Product Reports

Early-20th Century Cornice Replication

It’s worth noting that PRESERV was instrumental in the design, fabrication, and installation of the cornice, seeing the work through every step of the way as the general contractor and builder for the project.

Cornices come naturally to tall, turn-of-the-20th-century buildings. For Louis Sullivan, the acknowledged father of the skyscraper, “the chief characteristic of the tall office building [is that] it is lofty,” and an attic story and distinct cornice emphasize this loftiness. Unfortunately, loftiness was at a low ebb in 2013 when owners decided to restore The Hadrian, a 10-storey, 1903 apartment building on New York’s upper west side.

Recalls Guenther Huber, president and principal of Ornametals Manufacturing, LLC., based in Cullman, Alabama, “The architects, Jan Hird Pokorny Associates, Inc., were very into the details of the original cornice appearance, but when they called us in, there was nothing there.” Indeed, while the 1903 galvanized sheet steel remained, rust had perforated it with pin holes, all cresting was gone, and the surfaces were nearly devoid of stamped zinc ornaments. “When I saw how the remaining ornaments, the old lion’s heads, were only hanging by wires, I wouldn’t even walk underneath it!” he exclaims. “So this is a 100 percent replica of how the cornice looked in the beginning.”

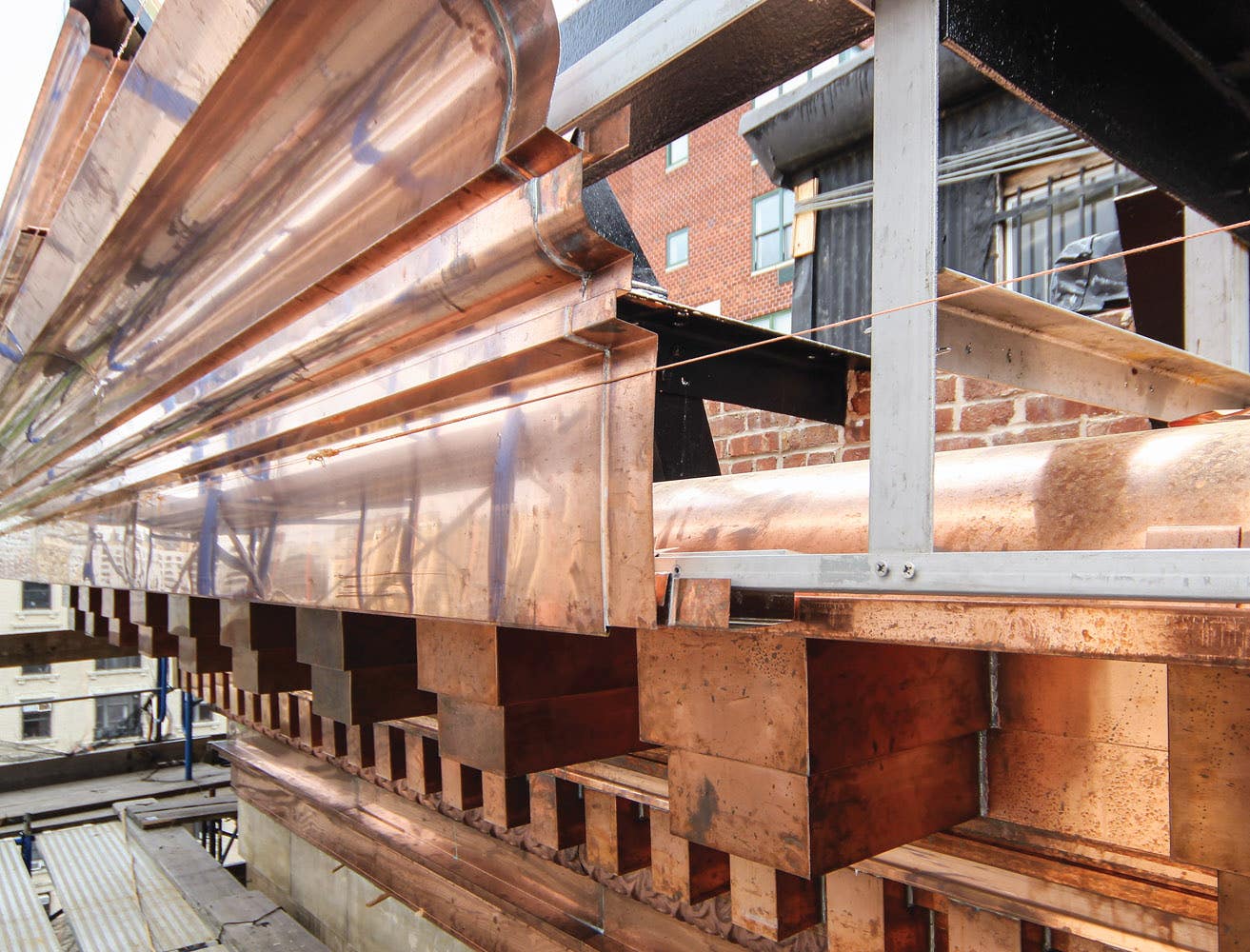

While the new work is meticulously accurate, the construction, though traditional, is a big improvement on the original. “Before they used metal sheets as a base, and then wired on the ornaments.” Instead, Huber’s company needed to have fastening points every two feet, so they designed a whole under-construction in stainless steel. “Because copper moves, you always need to think about expansion,” he explains, so to do this, the full cornice is composed of many smaller panels. “It’s all cleated together, so that each panel can move, totally independently.”

