Windows & Doors

Restoring Trinity Church Wall Street: A Gothic Revival Masterpiece

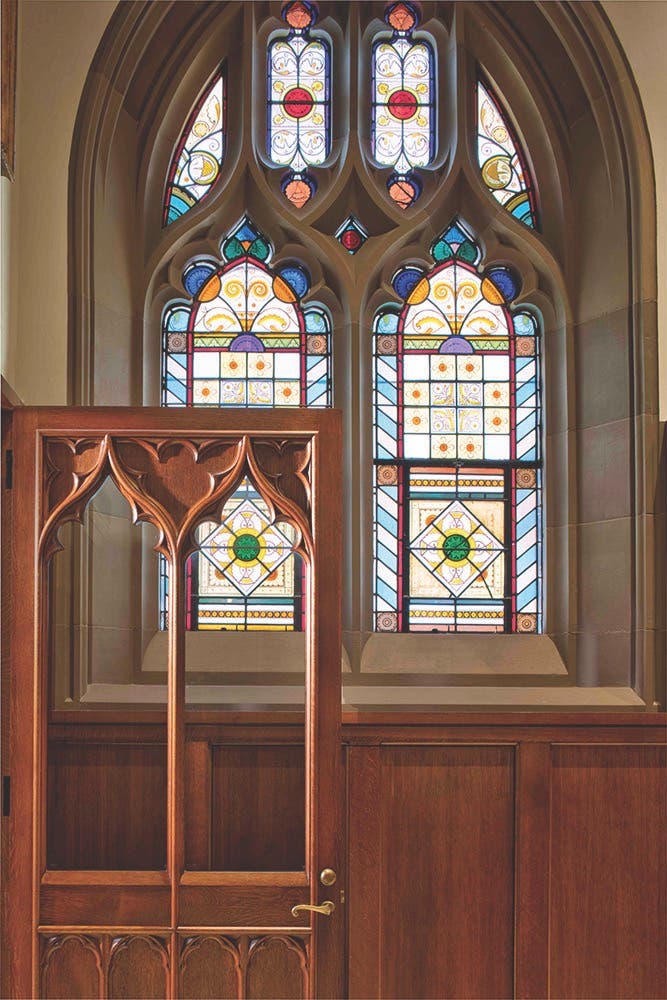

Long revered as one of New York’s most outstanding and inspiring houses of worship, Trinity Church Wall Street is the soaring, brownstone centerpiece of lower Manhattan that introduced the city to chocolate-colored masonry and the revitalized Gothic style. Completed in 1846 by British-American architect Richard Upjohn to replace an earlier church, it broke new ground in ecclesiastical architecture with its direct expression of structure that is supported, rather than concealed, by ornament.

