David Brussat

Kismet, But Not in Mecca

With an apparent civil war under way within the Saudi royal family, the kingdom and its capital Riyadh are in the news again. But what about Mecca, where so many Muslims around the world travel on pilgrimage, maybe only once in their lifetime. What do they expect to find there?

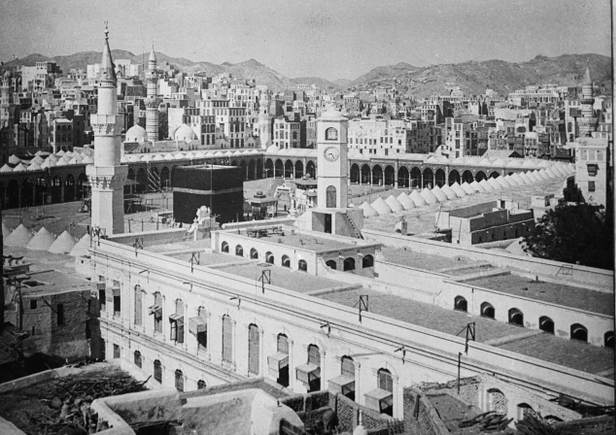

A New York Times piece, “The Destruction of Mecca,” by Ziauddin Sardar, author of Mecca: The Sacred City, opens by describing how Malcolm X visited Mecca in 1964 and found that it looked “as ancient as time itself.” Sardar adds: “Fifty years on, no one could possibly describe Mecca as ancient, or associate beauty with Islam’s holiest city. Pilgrims performing the hajj [in 2018, Aug. 19-24] will search in vain for Mecca’s history.”

Sardar describes how the historic center has been pulled down since the 1970s and replaced by what the world knows all too well: “It is part of a mammoth development of skyscrapers that includes luxury shopping malls and hotels catering to the superrich. … The city is now surrounded by the brutalism of rectangular steel and concrete structures — an amalgam of Disneyland and Las Vegas.”

The sacred places of Mecca have not been preserved. “Innumerable ancient buildings, including the Bilal mosque, dating from the time of the Prophet Muhammad, were bulldozed. The old Ottoman houses, with their elegant mashrabiyas — latticework windows — and elaborately carved doors, were replaced with hideous modern ones. Within a few years, Mecca was transformed into a ‘modern’ city with large multi-lane roads, spaghetti junctions, gaudy hotels and shopping malls. The few remaining buildings and sites of religious and cultural significance were erased more recently.”

This was not, at least not on its face, an example of Western neo-colonialism and its handmaids, the modern architects, stomping on the culture of yet another supposedly independent nation. Sardar blames the Saudi royal family and its leading clerics: They “have a deep hatred of history. They want everything to look brand-new.” These are the Islamic fundamentalists?

Let’s go back a decade and more to recollect that one of the sources of anger that drove Mohammed Atta to pilot a hijacked airliner into the World Trade Center was his hatred of modern architecture. We may be driven by Sardar's article to wonder whether Atta should have flown not into Manhattan but Mecca.

Sardar describes how the eradication of Mecca’s historic character has coincided with the transformation of the hajj, or pilgrimage, from a profound ritual into a shopping spree. I exaggerate, but not by much. Now that the “spiritual heart of Islam is an ultramodern, monolithic enclave, where difference is not tolerated, history has no meaning, and consumerism is paramount,” he writes, it should be no surprise that “murderous interpretations of Islam … have become so dominant in Muslim lands.”

It is easy, and proper, to blame this on Muslims and their leaders, but why does a supposedly fundamentalist society harbor such a “hatred of history” and “want everything to look brand-new”?

Something does not jibe here, and it is fair to ask how much blame should be laid at the doorstep (if you can find it) of modern architecture. Its practitioners have no problem building the instruments of the totalitarian state for tyrants. Witness China’s propaganda headquarters in Beijing, the CCTV tower, designed by starchitect Rem Koolhaas to look as if it were literally stomping on the people. The late Zaha Hadid designed a soccer stadium that looks like a vagina in a nation where women cannot show their faces in public.

This penchant for cultural violence goes back at least to founding modernist Le Corbusier’s proposed demolition of central Paris. He proposed the same for Algiers while working for the Nazis of Vichy, France. Backed by Goebbels, founding modernist Ludwig Mies van der Rohe tried to get Hitler to embrace modernism as the design template for the Third Reich.

Mies, Walter Gropius and other early modernists fled the Nazis, were handed architecture plum jobs in America, and used their new power to eradicate the culture of tradition from architectural education, then from architectural practice itself. Philip Johnson, an American Nazi in the 1930s who tagged along on Hitler’s invasion of Poland in 1939, led the reinvention of modernism as the brand for a capitalism increasingly estranged from the free market, with privacy on the wane and a sterility of place imposed by our increasingly statist society. The result is for all to see.

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.