Cement has unquestionably transformed the human experience and it could be argued is at least partly responsible for ushering in the modern, industrialized world.

The word cement has an interesting etymology of its own, going back to Roman times. The Latin word 'cæmenta' meant chips, specifically the hewn stone chips used together with mortar in rubble construction. The root verb 'cædere' means to chop or slay, precisely where we get the '-cide' suffix from, referring to something 'slain'. Nevertheless, the English word cement has come to mean the binder of the plaster, stucco or mortar rather than the 'chips' or aggregates it holds together.

What makes a cement “natural”? The natural designation indicates that the raw material, a type of limestone known as clayey marl is simply mined and burnt with no further additions. Portland and other “artificial” cements by contrast are produced from a man-made mixture of pure limestone, silicates and clays that resemble the chemical composition of marls or vary from them in a controlled, reproducible manner.

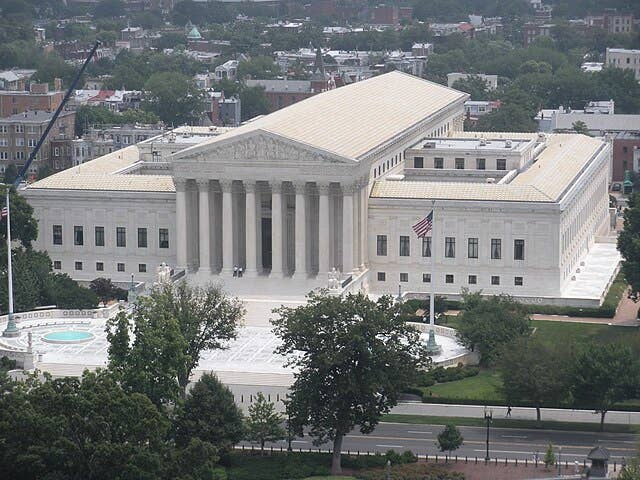

Natural cements first came into widespread manufacture and use in France and England but quickly spread to the United States. Many prominent national monuments and infrastructure projects utilized natural cement including the US Capitol, Washington Monument, Brooklyn Bridge and Erie Canal. Natural cement likewise saw widespread use in fine residences and commercial buildings as run-in-situ mouldings, cast ornament and smooth exterior stuccoes often scored with joints in imitation of ashlar stone.

Chemistry & Manufacture

Similar to the previously considered natural hydraulic limes, natural cement is derived from a limestone that contains specific impurities that have infiltrated deeply into the limestone over geologic time. However, whereas the limestones that produce natural hydraulic lime and natural cement both contain amorphous silica, what distinguishes those for natural cement is an appreciable infiltration of finely constituted alumina. These special natural cement producing limestones are known as clayey marls.

Due to the fine, intimate infiltration of silicates and alumina that have occurred naturally within the limestone, the marl can be burned slowly at a relatively low temperature of under 2200° F. This dissipates all of the CO2 from the limestone component of the marl. Some of the remaining “quicklime” or CaO fuses with the silica content creating belite, the calcium silicate compound responsible for the slow setting action with water of natural hydraulic limes. However, remaining quicklime also fuses with the alumina at these higher temperatures forming an entire family of calcium alumina compounds. The “clinker” or burnt materials are ground into a fine powder, the natural cement ready to be blended with aggregates and water.

These alumina reactions are what distinguish natural cements from hydraulic limes as the setting properties are completely transformed. Whereas pure lime must reabsorb CO2 from the air to slowly set over months and hydraulic limes will take from hours to days for their initial set with water, the hydraulic reaction of aluminates with water characteristic of natural cements is almost immediate, a matter of minutes. Although chemically distinct, natural cements share this property of rapidity of set with gypsum plasters. Likewise natural cements have very strong binding capacity giving them a much greater freedom in how much and what kind of aggregates are used than is possible with other limes.

Properties & Specifications

Fortunately, natural cement continues to be produced in the United States. Natural cements have an early compressive strength from the initial calcium aluminate set and low permeability. This makes them an ideal binder for mortars used for siliceous sandstones and other hard stones like granite. Because of the similar chemistry to natural hydraulic limes, they share a long term silicate curing pattern and are thus very compatible binders. As such natural cement is often used as an additive to natural hydraulic limes to speed up the set, increase compressive strength, improve erosion, salt and frost resistance, reduce shrinkage and decrease permeability.

Because of its widespread use from the 19th through the beginning of the 20th century, obviously there are many applications in historic restoration work. However, as there is an increasing appreciation for traditional craft means and methods in addition to traditional architectural forms, natural cement has many possibilities for new construction. Traditional plasterers who work with gypsum will feel very comfortable using natural cement to run mouldings in place as well as casting in ornament. As natural cements are largely self-binding, not exceedingly restrictive in the use of aggregates, rich mixes that achieve fine detail are easily achieved. In combination with natural hydraulic limes, natural cements can form the basis of durable and beautiful, integral colored exterior stuccoes.

In our next article we'll wrap up our consideration of the family of lime plaster with a look at the basis of 'Roman cement': Pozzalans.

My name is Patrick Webb, I’m a heritage and ornamental plasterer, an educator and an advocate for the specification of natural, historically utilized plasters: clay, lime, gypsum, hydraulic lime in contemporary architectural specification.

I was raised by a father in an Arts & Crafts tradition. Patrick Sr. learned the “decorative” arts of painting, plastering and wall covering as a young man in England. Raising me equated to teaching through working. All of life’s important lessons were considered ones that could be learned from the mediums of tradition and craft. I found myself most drawn to plastering as I considered it the richest of the three aforementioned trades for artistic expression.

This strong paternal influence was tempered by my grandmother, Geraldine Webb, a cultured, traveled, well-educated woman, fluent in several languages. She made a point of instructing her young grandson in Spanish, French, formal etiquette and opened up an entire worldview of history and culture.

After three years attending the University of Texas’ civil engineering program with a focus on mineral compositions, I departed, taking a vow of poverty, living as a religious aesthetic for a period of seven years. This time was devoted to clear reasoning, linguistic studies, examination of world religions, exploration of ethics and aesthetics. It acted as a circuitous path leading back to traditional craft, now imbued with a deeper understanding of interconnection in time and place. I ceased to see craft as simply work or labor for daily bread but among the sacred outward expressions of the divine anifest

within us.

From that time going forward there have been numerous interesting experiences. Among them study of plastering traditions under true masters here in the US as well as in England, Germany, France, Italy and Morocco. Projects have included such high expressions of plasterwork as mouldings, ornament, buon fresco, stuc pierre, sgraffito and tadelakt.

I’ve been privileged to teach for the American College of the Building Arts in Charleston, SC, where I currently reside and for the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art across the US. “Sharing is caring” – such a corny cliché but so true. I hardly know a

thing that hasn’t been practically served to me on a platter. I’m grateful first of all, but now that I might actually know a few things, it becomes my responsibility to be generous as well.