Features

EverGreene’s Masterpiece: Jeff Greene on Art, Architecture, and the Alchemy of Preservation

An interview with Jeff Greene, executive chairman and founder of EverGreene Architectural Arts.

At age 24, a brash Jeff Greene founded EverGreene Architectural Arts, a small painting studio in New York City. Today EverGreene is the largest specialty contractor in the country, with the main office in Brooklyn and regional offices in Los Angeles, Washington DC, and Chicago. Artists, craftspeople, designers, conservators, and others work to preserve historic buildings, art, and artifacts.

Much of the work is news making: Evergreene has restored many of our country’s most iconic large-scale structures, including 39 state capitol buildings and more than 400 theaters. Greene is esteemed in the historic preservation field, holding an Arthur Ross Award from the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, among others.

flame on the Library of Congress.

Photos by Evergreene

Court.

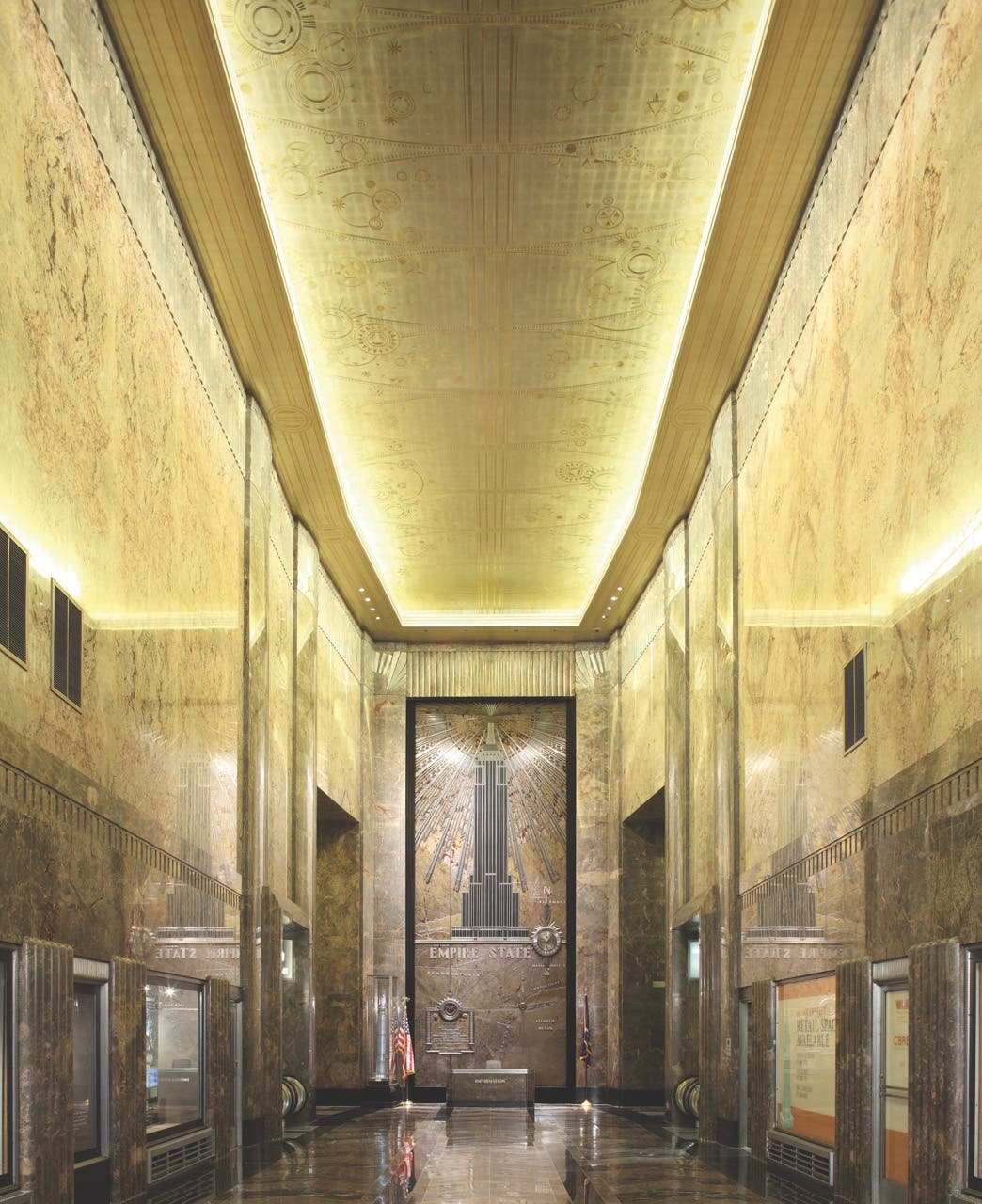

lobby ceiling, Empire State

Building.

