Features

Book Review: Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy

by Denis R. McNamara

Hillenbrand Books, Chicago, IL; 2009

256 pages; hardcover; more than 425 color and b&w photos; $50

ISBN 978-1-59525-027-8

Reviewed by Nicole V. Gagné

With this thoughtful and attractive publication from Hillenbrand Books, author Denis R. McNamara probes the deep meanings of not only liturgical art and architecture, but also the Sacred Liturgy itself, in an effort "to help pastors, architects, artists, members of building committees, seminarians, and anyone interested in liturgical art and architecture come to grips with the many competing themes at work today. The goal then is to drink deeply from the wells of the tradition, to look with fresh eyes at things thought to be outdated or meaningless, and to glean the principles that underlie the richness of the Catholic faith."

Readers in search of an impartial scholarly evaluation of this subject matter will invariably be disappointed by McNamara's book, as it is resolutely Catholic in its perspective and arguments. (Along with holding a BA in the History of Art from Yale University and a PhD in Architectural History from the University of Virginia, McNamara is also an assistant director and faculty member at the Liturgical Institute of the University of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary in Illinois.) So no one should be surprised when the author insists, "Any book about liturgical art and architecture therefore must be a book about Beauty, Truth, and Goodness," or that McNamara provides standards for those notoriously vague and subjective terms.

He defines Beauty as "the revelation of the ontological reality of a thing, the expression in material form of the innermost heart of the very identity of its being"; it's thus "the compelling power of Truth" and "reality as understood in the mind of God, who knows no untruth and inspires people to act toward the Good," with Goodness being known as "where human acts are made with moral sense, which is informed by grace-filled reason."

Modernism's departure from traditional forms is, not surprisingly, seen as an assault on Beauty, Truth, and Goodness: "Could that which was once Beautiful, True, and Good be no longer so, simply because the standard-bearing philosophers of Modernism have claimed a radical break between 'then' and 'now'?" In dissecting this question, McNamara takes his cues from the 2000 book The Spirit of the Liturgy by Cardinal John Ratzinger (the present Pope Benedict XVI), defining the epoch of humanity, which spans from the era of the Old Testament to the present, as "the time of 'image,'" [...] in which we have real genuine access to the things of heaven, but in the mode of sacrament" (his emphasis). Not until the end of Time as prophesied in the book of Revelation will the things of heaven be directly available, and then only to the select few who will meet the Deity's approval and be welcomed into eschatological existence.

Catholic church architecture therefore assumes a special urgency because its role is to make the ineffable material during this interim period of human existence. As McNamara explains, "a church is a sacramental building that makes present to us the realities of heaven and earth at the end of time [...] what heaven looks like, who is there, and what the nature of redeemed creation might look like."

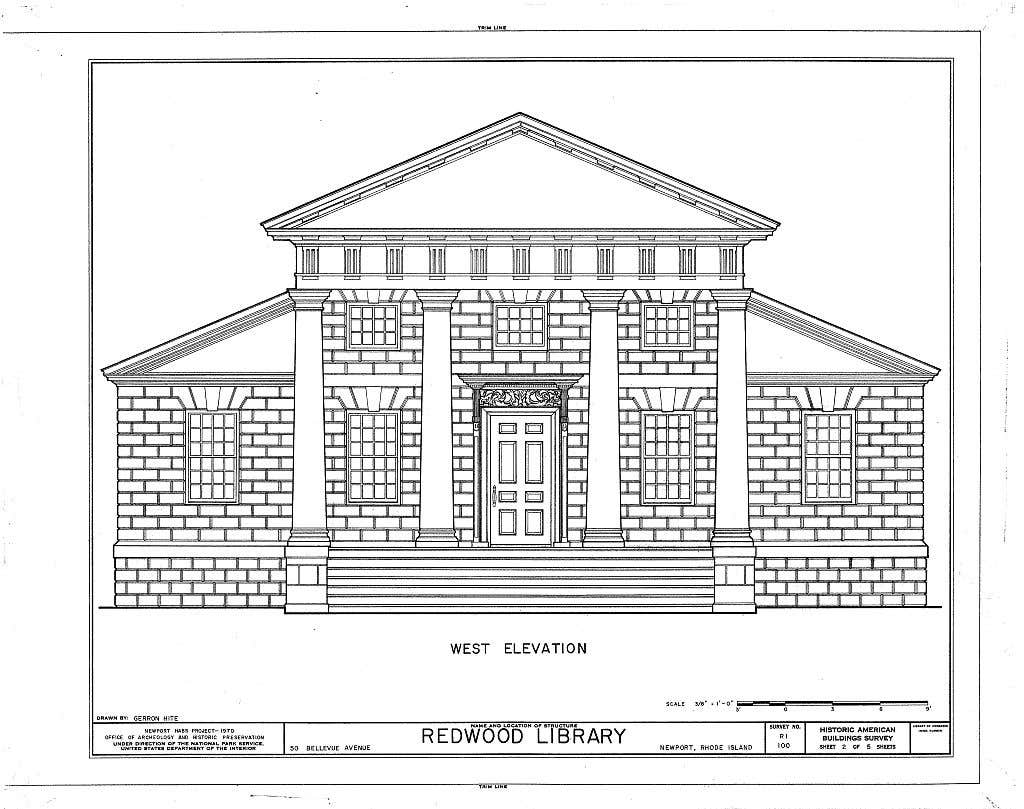

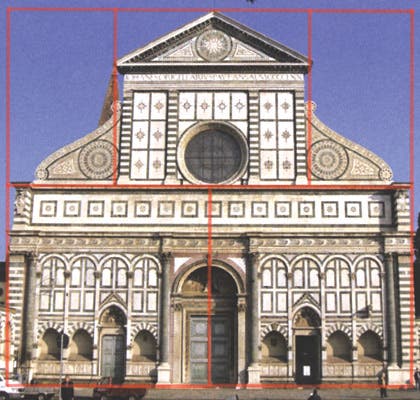

Catholic Church Architecture and the Spirit of the Liturgy is organized into five main sections. Part I, "Architectural Theology," argues that "church architecture [is] the built form of theology" and offers handsome examples of church design within the notions of beauty espoused by Saint Thomas Aquinas. Part II, "Scriptural Foundations," looks at ways in which churches have exteriorized and represented Catholic beliefs.

Part III, "The Classical Tradition," will warm even pagan hearts among traditionalists, insofar as it anoints Classicism as having "the goal of participating in that which is eternal and true," and interprets Classical precepts within that perspective. Part IV, "Iconic Imagery as Eschatological Flash," includes an examination of an aesthetic middle path, with McNamara arguing that "liturgical art should be naturalistic enough to be legible, abstracted enough to be universal, and divinely idealized enough to be eschatological." Part V is entitled "Introduction to the Twentieth Century."

To its credit, McNamara's vision is most compelling in the Conclusion. There he reminds his readers, "An artist or architect who submits his or her will to the Holy Spirit will not be left unaided." Illustrated with impressive glimpses of 21st-century Catholic art and architecture, this final discussion demonstrates how, when faith and inspiration go hand in hand, the results can surprise and delight the mind as well as enrich the spirit.