Product Reports

Moldings, Nature, and Beauty

I think that it’s safe to say that most of us have experienced times when we were profoundly moved by the beauty of the natural world. We may have surveyed the expanse of the high desert, wondering how such a complex landscape could make us feel so centered and calm. Or perhaps we looked across an alpine meadow and gazed at the complex, chiseled profiles of distant mountain peaks. Or maybe we’ve walked along the seashore at sunset and were struck by the way the receding waters rippled over the multi-colored stones in the sand.

Experiences such as these are universal among us. Over the ages, and across diverse cultures, one thing that certainly unites us is our ability to find and experience beauty in nature. It seems as though this is a part of our being. Is the ability for us to directly experience the beauty of the natural world around us a part of our DNA? Are we hardwired to receive this gift? It certainly seems so. We may take our children to a great forest of old trees, watching as they gaze in wonder at the complexity of the branching canopy of shimmering leaves. We don’t have to teach them that it is beautiful; they know this innately. Experiences such as this are their birthright.

One of the aspects of classical architecture that makes it so efficient at creating beauty in the built environment is the fact that embedded within the grammar are diverse alignments with nature, explicit and implied. And these alignments start with the classical moldings, since they are the “atomic units,” the basic building blocks of the classical elements.

Engaging the Organic

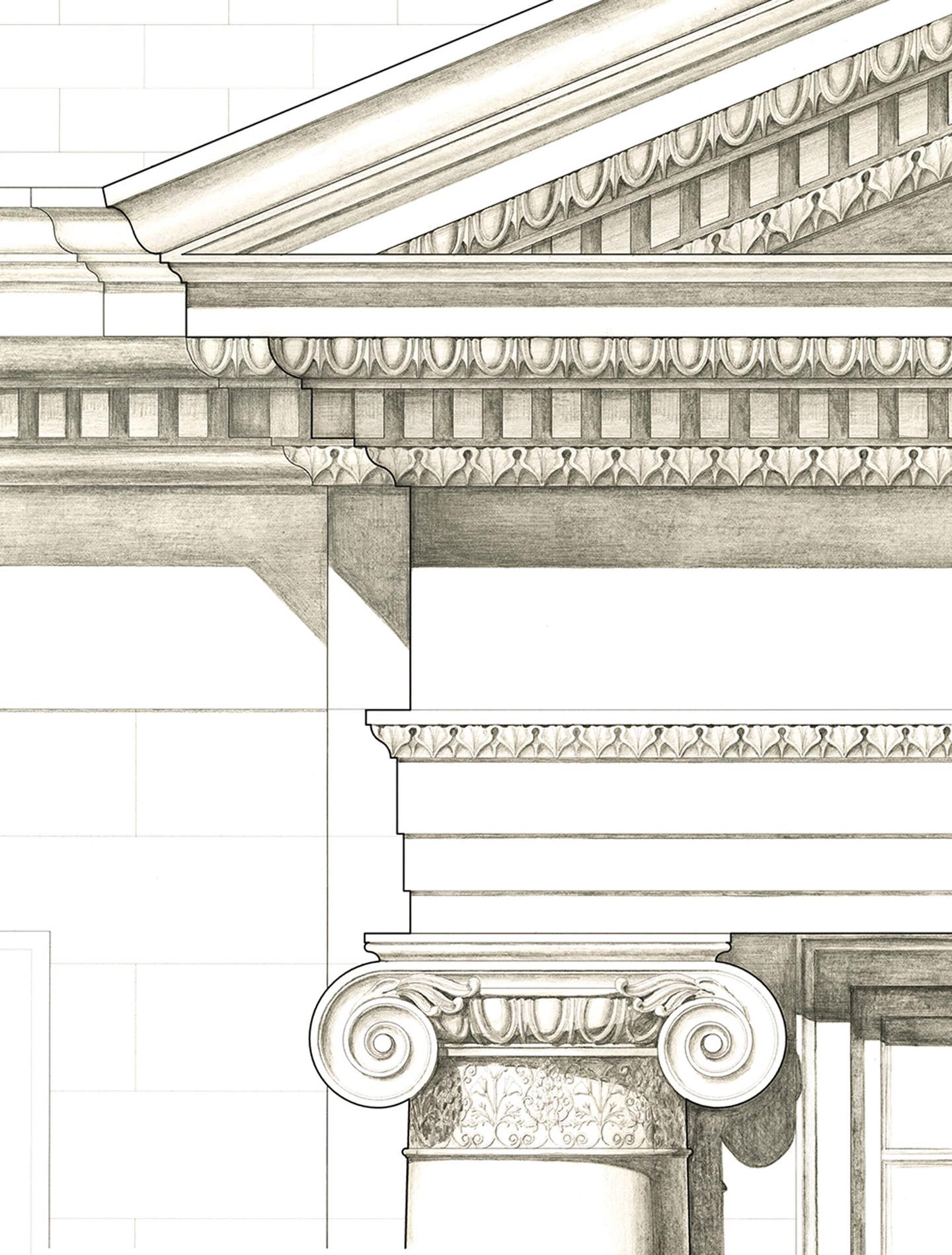

Moldings are often explicitly decorated in ways that directly emulate natural forms. The most famous example is the egg and dart motif. This pattern is the traditional style of embellishment of the ovolo (quarter-round) molding. (See Photo 1.) First appearing in primitive Greek architecture around the seventh century BC, it is identified by a dominant row of hanging egg forms, alternating with intervening stem or spear shapes, the “darts.” There are various myths about the origins of the egg and dart. It might have been intended to symbolize the dualities of life and death, or of male and female.

We can see great variety in egg and dart moldings over history and different cultures, and designers should feel free to creatively vary their design. Sometimes the eggs are clustered closely together, and the intervening darts are minimized. Other times, the eggs are spaced further apart, and the darts more dramatically pronounced. But whatever the exact details, the sculptural shapes of the egg and dart pattern are potent emblems which remind us of natural forms.

Similarly, the traditional embellishment of the cyma reversa molding is the tongue and dart. (See Photo 2.) This theme consists of a drooping, tongue-like shape, alternating with intervening pointed darts. Originating in Greek designs from the fifth century BC, the tongue and dart decoration evolved with many variations, including the leaf and dart, which typically features various vegetal motifs. The “leaf” and “tongue” themes may be understood as appropriate for the cyma reversa molding because their draping form can comfortably conform to its complex profile.