When we spoke, Greene was preparing to head to Italy to work on frescos in a tiny chapel. He paused to speak with me for Traditional Building, always elegantly, in lush brushstrokes and fine detail.

Many subjects pop up: banal cities, working on the US capitol, the art of feeling, learning as you go. At one point he trades seats with me to ask a question, with his characteristic humor and intelligence.

Evergreene

Question: You grew up in Chicago. What was your life like in the ensuing years?

Greene: To make money through school, I painted houses and learned how to do frescos and plaster walls. I made my own paint; I ground my own colors. Then I got interested in the building arts. I was also interested in fine art. My brother Daniel Greene (a distinguished portrait painter) was a big influence. In 1980, I painted an art deco mural for a bank in Rockefeller Center. Working on churches and theaters, I learned decorative painting: stenciling, glazing, gilding, marbleizing.

I graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a degree in fine art painting, and moved to New York City. It is, and was, arguably the center of the creative art world. I got a rigging license and got into a lot of crazy construction jobs.

When did you see that art and architecture are a natural pairing?

In 1980, I started painting murals for Richard Haas (an American artist best known for architectural murals and his rendering of trompe l’oeil style). I realized I could combine architecture and art. Then, in 1986, I restored the office of then-Vice President George H.W. Bush to its original style of the 1880s. After that, I worked for five years on the Library of Congress, and went on to painting murals in the US Capitol.

What excites you about the field today?

There’s this wonderful chemistry, even alchemy, of bringing different fields together: conservation/science, craft, construction, architecture, and art. People are doing individual things, but the beautiful thing is that EverGreene brought them all together, respecting each discipline. This is the field of preservation. In the 1980s, this was relatively new. (See the Association of Preservation Technology: apti.org.)

I’m always digging into the dustbin of history, researching old techniques and materials to solve modern problems. It’s an endless learning process: finding out about unusual materials, like scagliola, zenitherm, and carton pierre. Every project has something new to teach us. With a forensic approach, we look at materials, pathologies, and mechanisms of deterioration, to diagnose the patient, which is the built environment or artifact. Then we apply our knowledge to solutions. The process of discovery is where the growth is, the excitement.

It seems that so many beautiful buildings are being demolished and replaced by boring structures. What can we as a society do?

(Greene pauses.) Mary, what’s the most banal town you can think of?

I name the town I grew up in, in North Texas.

Greene says, Oh, I know that town! It has an incredible courthouse, a gorgeous hotel, and a bank that will need preservation (built in 1920, remodeled in the ‘50s). Often people forget what makes a town unique. You can find meaning, satisfaction, even joy, in architecture in any town. This is what creates a sense of place.

What would you say to students who want to work in artistic restoration, while the world around them is fawning to the gods of technology?

Look, in 1900 New York City, there were more than 10,000 stonemasons; today there are less than 1,000. But the buildings are still there, and we continue to build. Architecture will always need restoration: stone, painted plaster, plastic. There is no shortage of buildings that need to be restored. Take the Lever House on Park Avenue in Manhattan, built in 1950. EverGreene helped restore the mosaics in this building. There is absolutely a necessity for these craft skills; this will ensure the future.

We need people who have intellectual skills and people who want to work with their hands. We need both the practical and pragmatic. We will need to embrace AI and other technological tools. We have to respond to the marketplace, but learn from the past. There will always be a need for restoration knowledge. We also have to preserve the skills as well as the objects.

Sometimes you talk about ‘heart’ in artful architecture. What does that mean to you?

It has to do with finding the art of feeling. We preserve things of value—high art or vernacular art—it doesn’t matter. At EverGreene, there is such camaraderie and cross-pollination. EverGreene is a little United Nations: Americans, Russians, Bulgarians, Eastern Asians, all coming from different traditions.

We’ve had Tibetan monks who were temple painters, Buddhists who worked on Catholic churches. Craftspeople are united: working with their hands, finding satisfaction, standing back and seeing the results. Hands, minds, hearts. I have all the faith in the world that the field will continue to evolve. TB