Product Reports

Lighting for Historic Buildings

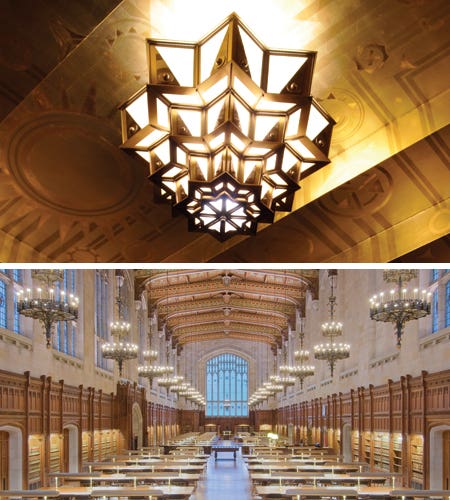

Few things add to the vintage ambiance of a public building like interior lighting in step with its era, but lighting a historic space is rarely as simple as dusting off some antique fixtures. In many cases, lights from the past have either been ham-handedly made-over in the periodic switches from oil and gas to electricity, and incandescent to fluorescent, or simply deemed too obsolete to keep. What's more, modern demands often mean that even when original fixtures exist, they fall short of today's light output and energy conservation needs – or there just may not be enough of them to fill an expanded space. Fortunately, dealing with these issues is the stock-in-trade of some venerable companies that stand ready to help with decades of skill and expertise.

Trading Light-ly

Outsiders might assume that the historic lighting business follows trends in fixture age or design but, it turns out, there is no typical project. "We see a little bit of everything," says Edwin Rambusch of Rambusch Lighting in Jersey City, NJ. The company has taken on projects from crystal chandeliers of the candle era, to gas-electric fixtures, to early electric, to contemporary fixtures.

Woody Crenshaw of Crenshaw Lighting in Floyd, VA, says that "Over our long history of doing custom lighting restoration, we've seen projects from many periods, but most of our commercial work has been on fixtures from the first three decades of the 20th century." However, he adds, "We are often called to electrify old gas light fixtures from the 19th century, some of which have already been through a previous restoration."

At Ball and Ball in Exton, PA, the forte is the 18th century but, as Bill Ball notes, "18th-century fixture styles are used in interiors of a lot of other eras," and they are equipped to tackle a wide range of styles because, "we have a large design library that we consult."

According to Gary Behm of St. Louis Antique Lighting in S. Louis, MO, his company also relies on its extensive collection of antique lighting catalogs, and with a project list that includes state capitols, universities and ecclesiastical buildings, it works on fixtures from the gas era forward, roughly 1840 to 1940.

That being said, decades of serving a particular clientele base tends to give a business its own character. Crenshaw, for example, specializes in three aspects of custom lighting: historic, church/sacramental, and fixtures for new construction. As Crenshaw explains, "We've done a lot of historic lighting projects in Washington, DC, that follow a three-phase scenario: 1) take down the historic fixture and transport it to our facility; 2) repair, restore and finish the fixture while the interior of the building is demolished and rehabilitated; 3) artfully retrofit contemporary lamp sources in the historic fixture, then re-install the fixture in the finished building."

This restore-during-rehab routine holds true for most of the public buildings Crenshaw Lighting works on, such as historic theaters, old courthouses and federal government buildings. "Generally, the building is taken off-line for a couple of years," says Crenshaw, "but there are cases, as in a historic hotel, where we may be working in the ballroom while the rest of the building continues to operate around us."

Ball and Ball also takes on repairs and restorations, from the common wear and tear of age to catastrophic damage. "We recently had a project repairing a lead-crystal chandelier that fell two stories in a stair hall," says Ball, "because during cleanings people had continued to spin it until it came unscrewed from the ceiling." Another project was a fire-damaged building in Philadelphia, where the company removed, cleaned and mothballed the chandelier until the building was finished. Ball says it does a lot of high-end, non-residential, custom manufacturing as well.

Behm notes that his business is organized around project areas he calls restoration, replication and innovation, and that it has a modern fabrication shop capable of manufacturing nearly anything in metal. At Rambusch, the lighting division is in charge of designing and producing custom and engineered lighting and, as a company in the industry for over a century, they have even been called in to restore and refurbish their own work.

The visual richness of the materials in many historic light fixtures is part of what impresses the visitor to a theater or cathedral but – no surprise – there is more to this effect than meets the eye. "To be a good restorer, you have to have the skills to create the fixture from scratch, to work with castings and extrusions and other ways of crafting metal and glass," says Crenshaw, "and be very sensitive to them, particularly with hand-rubbed finishes." He notes that just obtaining certain types of metals, such as nickel-steel, silicon-based wrought-iron and various metal finishes, can be a challenge. "Sometimes we have to go overseas to Europe or China for high-lead crystal or hand-blown glass," he says. "A lot of the American glass industry went away in the 1970s, due to the difficulty that small, specialty producers had with workplace regulations."

Improving on Edison

What all companies stress is the critical role of energy upgrades in their businesses – and their expertise. As Crenshaw puts it, "An important part of the art historic lighting restoration is the ability to integrate ballasts and new lamp types into existing fixture lamps – in other words, to retain the look of 100-year-old incandescent lamps, but have high-efficiency lighting."

