Features

Restoring Dignity in Transit: The Case for a Classical Penn Station Revival

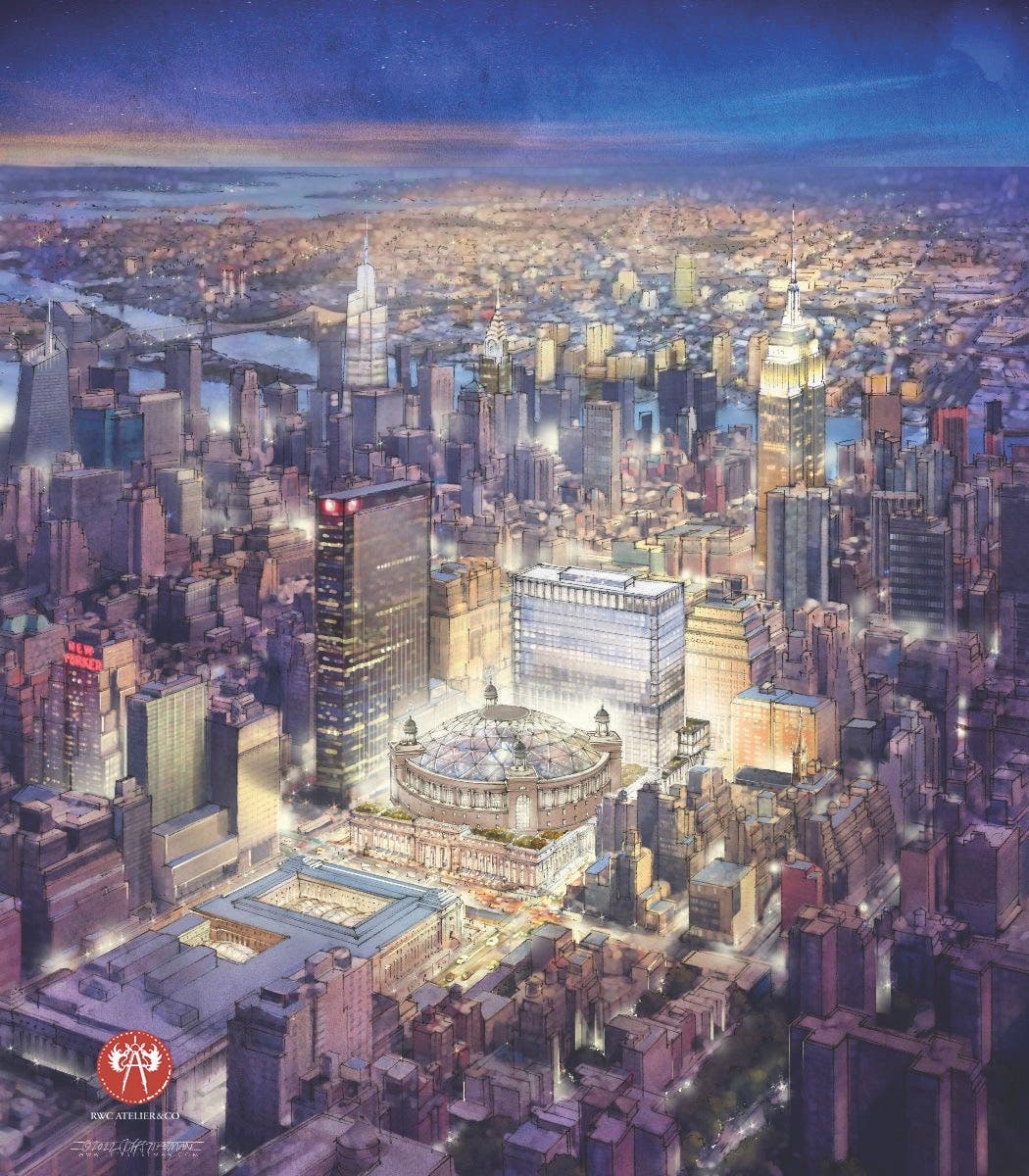

Renderings by Richard Cameron | Illustrative renderings by Jeff Stikeman | Digital renderings by Nova Concepts

What kind of world do we want to live in? What should our cities look like? Do we want – do we deserve – architectural grandeur to enhance the public realm and ennoble our daily lives?

Richard Cameron’s proposals for a new Pennsylvania Station – three variations on the theme of Charles McKim’s original edifice – answer these questions unambiguously. The architect says, in effect, let’s build what we truly want, create the greatest possible value for our city, and put paid to the abject built mediocrity that has been our lot for too long.

Every day, some 600,000 people pass through this civic embarrassment of labyrinthine corridors, crowded platforms, and graceless spaces. Vincent Scully’s oft-repeated observation that at Charles McKim’s Pennsylvania Station “one entered the city like a god,” whereas “one scuttles in now like a rat,” has to be multiplied by the dismal, daily experiences of 600,000 travelers through one of the world’s busiest rail hubs. Clearly Penn Station is worse than just a banal public building; it remains a perpetual trial for all who pass through it and a blot on their experience of our city and region.