Huber, whose family has been in the metals business in Germany since the 1820s, says the method has a long history there and in France. “You have the back plate on, then the metals get slid together and cleated in, so you can’t see it.” Each panel is about 24 inches high he says—perhaps 30 inches at a maximum—and all of the panels, just clip together. “It’s basically the same method you would use to install a standing-seam roof.”

The supporting under-construction is anchored to existing steel brackets extending out of the wall, and adds stainless steel strips to hold fastening clips every 12 inches to 16 inches for wind lift and the like. “You need to deal with cornice work the same way you deal with roof work,” reiterates Huber, “and it needs to be wind-proof to 150 miles per hour. In New York City you can have winter storms or even hurricanes.” He adds that the stainless steel probably isn’t even necessary because no water can enter. “Plus, the whole cornice is vented. There are weep holes on everything, so should any water come in the back side, it dries out immediately.”

Turns out, the panel-and-cleat method has advantages beyond allowing for expansion in the complex, 14-foot-high cornice. “Installation was the easy part,” says Huber. “Because the length of each panel is around 6 feet, and the width is 2 feet to 3 feet, the weight is not so much, so it is very easy to handle in scaffolding.” The actual installation was carried out by a New York company, Preserv Inc., with initial assistance from Huber’s team. “Everything went so smoothly because the New York contractor for the under-construction followed the drawings precisely and knew exactly how to do it. It all fit together like it should.” The cornice runs around three sides of the building for about 220 feet and took just three weeks to install; planning and fabrication was about three months.

