Carroll William Westfall

The Ground Under Our Feet

The ground under our feet is the land we build our urbanism on, and we mold it to serve the purposes of our civil order. Our civil institutions were developed slowly across more than four centuries, and so too was our landscape. It is intended to serve a free, self-governing people. Today it has difficulty doing so.

The early colonists saw wilderness when they landed in 1607 on the James River. James I’s charter looked for the “speedy accomplishemente of … plantacion and habitacion … digg, mine and searche for all manner of mines of goulde, silver and copper,” and bring the existing inhabitants “the true knoweledge and worshippe of God and … to a setled and quiet govermente.” The digging proved fruitless, but not tobacco cultivation.

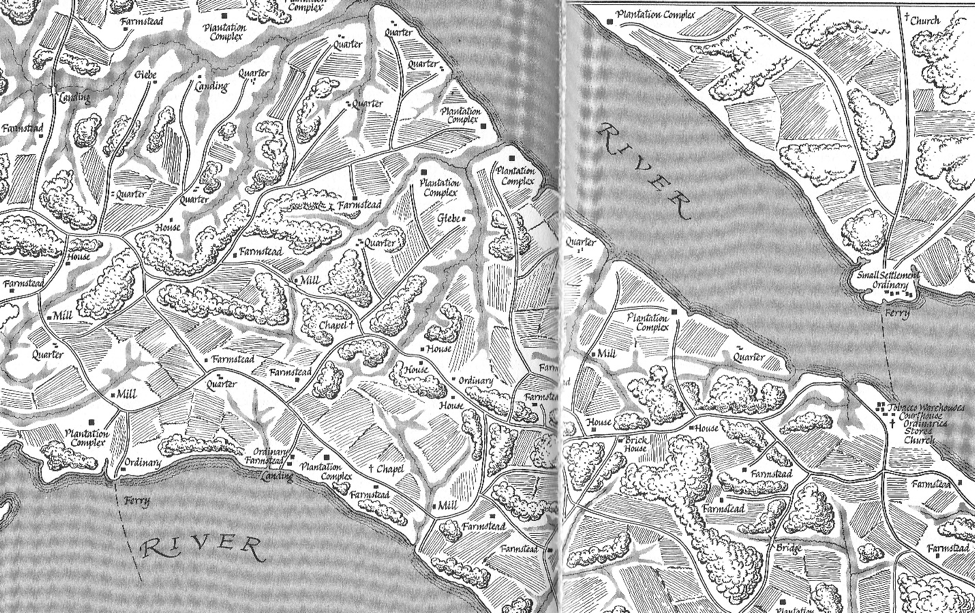

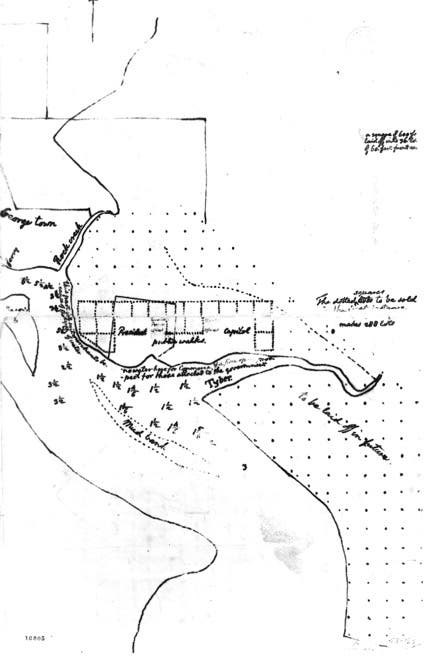

Colonists received land in proportion to the number of free, indentured, and enslaved workers they had to work it. In converting wilderness to a civil landscape they followed English patterns and built a dispersed landscape of large and small plantations organized into contiguous politically entities. (Figure 1) Those that had a courthouse were cities, then shires, and eventually counties; early ones such as one from 1619 could acquire the anomalous name Charles Cittie County. Its courthouse sits at a crossroads with no towns or cities but with several well-known 18th-century James River plantation houses (Berkeley, Westover, Shirley).

Cities with independent jurisdiction would be incorporated in the 19th century. Today when you drive west from the City of Richmond (population 227,032) you enter Henrico County (population 326,501), and leaving it you enter Goochland County (population 22,668); neither of those nor the other two collar counties have an incorporated town or city. Metro Richmond has 1,271,330 people.

The earliest New England colonists built surrogates for the Ark and the Church serving as earthly waystations on the road to Paradise. (Figure 2) After the first parent’s expulsion Enoch built Enoch, the first city, “East of Eden” where his descendants learned how to fend for themselves in the world and began “to call on the name of the lord.” But his brother Seth fathered the line leading to Noah whose Ark and the Church foreshadows the New Englanders’ “Citty upon a Hill, the eies of all people are uppon us.”