Behm takes an even broader view. "Restorations are generational," he explains, "sometimes every 30 years, but perhaps every 50 years, due to periodic changes in both style and technology." He notes that, "From the 1940s through the 1960s people took out many of the beautiful incandescents," in the seismic switch to fluorescents (and to salvage brass for the war effort). This shift eventually led to a revival in historic lighting when period styles were re-appreciated in the early 1970s. Behm suggests that the increasingly rapid progress in lighting technology is reminiscent of Moore's law for integrated circuits, where performance doubles every two years. "More likely is that the technology will keep improving and become steadily better – smaller and more energy efficient – at a faster pace."

Until that time, historic lighting companies have to be on the leading edge of the technological curve while keeping a foot in the past – and be nimble business people to boot. According to Rambusch, "We find that certain clients are interested in retrofitting and upgrading historic fixtures for new energy standards, while others just want to go all new." As an example, he cites a state capitol that, having long-term goals, will likely see original fixtures as important to retain, while a developer who plans to sell his building in a few years, may not feel the same way or want to make such an investment. "The important part is to have someone early in the process make the decision."

These decisions can be tricky because new lighting, like so much else in technology, is a moving target and a balancing act. "Compact fluorescent has good color temperature (2700K – 3000K) at about one-quarter the energy needs of incandescent with the same lumen output," says Behm. However, he notes that the new generation is LED (light-emitting diode), which is quickly gaining popularity because it is low on power consumption and has a very long lamp life. "Because LEDs are so small," he says, "they can be grouped into any shape – even put in long runs to make ribbons of light."

LEDs come in several colors, and their versatility, combined with programmable control systems, has revolutionized lighting design over the last decade. Nonetheless, he notes, there are a couple of problems with LED lamps in general. "First, they are heat sensitive; second, they don't have the lumen output of other, more traditional sources. Also, the lamp cost is still fairly pricey, so when you compare lumens-per-watt in a project cost-benefit analysis, LEDs will not get the job done in some applications and more traditional sources are still preferred. So there is still a lot of room for growth in this technology."

Ball agrees, noting that, "It's still the early days of LED." Over and above the upfront cost, he says, there's "still a lot of concealment necessary, particularly for ballasts." Ball says he's waiting for someone to come up with an LED lamp that looks somewhat flame-like in an 18th-century chandelier – even similar to an incandescent candelabra lamp. "Lots of people may be trying, but we have yet to see anything suitable." He adds, "We can do any lamping, and there's definitely a trend towards compact fluorescent, but incandescent is probably what we still see most."

Another aspect is balancing aesthetics with economics. "In some historic projects, people use self-ballasted compact fluorescent lamps with standard base sockets, which have a light capability in the 15-watt to 40-watt range; some are even dimmable," says Behm. However, such lamps generally have a shorter lifespan. "You generally get longer lifespan with integral ballasts, which are more complicated to install, of course, but consequently the maintenance costs are less because lamp replacement costs are lower." Again, part of the art of good period lighting design is the challenge of hiding ballasts and indirect sources in clever places while making period lamps and fixtures look exactly like the original.

Should you think that lamp and ballast types and styles are economic options left to the client, or at least mechanical choices for the people actually working on the fixtures, on larger project, that is not the case. "Professional lighting designers or electrical engineers are the ones who usually make such decisions," says Behm, "and when it comes to historic lighting, there are maybe a dozen people in the country who are up to the job." He says they must have up-to-date knowledge of not only lighting engineering, but also architecture, history, fixture design and even finishes. He adds that it is not the generally the realm of architects either, but there are several firms with historic lighting design professionals on their staff.

New Lumens

Another significant part of historic lighting art is creating totally new fixtures in historic styles. Given an existing example, a typical project Crenshaw describes is for the U.S. Justice Department where the company took down and restored 800 historic fixtures, then replicated 300 more in the Art Deco style to hang in newly created spaces. "The challenge is greatest when you have two identical fixtures, old and new, side-by-side."

Rambusch Lighting had a related but different kind of task in the Empire State Building Lobby when they were called in to resurrect a lighting fixture that was planned for the 1931 space, but never executed due to the economic limitations of the Depression. However, where the only references are historic documents, the project may resemble the Kansas Statehouse where St. Louis Antique Lighting worked with a team of historians and designers to replicate 1880s Mitchell, Vance gasoliers based upon historic photos and catalogs.

But suppose the call is for new, historically appropriate lighting where there is nothing to copy – and a copy is not desired? One approach is the strategy Rambusch Lighting has developed over many years. "We call it design-driven innovation," says Rambusch, "or design consistent with the space." In these cases, the fixture will not be a replica but follow the design of the building, yet be something new.

As Rambusch explains, one of the challenges in such a new design is to get all stakeholders understanding and expecting the same thing. The process starts with questions. "What is the goal for the space? If it's decorative ambiance – shiny lights, for example -- that's one thing. If it's actual work light, then there will be much more stringent requirements, such as worrying about hot spots."

"A very important in-between step is the concept sketch," he adds. "Then, the concept sketch becomes the basis for other parameters, including price." Many of these concerns come to bear in large projects, such as the restoration of the Utah State Capitol. "Another important issue is whether you design to the building or design to the engineering," says Rambusch, "and this is one of the many challenges that makes lighting fun."

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.