Product Reports

Exterior Lighting for Historic Buildings

Manufacturers of exterior lighting fixtures are making adjustments to meet market demands while maintaining historic designs.

By Annabel Hsin

Historically styled lighting fixtures remain popular for both new and restored buildings, but manufacturers today face a number of challenges. One is the need to cut costs because of changes in the economic climate, and another is keeping up with new technology. Lighting manufacturers are constantly learning ways to meet these challenges while maintaining historic design integrity.

"Cost issues have come into play more during the recession resulting in the 'value engineering' of designs or even decisions to replace period replication with stylistically oppositional designs," says Gary H. Behm, president of St. Louis, MO-based St. Louis Antique Lighting Co. "Most historic projects start with budgeting for accurate replications and would like to use them; in the end, many of these projects look for ways to save costs and changing 'exact replication' to the phrase 'similar to' is not unusual.

"The standard ways to cut cost for replications are using cheaper materials and simplifying ornamentation," says Behm. "For restorations, which is primarily labor, the cost-savings usually come from avoiding the cost of total refinishing or using a 'faux' finish as opposed to providing the original patina."

Herwig Lighting in Russellville, AR, helps clients save on tooling charges by using its standard patterns, and there are many options to choose from as the firm has been fabricating fixtures since 1908. "We'll try to use as many of our standard parts as possible," says president Don Wynn. "It may not be an exact fit when compared to the original but they would save several hundred, possibly thousands of dollars."

Doreen Joslow, principal at Ivoryton, CT-based Scofield Lighting, says her company also uses a similar technique for reducing costs. "It's customization instead of 100 percent custom," she says. "A lot of times, we'll use a new mirror in place of a pewter reflector, plate glass instead of hand-blown glass or switch out the brackets. We also hide all the electrical hardware that could possibly take away from the authentic historic appearance."

In spite of the challenges, design is still the most important goal among suppliers. "The most difficult challenge is making beautiful designs that perform technically and last out in the elements," says David Calligeros, founder and president of Remains Lighting in New York City.

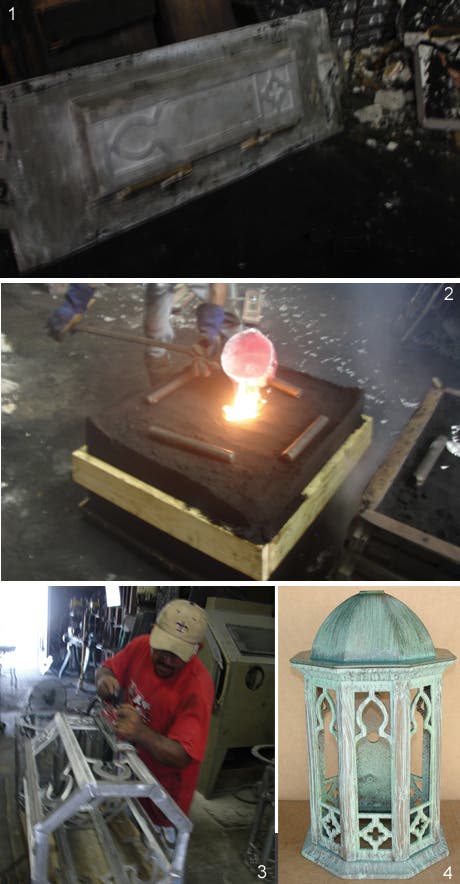

Behm notes that since the late 1800s through the early 1900s most exterior light fixtures were fabricated of non-ferrous metals, such as bronze, brass and copper, and some were made of cast iron. They all used glass diffusers or globes, usually in opal white, frosted or etched clear glass. Due to the cost and weight of these heavy metals, aluminum has become a popular material for use in replication. It is about one third the weight of bronze or iron so the per-pound price is considerably less. "Aluminum works fine with painted finishes but not for the traditional hand-relieved antique brass, bronze or copper finishes, which are so popular with conservators, preservationists and architects working on historic projects," says Behm.

Herwig Lighting was one of the first companies to switch to aluminum and gradually stopped casting in bronze. "We've used aluminum in place of bronze or copper on many occasions," say Wynn. "The main difference is that bronze is a natural finish that will gradually turn patina. We'll duplicate that process using paint. Painted aluminum doesn't change like bronze but the surface will last for years with periodic touchups. We have fixtures from the 1950s that are still standing today."

Aluminum also runs into problems in locations with strong acid, such as street light poles in the northern states. "I'm very careful with locations near the ocean even though we use resistant aluminum alloy when we cast fixtures," says Wynn. "Our standard alloy #356 has less iron so it's more resistant to the atmospheric salts and chemicals attacking the metal."

Scofield, on the other hand, prefers heavy-gauge copper for its fixtures fabricated for New England locations.

Meanwhile, the lighting industry is moving toward LED (light-emitting diode) technology.

"Keeping up with the rapidly changing technological environment is challenging even for lighting designers and engineers who specify these products regularly," says Behm.

The goal is to integrate LED sources into historic lighting, which is a difficult task since most traditional fixtures are developed with a visible light source and exposed LEDs are jarring, notes Calligeros. "To ensure that the aesthetics are in keeping with a historical vocabulary, we essentially have to obscure the point-source of the light behind frosted glass or in a white shade," he says.

"LEDs are narrow spectrum sources that approximate full-spectrum sources by mixing red, blue and green lights or by 'doping' blue light LEDs with phosphors, which is similar to a fluorescent light. Neither of these are as rich as incandescent or live flame but with careful arraying and mixing, we can achieve a decent uniform illumination pattern."

While Scofield Lighting has not experimented with the new technology, both St. Louis Antique Lighting and Remains Lighting offer LED lighting on a project-by-project basis. "Achieving higher light levels for outdoor lighting is one of the challenges in the exterior LED industry," says Behm. "We recently had a historic project where the LEED requirements dictated very low light levels for the wall brackets on a federal court house. The difficult access to these fixtures and low lumen requirements made the use of LED lamps a good choice for the application."

Wynn recalls that he attempted to develop a LED fixture for Herwig Lighting's permanent collection but was unsuccessful. "I had a sample made a year ago but it just didn't work out," he says. "The drivers had to be adjusted in order to regulate the heat emanating from the light fixture. As the heat in the fixture built up, it would drop the lumens in the fixture to compensate for the heat and consequently we were losing light. I want to make sure that the technology progresses to a point where they are dependable before we offer LED fixtures."

Lighting manufacturers also note that planning for lighting early in the project can be an effective cost-savings measure. "Advanced planning opens the widest selection of choices and costs," says Calligeros. "Most high-quality lighting is made to order and can take up to 18-20 weeks for delivery. 'Off-the-shelf' product is generally less than top quality. Custom lighting demands even more advance planning. Waiting until the end of the project to think about the exterior lighting schedule means few choices and great expense, or settling for cheap, ill-fitting compromises."

"Lighting comes in at the end of the project even if it is in the specs," Joslow says. "If the clients are good at planning and keeping within the budget then it all works out. If they run out of money, we'll do a second round of lighting specs, which is really frustrating because it's really better to buy once and buy well. In the long run, it serves the client better."