Roofing

Traditional Roofing for Historic Buildings

Traditional roofing materials continue to lead the pack when it comes to historic public buildings.

Traditional roofing materials — think sheet metal, clay tile and slate — continue to crown public buildings large and small not only because of their timeless beauty but also by virtue of their proven durability. However, even though these traditional materials are typically best installed with traditional methods, more than ever, changes in the roofing industry, environment and especially in historic buildings themselves have to be taken into account.

What's Used Where?

Over their long history, the big three materials have developed such a universal appeal and tremendous versatility that, typically, their choice is governed less by the high-minded dictates of architectural style than the practical considerations of a building's use, place and image.

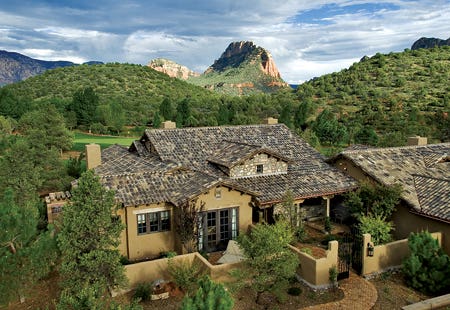

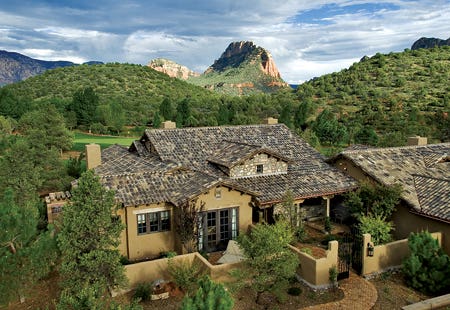

According to Michael Lukis of Tile Roofs, Inc. in Frankfort, IL, clay tile generally appears on more permanent structures such as churches, libraries and village halls. "You'll find Spanish or Mission tiles, for instance, on a Greek church and even a lot of Catholic churches," he says, "but not necessarily coordinated historically with the architecture." Lukis adds that, in his experience, churches and public buildings that went up in Chicago and the Northeast in the 1920s and '30s were often roofed in tile. "Certainly Spanish tile but even some French and interlocking tile — all the types equally popular at the time for houses."

A. Tab Colbert at Ludowici Roof Tile, Inc. in New Lexington, OH, adds that clay tile in large measure historically followed a building's type and where it was located. "An awful lot of banking institutions and government buildings predominantly use what's called a pan-and-cover system," he says, "where there's a pan — usually a radius product such as a straight barrel Mission tile— and then a cover that gives the opposite radius going over the top of that."

He adds that a straight barrel Mission product is very widely seen on government buildings in Washington, DC. "But when you get to court houses, libraries and banks, they often end up with a pan that may be radius or it may be flat, but it's topped with a Greek cover that is angled, and makes a very strong, sturdy statement that looks like it's been there for centuries." Not surprisingly, he says Spanish and Mission tiles tend to dominate in Texas, "but go to Florida, and you'll find a lot of interlocking flat tiles as well." Chicago, he says, "likes French." "There are little enclaves all over; it really depends."

Robert Raleigh III of Renaissance Roofing in Rockford, IL, adds that some of the same observations apply to slate. "Typically we find slate on church structures and court houses — both standard and graduated slates — but it kind of runs the gamut." He notes that most college campuses have an architectural style, so similar roof materials tend to appear in groups, with one campus having mostly slate while another may be mostly clay tile. "Of course, the more distance you travel from the slate-producing regions in the East, the more transportation costs had an impact on what materials were used, so the farther West you go, I think the use of slate declines. Nonetheless, areas like St. Louis have a large population of slate roofing systems."

When it comes to slate types, he adds that, in his experience, there is some regionality. The distinctive, lustrous blue-black of Buckingham, VA, slate is "pretty identifiable in color and texture" for example. "We do see it here in the Midwest, but not extensively — in fact, historically it probably wasn't distributed widely anywhere in the U.S. other than around the immediate area of the quarries." In contrast, he says Pennsylvania soft vein and Vermont slates are very common in the Midwest. "We actually also see a few roofs of Monson slate that came out of Maine here in the Midwest."

