Clem Labine

McKim’s Penn Station Can Rise Again

A plan of jaw-dropping daring and imagination was recently unveiled at the symposium gathered in Philadelphia to assess the legacy of Henry Hope Reed (1915-2013), founder of Classical America. Reed spent a lifetime railing against the rapid obliteration of beauty in American cities caused by the Modern Movement; one of the greatest disasters being the demolition of Penn Station in 1963. The symposium audience was therefore delighted when architect Richard Cameron of Atelier & Co. outlined a project that would have brought a smile to Henry’s face: rebuilding Charles Follen McKim’s Pennsylvania Station. .

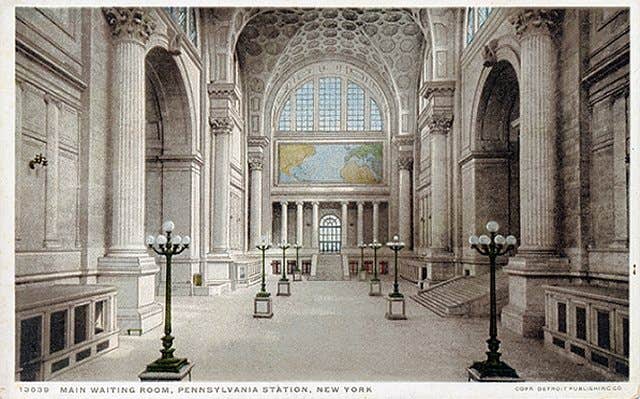

McKim’s original Beaux-Arts masterpiece was built between 1901 and 1910, inspired by the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. The classical edifice was a stunning achievement of both engineering and aesthetics: Its steel frame sheathed in pink granite and travertine, with 84 Doric columns and lofty halls with 150-ft. coffered ceilings, created one of the largest covered public spaces in the world. Built totally with funds from the Pennsylvania Railroad under the guidance of its visionary president, Alexander Cassatt, the privately owned building was more than a train terminal: It was also a gift to the entire city of New York. Rich in classical architectural detail and built of high-quality stone, the building set a standard for excellence in civic spaces. It was an awe-inspiring public realm where the poorest citizen could feel like nobility.

The demise and demolition of Penn Station

Alas, this privately sponsored public benefaction was too good to last. With the advent of jet travel after WWII, the Pennsylvania Railroad fell on hard times – and the lure of rising Manhattan real estate prices was too great to resist. The railroad sold the air rights above its underground track system, and McKim’s masterwork was demolished in 1963 – just 53 years after its opening. Rising in its place was the new home of Madison Square Garden – housed in a structure that’s a pedestrian pastiche of Modernist banalities (to put it kindly). The 650,000 travelers who use Penn Station daily are left to thread their way through a confusing dingy warren of underground passageways that now burrow beneath Madison Square Garden.

Everyone agrees the current situation is a scandal. New York’s Municipal Art Society recently sponsored a “design challenge” and invited four architectural firms to envision a new Penn Station. Predictably, only Modernist firms were invited to submit – with equally predictable results. (Creating beauty in the urban environment was not a requirement.)

Is resurrection in the cards for Penn Station?

Given that background, it’s easy to understand why the symposium audience was so excited by Cameron’s assertion that is it technically and economically feasible to rebuild a beautiful Beaux-Arts Penn Station similar to McKim’s. The architecture and construction are the easy part: The McKim Mead & White drawings still exist, and bringing them up to modern code and functional requirements would not be difficult. .

Cameron has also done considerable research with developers and real estate experts and is convinced that the air rights involved make the project economically feasible. The current disgrace that is Penn Station could be transformed into a beacon of civic beauty once again.

The biggest obstacles to any new Penn Station project are the Byzantine politics that always surround major real estate efforts in New York City. For one thing, the Dolan family that holds the short lease for Madison Square Garden has no desire to move. Political will is what’s needed to get a new Penn Station on track; nothing will happen until the Mayor and the Governor get together and crack heads. It will be a beautiful day in the city if and when that happens.

Clem Labine is the founder of Old-House Journal, Clem Labine’s Traditional Building, and Clem Labine’s Period Homes. His interest in preservation stemmed from his purchase and restoration of an 1883 brownstone in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn, NY.

Labine has received numerous awards, including awards from The Preservation League of New York State, the Arthur Ross Award from Classical America and The Harley J. McKee Award from the Association for Preservation Technology (APT). He has also received awards from such organizations as The National Trust for Historic Preservation, The Victorian Society, New York State Historic Preservation Office, The Brooklyn Brownstone Conference, The Municipal Art Society, and the Historic House Association. He was a founding board member of the Institute of Classical Architecture and served in an active capacity on the board until 2005, when he moved to board emeritus status. A chemical engineer from Yale, Labine held a variety of editorial and marketing positions at McGraw-Hill before leaving in 1972 to pursue his interest in preservation.