Features

Christopher Alexander Wins Vincent Scully Award

By Michael Mehaffy

It was an unfortunate turn of events that the honoree for the 11th annual Vincent Scully Prize was suffering from a bout of pneumonia, and therefore unable to attend the presentation of the award at the National Building Museum in Washington, DC, in November. But that didn’t stop Christopher Alexander, author of A Pattern Language, The Nature of Order and other classics, from sending a message through his colleague Randy Schmidt – and even presenting some new work – at the awards program. In a fascinating address accompanied by several hundred images, Alexander offered tantalizing clues about new developments in his earlier, highly influential work on pattern languages.

The evening was to echo those two themes many times: the broad influence and scope of Alexander’s work, and the promising opportunities for further development that remain. Vincent Scully, the noted critic for whom the prize was named, praised Alexander as “a major pioneer in the revival of a humane architecture and urbanism that has been taking place over the past 40 years.” He observed that during the 1960s and ’70s, when most architects were preoccupied with individual buildings, Alexander was concerned with “patterns of the man -made environment as a whole, and with their relation to the natural world.”

Alexander’s pioneering work on sustainability was discussed by a panel that included Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, founding principal of Duany Plater-Zyberk and dean of the University of Miami School of Architecture, Witold Rybczynski, Martin & Margy Meyerson professor of urbanism and professor of real estate, University of Pennsylvania, Michael Mehaffy, past director of education, Prince’s Charitable Trust and research associate at the Center for Environmental Structure. The moderator was Robert Campbell, architecture critic for the Boston Globe.

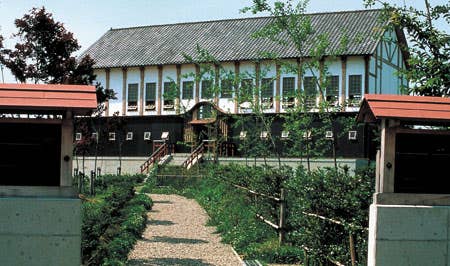

Plater-Zyberk noted that Alexander’s work “was always about being organic, responding to daylight, local materials, following the culture and so on. But if you think about it, his idea that you make places that people appreciate, people love, might be the formula for the ultimate sustainability.” Campbell and Rybczynski discussed Alexander’s many buildings around the world. Campbell pointed out that Alexander has built more than 300 buildings and asked: “Why aren’t they better known? Why aren’t they published in the magazines?”

Plater-Zyberk responded that they “have been published, and they are global, but I think when you look at them closely you will find that they are individually of their place.” That may mean they don’t translate well to magazine photos. “But I’ve always thought they were interesting because of the way they were made, which was always collaboratively, and by hand,” she said.

Rybczynski compared Alexander to the urban scholar Jane Jacobs. “I think there’s a sense in which both of them see the world as very, very messy, and they see the charm in that. And they’re on the one hand looking for order, but also at the same time very worried that too much order will lose the thing that you actually value.” This is what Rybczynski thinks gives Alexander’s buildings their remarkable qualities. “I think those beautiful hand-painted decorations that he slops on do that – they really make the building unprecious, and really quite wonderful.”

Plater-Zyberk believes Alexander’s troubled relationship with conventional architects and academics may be one of the most important aspects of his legacy. “Chris’ scholarship in fact has been his criticism, by his proposals, implicating and critiquing contemporary practice.” She noted that he was a major influence when founding New Urbanism with her partner, Andrés Duany: “It gave us courage to buck the dominant professional and academic trends, the inclination to focus beyond the individual building, on place making that might, in fact, please its users – a kind of radical idea.”

Alexander’s influence also extends to developers, she said, noting that at the Congress for the New Urbanism in Philadelphia, his keynote address actually “brought developers in the audience to tears.” She attributes this reaction to “his ability to speak to history, fact, and the very deep emotions in taking actions. He was calling for the kinds of reasons for which people make themselves developers, but in fact can never speak about in public.”

A Renaissance Man

Campbell described Alexander’s interest in painting, architecture, building, mathematics and other fields, and found it remarkable “how broad this person is – there seems to be a limitless number of topics we can bring up.” He was particularly intrigued by Alexander’s influence on computer science. A presentation earlier in the evening had documented how Alexander’s ideas had been used to develop the software that is now used in all iPhone apps, the Mac computer system, and many computer games. His ideas also led directly to the creation of Wiki and Wikipedia.

Campbell agreed that Alexander “has had an enormous, critical influence on my life and work, and I think that’s true of a whole generation of people.” He related how, early on in his education at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, he was profoundly influenced by Alexander’s landmark 1964 paper, “A City is not a Tree.” “It really blew away what were the foundational principles of the education at Harvard in those days, and it established in me an interest in actually looking at the world,” he said. “And not looking at a set of preconceived abstract mechanical ideas that were supposed to replace the existing world.”

For Rybczynski, the architectural books will remain Alexander’s most important legacy: “Those books are just a wonderful kind of connection that you feel you have with this person. They are, of course, theoretical, but they are written in a way which is very much alive.”

David M. Schwarz, of David M. Schwarz Architects, and chair of the Scully Prize jury, also pointed to Alexander’s enduring legacy: “He really has changed the way a couple of generations have looked at the built environment, and had a very profound impact on the discussion that people have about the built environment.”

This discussion is especially critical now, he said, because “the West is a model for development, and we owe it to the rest of the world to discuss how to develop – because so many people look to us.” TB

To see a video of the Scully Prize presentation and panel discussion, go tohttp://www.nbm.org/media/video/christopher-alexander.html

Michael Mehaffy is a collaborator with Alexander at the Center for Environmental Structure, and an author and consultant in sustainable urban development.