Switching to sheet metal, Nick Lardas of NIKO Contracting in Pittsburgh, PA, has similar remarks. He says they are particularly known as specialists in sheet metal, as well as other materials, and for historical roofs they typically see work in copper and terne metal — "traditionally, metals you can solder," he says — but in the South and Southwest they find more galvanized steel, though that picture has been changing of late. For ornamental work, such as dormers and cornices, the metals are either copper or a mix of sheet zinc, and galvanized steel. "Galvanized is limited though," says Lardas, "because the metal is not readily formed into more complicated shapes, so you see it more in brake-formed work in making cornices."

He notes that sheet zinc — a material with a long history in Europe, but little seen in America and not previously considered a traditional roof — has been coming on strong in the last 15 years. "Zinc has its idiosyncrasies, such as it can't be installed in a soldered flat seam, so the roof has to be standing seam or batten seam," he explains, "but it has a nice, natural look for a metal as well as long life."

The majority of NIKO's work is on existing buildings, ranging from New York, to Michigan, to Florida. "In a historic building, if the roof was metal the owners typically want to stay metal."

Details, Details

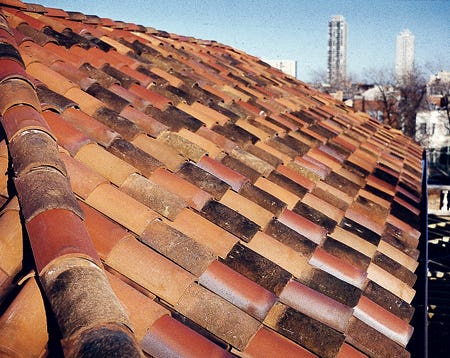

Time-tested and long-standing as these materials are, they nonetheless can face modern issues in installation, restoration or sourcing. The longevity of clay tile, for example, frequently means a roof may have outlived its original manufacturer, but that also translates to re-usability. "Typically the term we use is lift-and-relay," says Colbert, "where the tile is inspected and analyzed and, when in good condition, the roofer just takes the tile off the roof, puts down new felts, and then puts the same tiles back on the roof."

Colbert explains though that in situations where special pieces were made in the past, those pieces cannot be re-used. "Field tile is usually nailed or screwed down, but the accessories — tiles covering the hips, ridges and so on — are put down in a mortar base. So when you remove these accessories, the mortar may come free of the field tiles but, in many cases, the accessory will come free of the mortar and break, so you will have to re-make those accessories."

Colbert notes that while sometimes difficult, anything once made by his company can be made by them again. "We're constantly making a lot of different products, and doing it in addition- and renovation-size quantities as well as large quantities." What's more, the same applies to long-gone products. "We do exact matches of other tile producers, such as Mifflin Hood," he says. "They made a very good tile used on a lot of public projects throughout the South but, unfortunately they went out of business in the 1950s."

Colbert says the process starts with carefully measuring an actual example of the product. "We need to see the product because that will determine 1) what plant it came out of (and thereby what clay was used); and 2) what we need to do to be able to engineer the tile to today's clay shrinkage rates."

Lukis points out that tile's longevity adds another dimension to sourcing. "Oftentimes we have a client restoring a 60- or 80-year-old roof who needs replacement tiles and fittings, so for those kinds of projects there's a lot of demand for our recycled and reclaimed materials that provide an exact match in make, design, appearance, age — everything!"

On the other hand, sourcing slate to match historic roofs is not a big problem, according to Raleigh. "Slate requires lead time — sometimes as much as six to 10 weeks to get an order — so it's a matter of planning more than anything. You can't go pick up slate at your local supply yard as you can with other roofing materials. Identifying the colors of original roofs is typically not a problem for us."

As he explains, "Slate is a natural product, so it varies from one day to the next as it comes out of the quarry, so what was quarried 100 years ago is not going to be identical to what is quarried today because it's from a different part of the ground." Raleigh adds that since Pennsylvania slates have an accepted life expectancy of around 80 years, "most of the Pennsylvania slates that we see here in the Midwest are at the end of their service life and have begun to deteriorate and fail. Vermont slates are typically in good condition, but should be considered for complete replacement, and Buckingham slates, which tend to last, are still in excellent condition."