They filled the land with contiguous towns and cities, political entities that were later gathered into units called counties for administering the state’s laws. Today when you drive west and leave the Town of Amherst (population 22,668), incorporated in 1759, you cross Hadley (5,250), a town in 1661, and then reach Northampton (population 28,483) seven miles away, a town in 1653 and city in 1883, all three in Hampshire County (population 158,080 with a total of 19 towns and one city), which you didn’t touch but never left.

Surrogate wilderness survives in “rustic” city parks and vast reservations under sometimes fitful government protection. The states have jurisdiction over the rest of the land, and while different states have different legal traditions they use a common nomenclature learned from the ancient Romans including rural, urban, garden, and civil or city. The landscape itself more closely resembles England than the Continental landscape left from ancient Roman parceling.

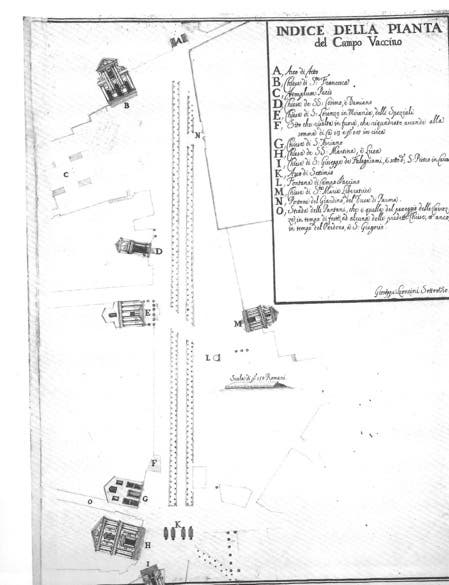

An ancient city was built as a refuge from chaos. Religious practices laid out the protective walls, subdivided the urban interior, and divided the surrounding land beyond the walls where the civil authorities exercised the laws in a rural agricultural landscape. Today when we see any growing thing in Rome’s Piazza di San Pietro it is a weed, not a cultivar, while the powerful Romans express their authority by cultivating luxuriant gardens within the privacy of their residential compounds. (Figure 3)

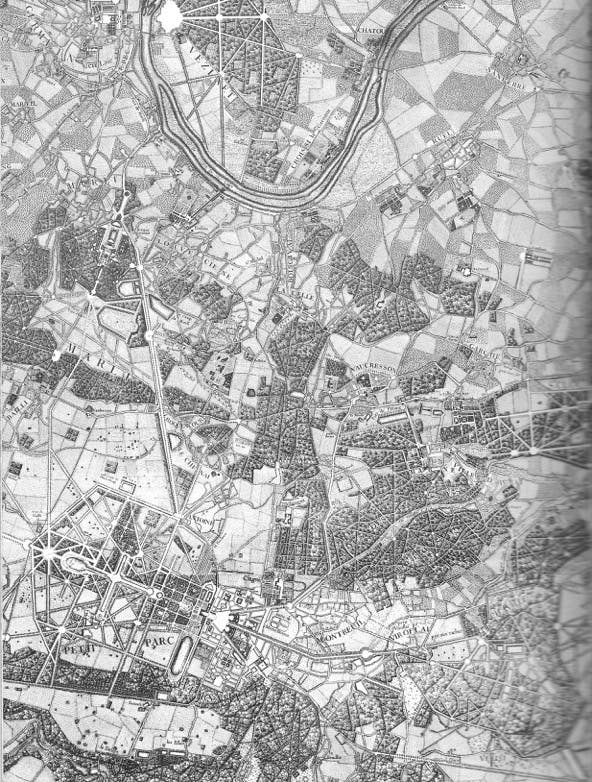

The strict separation of urban and rural began to dissolve when the Continental potentates tightened and centralized their autocracy over the countryside. To enhance papal and Roman dignity Pope Alexander VII (1655-67) brought extramural trees into Rome to stand in evenly spaced lines across the ancient Forum and along a few streets. (Figure 4) Louis XIV soon outdid him by urbanizing France. (Figure 5) He defortified cities and moved the realm’s defenses out to its octagonal boundaries, he planted rows of trees to shade his armies traversing his geometric web of streets that focused on his new seat of government at Versailles, and he converted Paris’ defensive walls into tree-lined boulevards.

