Product Reports

hinge history

Hinges are part of every door, permitting the door leaf to open and close. They are used on entrances, cupboards, casement windows, pianos, and smaller objects, such as jewelry boxes. There are many types of hinges for these different purposes, each providing the required pivoting function.

History

The earliest known hinge is the vestige of a socket in stone that received the pivot for a heavy wood fortification door in Hattusa, Turkey, c. 1600 BC. (Figure 1) In 957 BC, chapter 1 of Kings 7, verse 50, describes Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem as having gold doors with gold “sockets” for the innermost room. A bronze hinge found in Egyptian ruins dates to c. 760-650 BC and was inscribed with a subsequent king’s name to mark the succession.

Similar pivot hinged doors were found in Mesopotamia from c. 5th-4th century BC. The Romans were serious about their hinges, designating the Roman goddess of the hinge, Cardea (Figure 2, above), to preside over both door and cabinet hinges. By the late 17th and 18th centuries, H- and L-strap hinges had become common.

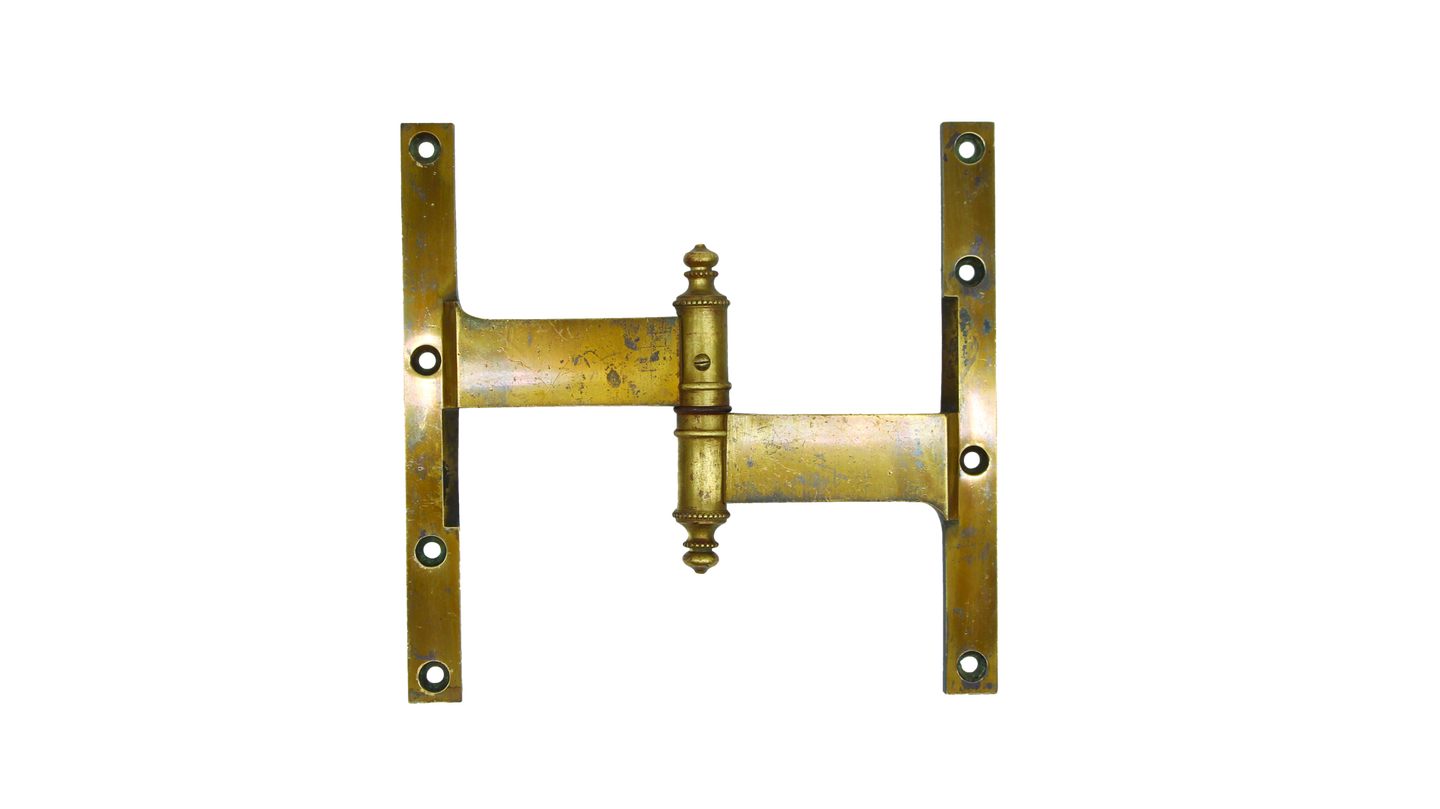

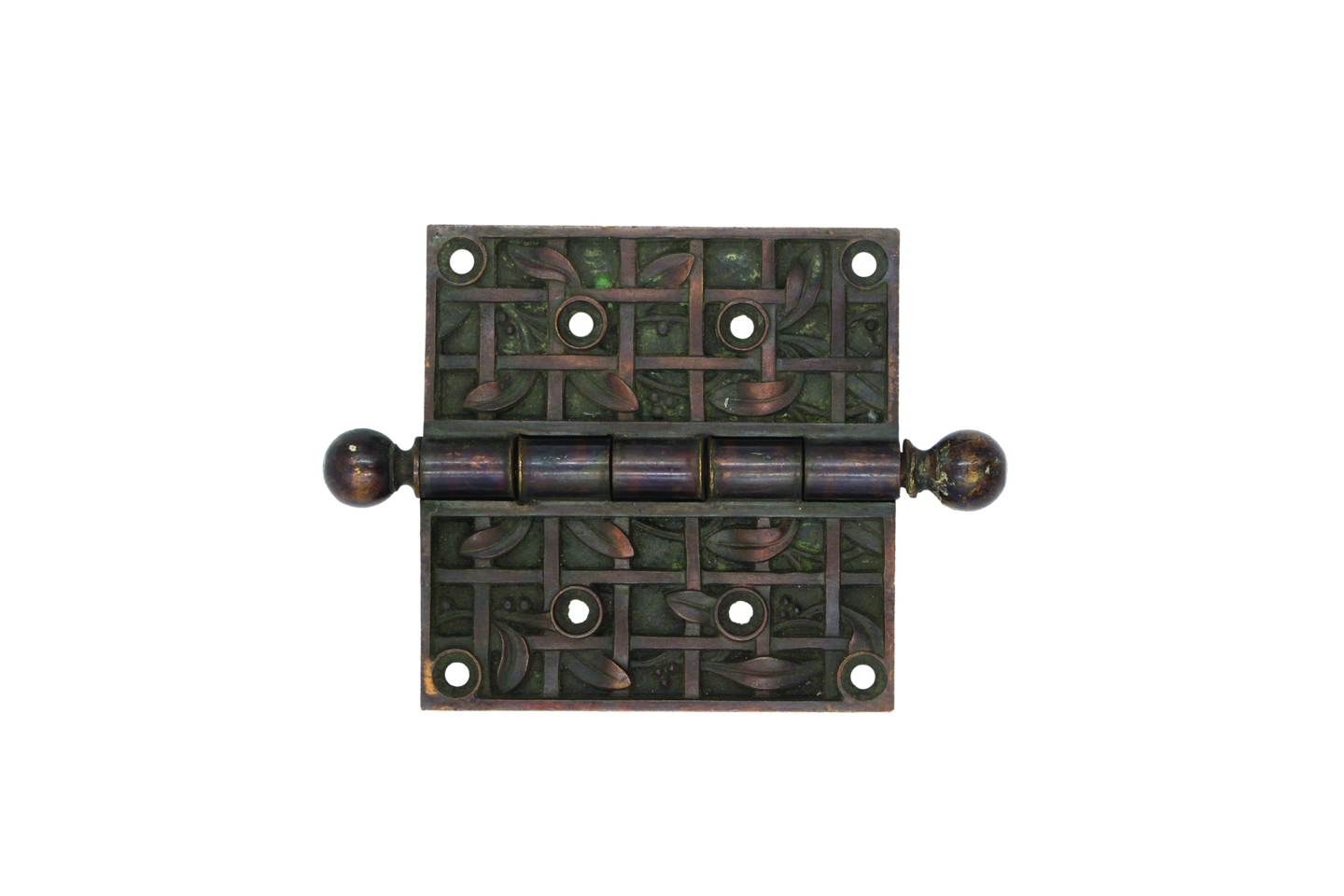

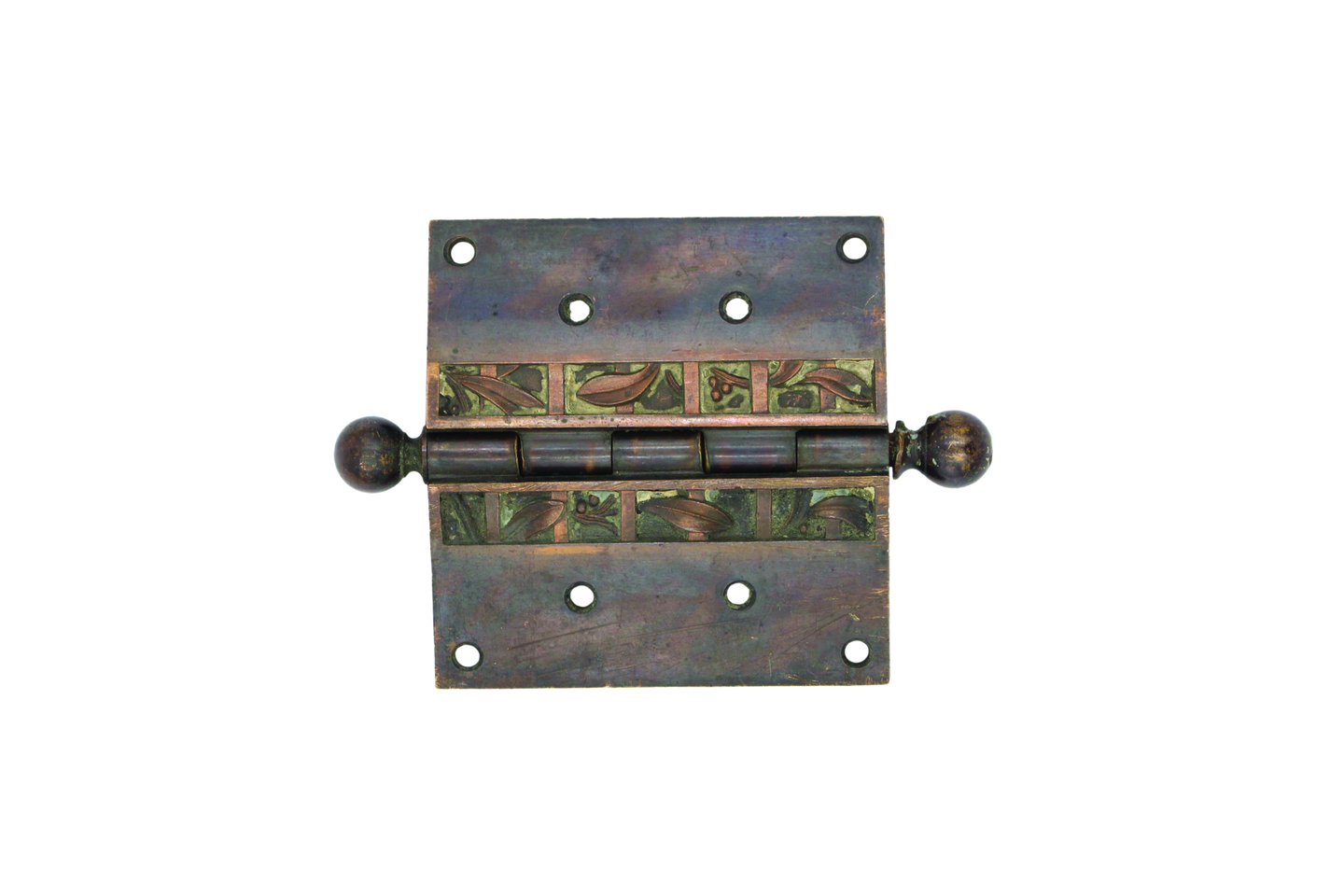

In the North American context, hinges were obtained from England into the 17th century, until blacksmithing emerged as a trade and strap hinges were forged locally. One particular blacksmith famous for his hinges was Charles Hager. After emigrating from Germany in 1848, he took over the blacksmith shop in St. Louis, and the company began manufacturing wagon wheels and hinges for wagon doors. Hager evolved that design into the T-hinge (Figure 3, above), then the ball bearing hinge c. 1899. The butt hinge emerged in 1900 (Figure 4, above). Recessed into the frame and the door leaf, it took over as the hinge style of choice.