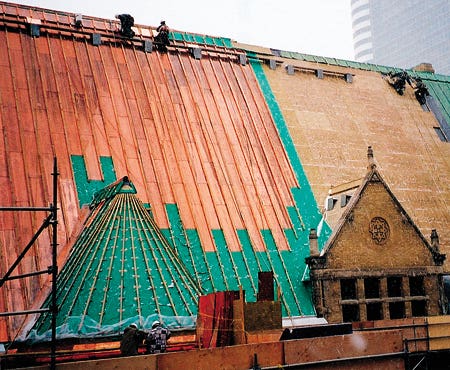

Surprisingly, the supply of sheet metal is not immune to the caprices of the manufacturing-business world either. Lardas notes that the longtime sole producer of terne-metal roofing — Follansbee Steel of Follansbee, WV — closed its doors in 2012. Terne is a tin alloy that, when plated to sheet steel, has been the source for the iconic and highly durable standing-seam roofs across the U.S. since the early 19th century.

"While traditional terne (or TCS) is no longer available," says Lardas, "you can still get terne-coated stainless steel and terne-coated copper, now made by Revere Copper, which acquired much of the Follansbee production equipment." He notes that while effective stand-ins, these materials are not the same. "If you have, say, a built-in gutter, your choice is now either copper, lead-coated copper, terne-coated copper (called Freedom by Revere) or terne-coated stainless steel, which is a little trickier to work with. It's not only harder to solder for flat seams, because it is prone to hot spots, it is also less forgiving than copper."

He adds that, in some projects, painted-metal roofing systems are also considered as an alternative to terne, though suitability depends upon the complexity of the roof and the goals of the client. "The detailing of roof intersections is not the same," he says, "relying more on sealants than traditional seaming techniques. It all depends upon the project and the client."

More than Just Materials

When traditional roofing projects hit rough water, however, it's likely not the materials themselves that are the cause but something off-course in the planning. "Most architects have a good grasp of metal roofing," says Lardas, "But occasionally we see a disconnect between the specs and the detailing — for example, specifying a standing-seam copper roof but then incorporating details for a painted metal roof system." He adds that to help with these questions leading industry organizations such as the CDA (Copper Development Association), SMACNA (Sheet Metal and Air Conditioning Contractors' National Association) and Revere Copper have long published excellent standard detail and practice references.

Raleigh adds another perspective. "There are a lot of idiosyncrasies that can get overlooked at the spec-writing level, but the experienced contractor has a hard time ignoring them," and in Raleigh's view, this can be a source of problems long before installation. "When projects specified in this way are then let for bid, you get a large range of results in those bids — due in large part, I think, to inaccurate specifications or documentation of existing conditions." He adds, "It's hard to justify such large bid spreads when everybody's considered an equal or qualified to be bidding the work."

While roofing projects can suffer when the specs are inconsistent with the desired material, just as problematic is when they don't match the historic building. "You run into that all the time," says Lukis, "Someone has not done a good enough survey of the existing conditions." He cites a project where change orders have run nearly $100,000 — more than 10 percent of the contract — because of unforeseen existing conditions that were not researched before the project was begun. "Some architects really do their homework and have encountered these things before, so they know a little more what might come up on a roof restoration. But then there's the guy who's never really been involved in those kinds of projects, didn't do his homework and is going in blind."

Taking another step back, Raleigh observes that, "A lot of times when people think of their roof, they don't give enough attention to the flashing and gutter system, which typically receives 100 percent of the wear and tear on the roof. These are not stand-alones but integral with the roofing system." He notes that many a built-in gutter system is well over 100 years old, but patched and relined many times so, by today, they have a lot of hidden issues — structural framing, decking — that, if not investigated ahead of time, start to cascade and create a lot of tension when they are opened up. When there's the opportunity, Raleigh says he's a firm believer in some destructive testing. "'Let's discover all these problems ahead of time,' we encourage our clients, 'and discuss them before we have a contract and everybody's arguing about who's responsible for what.'"

Taking another step back, Raleigh observes that, "A lot of times when people think of their roof, they don't give enough attention to the flashing and gutter system, which typically receives 100 percent of the wear and tear on the roof. These are not stand-alones but integral with the roofing system." He notes that many a built-in gutter system is well over 100 years old, but patched and relined many times so, by today, they have a lot of hidden issues — structural framing, decking — that, if not investigated ahead of time, start to cascade and create a lot of tension when they are opened up. When there's the opportunity, Raleigh says he's a firm believer in some destructive testing. "'Let's discover all these problems ahead of time,' we encourage our clients, 'and discuss them before we have a contract and everybody's arguing about who's responsible for what.'"

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.