Engaging Detail at All Scales

As we have seen, decoration which explicitly emulates organic form is one way that the elements of classical architecture are aligned with nature. But it is certainly not the only way. Implicit within the structure of the classical language is another link to the geometry of nature, and the moldings contain an important key to unlocking that connection.

When we look at the natural world, one of the aspects of it that leads us to the experience of beauty is the engaging complexity of natural forms. The world around us abounds with intriguing form, geometry, and texture, and these elements entice our senses at a variety of scales.

Imagine that we are observing a mature tree on the crest of a hill, from a distance. The overall shape of the tree is a lively and engaging one—generally symmetrical about the central vertical axis of the trunk, but with a pleasing randomness to the profile. As we move closer to the great tree, we start to see the branching of the trunk and limbs of the tree—asymmetrical but following a general rhythm and theme specific to its species. As we approach closer yet, we begin to pick up more detail: the craggy, deeply textured surface of the bark on the trunk, and the delicate, repeating shape of the individual leaves. And if we were to pick one of the leaves and examine it closely, we’d see at the finest scale a complex structure of veins embedded within it, reiterating the branching theme we saw at the larger scale.

A Simulacrum of Nature

This kind of relationship between the very large and the very small is the prevailing condition throughout the natural world. Put simply, this is the way nature works. The language of classical architecture, as a simulacrum of nature, operates in the same way.

When we observe a beautiful building from a distance, we are able to consider the form as a complete composition. Great works of architecture are able to engage our interest at the largest scales. We might be captivated by a bold, symmetrical profile highlighted against the sky. (See Photo 3.) As we approach the building, the complex details of the smaller scale elements of the architecture begin to speak to us. (See Photo 4.) As we move to very close range, the moldings that make up the elements start to engage us with a lively play of shade and shadow on their surfaces. And if we look even closer, decorative embellishment of the moldings provide an even finer gradient of detail to delight us. (See Figure 5.) The visual and tactile qualities of the small-scale elements of classical architecture are key reasons why we find these buildings so beautiful. It is at this range where many modernist buildings, with smooth, minimalist surfaces and unadorned intersections, fail to engage us in the same way.

This ability for the language of architecture to connect to us at a variety of scales is one of the most potent ways that classical architecture reiterates the natural world. Great architecture connects with us in a series of overlapping realms, each level engaging us in its own way. And the moldings, by enriching the architecture at the scale of the very small, the human scale, are indispensable ingredients in this integrated tableau.

See more on moldings