Hinge Types

Early hinges had two “knuckles.” The “pintle” is a fixed pin attached to the frame, over which the “gudgeon” (attached to the door so it can be lifted off) is placed. Paumelle hinges are similar, but the pintle is attached to the door and fitted down into the gudgeon. A special configuration of the pintle, the gudgeon, and the paumelle is the olive hinge, where the pintle and gudgeon are enclosed and form an olive shape. As the hinge evolved, it came to have three parts: the flanges, the jamb, and the stile. The stile has gudgeons and a pin, which threads alternate gudgeons and connects the two flanges. The hinge can be “loose,” as in removable, or “fast,” as in fixed. The pin can have no detail, being flat on the ends, or it can have an array of decorations, such as ball, acorn, or finials on either or both ends.

The strap hinge evolved to have two knuckles, and more later on. The more knuckles, the less strain on each one. The T-hinge is differentiated from a strap hinge by a jamb flange that is taller than the stile flange. Both strap and T-hinges can have simple or elaborate stile flanges mounted exposed to the door. The later butt hinge, so named because it is mounted where the door abuts the jamb, is mortised into both the door and frame, with just the knuckles showing.

Originally, hinges were placed two to a door and were sold in pairs because doors never used just one. In the early 1950s it was understood that the more hinges on the door, the less strain on the hinge, and the practice of placing a third hinge at the midpoint between the other hinges became standard. This evolved into the industry of ‘one and a half pair butts.’

With the understanding that more knuckles experienced less strain and that more hinges better supported heavy doors, eventually the continuous or “piano” hinge was developed to support a large leaf.