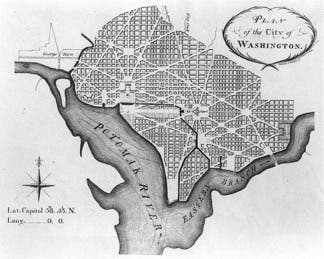

The world’s rural and urban ratio and the ratio of agricultural and industrial employment began their dramatic reversal even as the new nation was being founded. Jefferson, the Virginia slaveholding aristocrat, wrote, “Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever He had a chosen people, whose breasts He has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue.” No friend of big cities, when he assisted in designing the national capital he sketched an enlarged, gridded market town with sites reserved for the executive mansion and capitol and a “public walk” between them. (Figure 6)

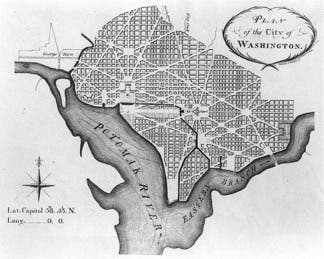

“The mobs of great cities add just so much to the support of pure government, as sores do to the strength of the human body.” Charles Peter L’Enfant, a familiar of Alexander Hamilton whom the President picked as designer mapped a grand city suitable for bankers and traders both gridded and with diagonal boulevards. (Figure 7)

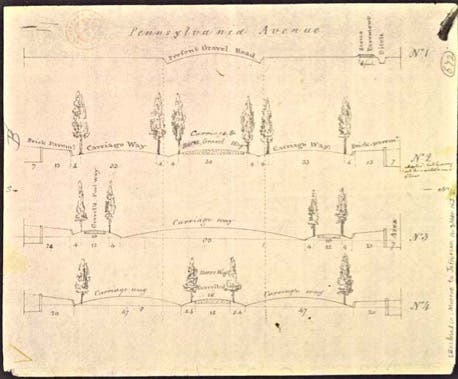

Jefferson, perhaps recalling Louis XIV’s streets, suggested lining Pennsylvania Avenue that connected the President and the Congress with carefully placed trees to stress the people’s role in the nation’s government. (Figure 8) For cities and the buildings placed on the land he favored classical restraint and simplicity, but Romanticism’s image of a restless, ever-changing, nature that enriched the soul quickly spread like kudzu as brambles, thickets, boskets, and other surrogates for wilderness entered the planners’ handbooks and exotic foreign styles showed up in architects’ sketchbooks.

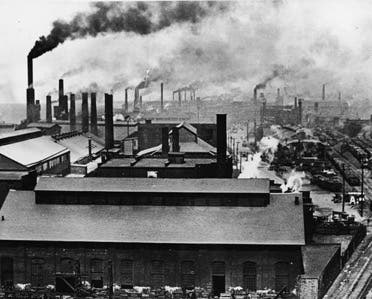

Americans redoubled their efforts to “digg, mine and searche for all manner of mines of goulde, silver and copper” with little regard for the debris they left behind in the urban, rural, and wilderness landscapes. (Figures 9A, 9B)

They mistreated the land, unrestrained by the dispersed political orders in homesteads, hamlets, towns, cities, and impressive metropolitan areas. None of these had the interest or the moxie to protect the “peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue” in the breast of every citizen and seek justice first.

In many states, cities quit expanding by pushing into counties; instead, rural tracts were invaded by a suburban fringe built by financial forces uninterested in producing an urbanism where citizens can pursue their common good while these and other forces worked at building city centers with disregard for the common good for all. Meanwhile between center and fringe a disruptive landscape was built with commercial buildings strung along wide roadways with green things occasionally sprinkled in blacktop parking areas and “office parks” with buildings, some even holding important government offices, in well-tended ameliorative vegetation inhibiting public access. (Figure 10)

In an earlier day the landscape’s land had a greater presence and role in our lives. Consider the National Park Service’s presentation of the rural courthouse in Appomattox when Lee surrendered to Grant and in the street where the Springfield lawyer Abraham Lincoln lived. Both sites leave it to us to supply the animals’ deposits and mud in the streets and kitchen gardens and more animals in the yards. (Figures 11A, 11B, 12)

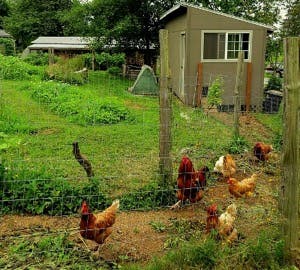

Today we ignore the rich landscape opportunities in the traditional American transect. Tom Low recently wrote about planting suburban yards as kitchen gardens. We don’t build the allotment and communal gardens that are common in Europe and recently on the White House grounds. Chickens, anyone? (Figures 13A, 13B, 13C)

Apartment buildings need not be impoverished; even simple plantings help. (Figure 14) Pots on balconies and along sidewalks can host plants. Sidewalks can have more than trees in their root boxes. A street can be made special with arboreal medians. (Figure 15A, 15B)

And why don’t we pay more attention to the landscaped settings of institutional buildings (schools, libraries, city halls, courthouses) and public parks large and small? It’s very American to do so.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.