Historical images of Penn Station, Detroit Publishing Co/Library of Congress

In the collective memory of New York, the Pennsylvania Station was widely seen as the grandest building in the city; many saw it as the finest building ever erected on American shores. Built for the Pennsylvania Railroad in the first decade of the 20th Century by McKim, Mead and White, the station was designed to be the capstone of a monumental infrastructure project consisting of two tunnels under the Hudson and East Rivers and the enormous Hell Gate Bridge. Thus, the PRR created what is now known as the Northeast Corridor linking New England to the American South and running straight through New York. The monumental importance of these undertakings for logistics and connectivity required a proportional civic gesture in the public realm, which is precisely what the PRR delivered, courtesy of Charles McKim, in the form of the Pennsylvania Station.

New Yorkers were awestruck at the station’s official opening in 1910. They entered through the building’s grand Seventh Avenue façade inspired by Bernini’s colonnade for St. Peter’s Square in Rome, processed through a grand series of spaces redolent of the Roman imperial Baths of Caracalla, and ended up in McKim’s vaulted glass and steel concourse–a grand synthesis of industry and classical grandeur. The exterior Doric colonnades were built of solid Milford granite while travertine quarried in Tivoli near Rome lined the interiors. The classical vocabulary was no random choice–it was integral to the image and identity of New York as it emerged as a world-class city. A more fitting gift to the city could not have been conceived. Its demolition a mere 53 years later was an appalling act of vandalism.

Governor Hochul recently promised us a Penn Station as “magnificent” as the Moynihan Train Hall across Eighth Avenue. She is open to architectural proposals beyond those put forward by the Metropolitan Transit Authority that could “compete” to bring about a “world-class masterpiece.” President Trump told her he wants a “beautiful Penn Station” in his initial phone call to her shortly after his election.

New York-based architect Richard Cameron’s answer to all this is to reconstruct the original Pennsylvania Station. While this might sound far-fetched today, any substantial alteration to the current Penn Station and its adjacent structures (Madison Square Garden and Two Pennsylvania Plaza) would cost multi-billions of dollars and take the greater part of a decade to complete. That truth applies to all current official plans and proposals – making Cameron’s vision more practicable and cost-effective than it may appear at first blush. We think the public deserves that the Cameron proposal and the others not submitted by the MTA—such as those of ASTM and the Grand Penn Community Alliance—be able to participate in an RFP or design competition for a revamped Penn Station.

Facilitating reconstruction of McKim’s masterpiece is the fact that the original station’s footprint and column grid are still intact. After all, it was only decapitated, not fully demolished. The original blueprints and details are preserved in the New-York Historical Society. Computer-aided milling can add technological efficiency to replace the time-intensive labor that went into the original station’s creation. The project would benefit from the expertise of those who have recently carried out other reconstructions of a similar scale and complexity–on Dresden’s Frauenkirche and Paris’s Notre Dame, for example.

Richard Cameron calls his set of proposals the “McKim Variations.” This is because they are not absolutist, but provide templates based on the realities of what is possible. The first one, and arguably the most desirable, is the complete reconstruction of McKim’s original station, but with functional alterations to the flow of people and trains. The second variation is a compromise that leaves Two Pennsylvania Plaza in place where the old station’s Seventh Avenue façade used to be. This is an admission that proposing the demolition of recently renovated office towers might be a hard sell to whichever agencies and private developers would be involved.

And lastly, the third McKim variation leaves both Two Pennsylvania Plaza and Madison Square Garden in place because it’s well known that the Garden’s owners are resistant to moving. But this variation reclads Madison Square Garden in a classical façade harmonious with the rest of the station’s architecture, while keeping the structure wrapped in the Doric colonnade of the original.

These variations on the theme of McKim recreate some or all of his original spaces, but also add new programmatic features. For instance, the old sunken carriageways of the original are rethought as shaded arcades for porous accessibility to the surrounding neighborhood as well as local-scale retail. Stairs, escalators, and elevators to the trains below are tripled in coordination with RethinkNYC’s plan for converting Penn Station’s track-layout to the operating model known as through-running. And many more connections are forged underground to the existing subway stations and the Moynihan Train Hall.

Richard Cameron perhaps said it best when he launched his “McKim Variations:”

We believe that beautiful architecture, natural materials and plentiful light, space, and green affirm human dignity. We also believe a well-functioning, state-of-the-art transit paradigm tailored to the regional conurbation that New York has become—through-running—can and will ennoble the act of getting from point A to point B. This, too, affirms human dignity. If the tracks are New York’s circulatory system—the thing that enables it to go on living—the building is its heart and soul, the thing that incarnates what the city is living for. TB