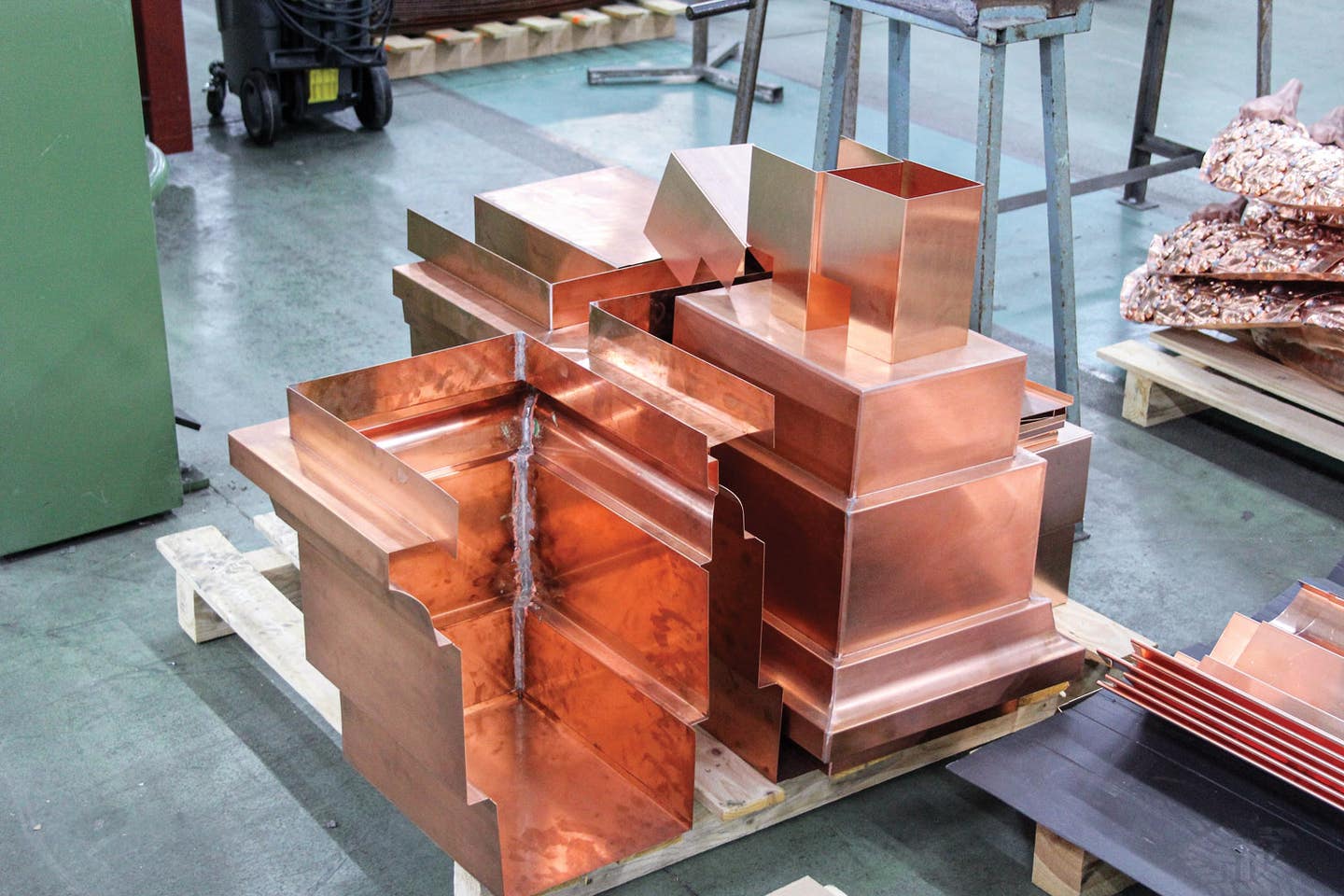

Because the cornice required a lot of large, pressed-zinc parts, Huber partnered with VM Zinc (now VM Building Solutions) located in Bagnolet, France. “I fabricate here in Cullman, Alabama, in Germany, and in France. When I have a big project, like the Kansas State Capital building in Topeka, I fabricate in all three countries, so I’m always commuting on planes!” Fabrication is all traditional sheet-metal methods with bending brakes and related techniques. “When you look at a garland, for instance, it’s not one single piece but pieces of leaves put together. Then we put a back plate on, rounded and bent to the leaves. That’s how you did it 100, 120 years ago.”

As far as materials, Huber says they don’t often settle for light, 16 oz. copper. “When we do work like this we go with 20 oz. copper, and even up to 24 oz. copper, especially for fabricating ornamental pieces that require deep stamping. For this project, we went with 0.7 mm thickness, which is pretty much 20 oz. copper, and 0.8 mm.”

In the end, the cornice cost a little bit more in fabrication, says Huber, but it was so much faster in installation. “We could prove to the owner, when you do it like this, you have not only a much better product but a cornice that will hold up for the next 150 years.”

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.