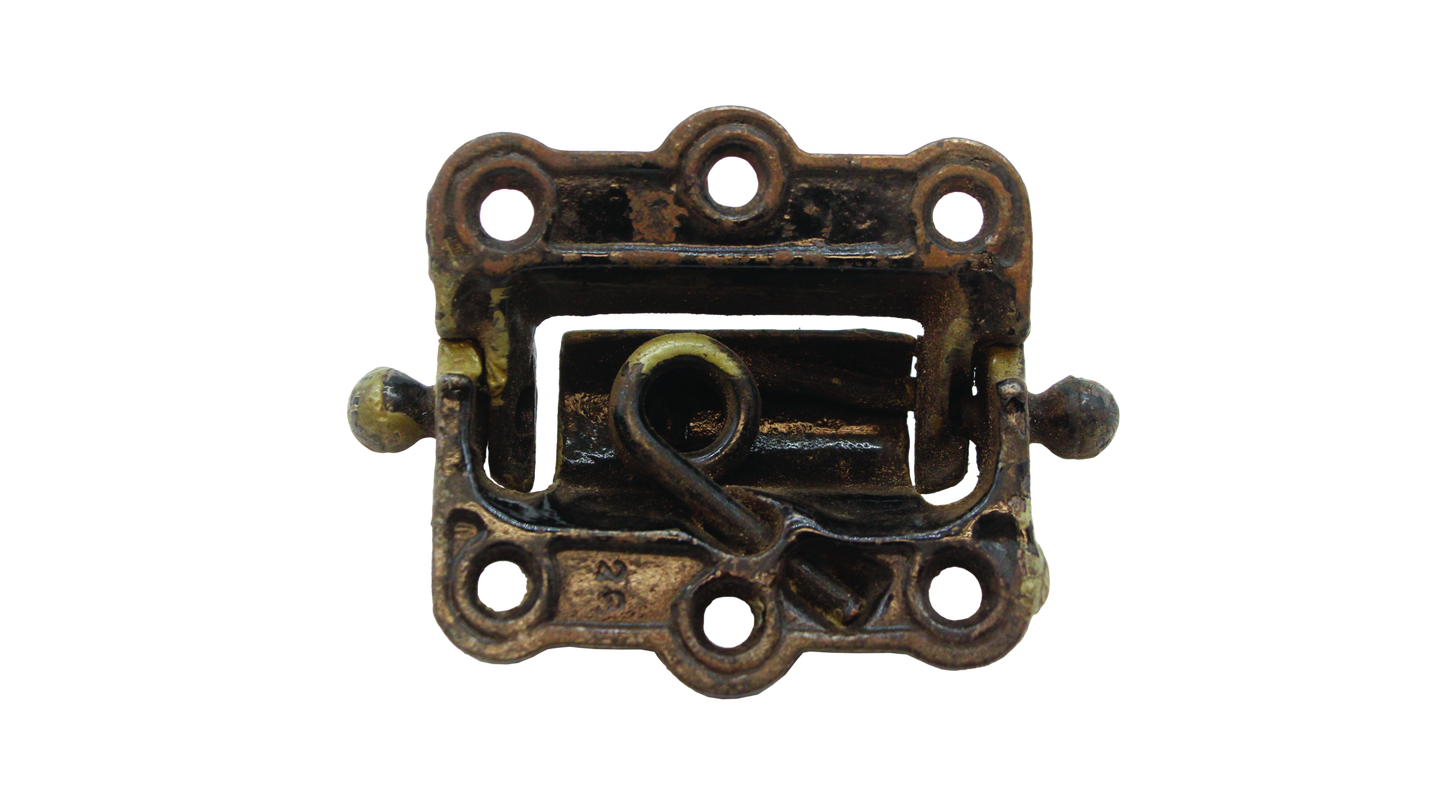

The knuckles began as plain bearing—metal on metal. Ball bearings evolved to make the door operate more smoothly. Spring hinges (Figure 5, next page) evolved as a way to automatically close the door but were suitable for only lighter screen doors. Rising butt hinges are a specialty type, where the door leaf is lifted about a half inch as it opens, to clear carpets or uneven floors.

Hinges can be highly decorative in their exposed parts. When the hinge moved to the butt style, the decorative nature continued through the 1800s and early 1900s, but has gradually been phased out and replaced by the utilitarian style used today.

Failures and Repairs

The most prevalent problem with hinges is when the hinge is loose. This is typically caused by the loss of a screw, or failure of the wood to support the screw. Screws should be replaced immediately, since the loss of support of the flange can cause racking of the hinge and damage to the knuckles. Where the cause is wood failure, the screw hole can be filled with a mixture of permanent woodworking glue and sawdust. Once dry, new screws of a matching slot configuration can be placed.

Another common problem involves the pin that connects the knuckles. Pins that drift out of position can be tapped back down into the knuckles using a mallet.

If the knuckles have failed, determine the cause of the failure. The door may have been mishandled, such as being wedged open. Hinges can possibly be placed in a padded vice and manipulated back into position. However, if the weight of the door is too great, additional hinges may be required, or they may need replacement with a heavier duty hinge.

Where hinges are lost or damaged beyond repair, replacements may be found at antique stores and architectural salvage companies. In an extreme case of significant properties, hinges can be recast by making a mold of one of the existing. Forged hinges can be replicated by iron workers using traditional techniques.

The operation of the door very much depends on the hinge. Historic doors typically had all hardware matching in style and material, consistent with the period in which the doors were installed. Hardware should be repaired first, to maintain the historic fabric. If that is not possible, replacing hardware should always be done in kind, so that the appearance of the door, typically the first part of the structure that is encountered, is consistent with the whole of the building.

Susan D. Turner is a Canadian architect specializing in historic preservation of national registered buildings. She is the Senior Technical Architect for JLK, a woman-owned business specializing in the repair and preservation of historic buildings. She can be reached at sturner@jlkarch.com