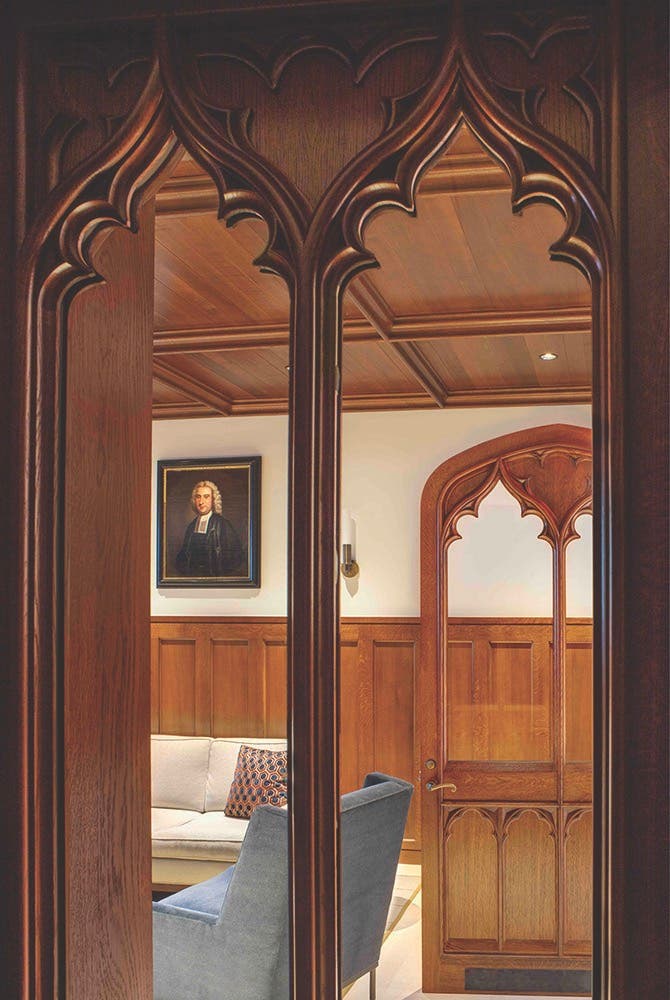

Refurbished multiple times during its history, by 2019 deferred maintenance, obsolete mechanical systems, and the need for new clergy and visitor spaces caught up with the interiors, leading to an extensive, six-year restoration and renovation campaign. This included restoring and rebuilding numerous doors, oak-paneled rooms and ceilings, cabinetry, and trim by Zepsa Industries of Charlotte, North Carolina.

Building interior and exterior doors was a major phase of the project, says Steve Ballinger, president at the company. “The call was to make the doors in the same Gothic style, and with the same details and quarter-sawn white oak, as the original work.” This traditional cut not only produces durable boards with a pronounced straight grain, in oak it reveals the tree’s medullary rays for a beautiful “fleck” appearance. “It’s always a careful process to source material to match existing installations, but we’ve gotten good at it over our 40-plus-year career,” he says. “The oak in old buildings has a certain character that is hard to find.”

Most of the doors are traditional, frame-and-panel design, but with a modern twist. “In the old days doors were made out of big, thick, solid pieces of wood,” says Ballinger, “and if they’re still around 200 years later, that’s a blessing.” As he explains, most wood that thick will warp and check over time, “So what we use now is stave core construction with a surface layer of the specified oak over the stave core.” Stave lumber core doors are engineered from blocks or strips of wood of the same species glued together to establish a solid structural substrate. “This keeps the frame members straight so they’ll remain stable and perform over time.”

Key to durability is Zepsa’s choice of mortise-and-tenon joinery. “The modern trend is to use dowels or mechanical hardware to hold the parts of the door together. We know mortise-and-tenon is the best, most stable method, as well as being historically correct.” He says they glue full-size mortises and tenons the way it would have been done traditionally, including in 1840. An added challenge was to engineer the doors, walls, and floor for state-of-the-art automation and security. “We had to make doors that look 200 years old, but when you push a button on the wall, they open, close, and lock by themselves.”

The engineering behind new, large cabinets and flat drawers to hold formal garments for church personnel became another joinery puzzle. “They’re 10 feet wide and extend out 42 inches beyond the cabinet, so the challenge was to construct the drawers so they don’t rack as they’re opened and closed.” He notes that with ordinary drawer slides, even a drawer three or four feet wide is likely to get stuck in operation. “So there’s structural steel, creative applications of hardware, and some crafty engineering to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

More woodworking ingenuity comes into play for renovating the music and choir practice room to some stringent acoustic requirements. In collaboration with MBB architects, the room is lined with multiple angled doors with inter-panels containing sound-absorptive material that can open or close independent of the larger door. “These are lockers for the choir members and director,” he says. “They have tall, narrow doors, and the members can manipulate the inner panels to enhance the sound-deadening within the room.” In front of the window wall Zepsa also built an enormous, sliding pocket door that can be closed for privacy and for additional acoustical control.

Though the Gothic Revival of the 1840s may at first seem to be a return to the Middle Ages, it was in fact made possible by the Industrial Revolution. In England, A.W.N. Pugin the seminal architect and exponent of the style whose designs informed Richard Upjohn, enthusiastically promoted the use of new machinery and technologies for stone construction and wood carving. The same held true in America. “We do a lot of laser scanning on projects, and yes, our CNC equipment is a useful part of the shop operation,” says Ballenger, “but on this project, the final carving was done by hand.” As he explains, they often remove part of the material with CNC carving tools—the heavy lifting, so to speak—then finish it by hand. “It’s an old-school/new school philosophy: lots of hand work supported by state-of-the-art engineering. Machinery is great,” he adds,” but we owe the final outcome to the skilled craftspeople actually putting all these parts together and doing the finer aspects of the work by hand. It’s a combination of the old and the new.” TB

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.