Windows & Doors

Cold Mountain Custom Window Demonstrates the use of copper as a fenestration option.

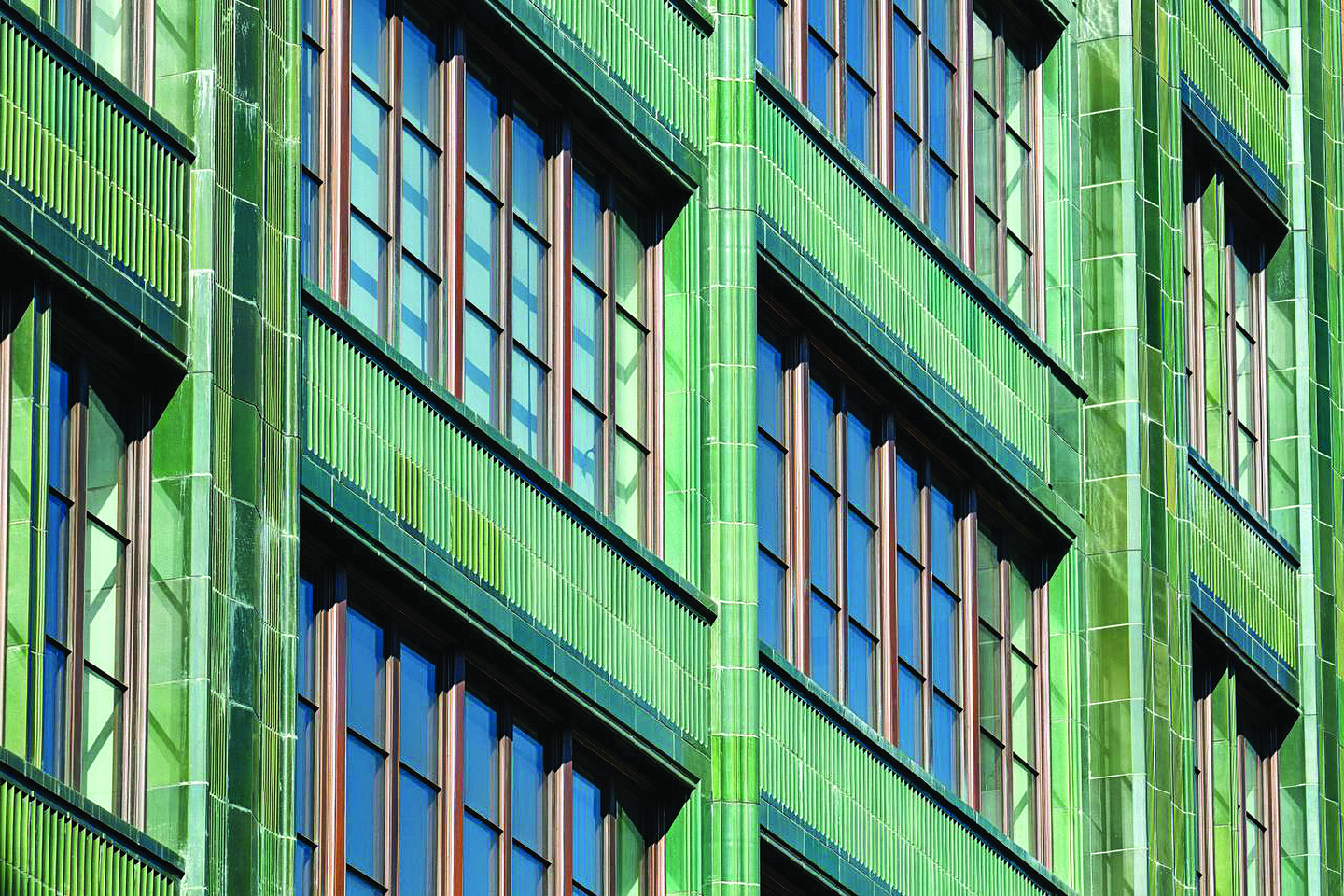

Historic architecture abounds in the eclectic West Side New York City neighborhood of Chelsea, and rising among the mix of 1850s row houses, former factories, and trendy art galleries is a new, two-tone, Art Deco-inspired building right in step with local color.

“The front façade of The Fitzroy is big on copper,” says Tim McFadden, director of sales and distribution at Cold Mountain Custom Window LLC, in Putnam Valley, New York. His firm works with architects and contractors across the United States to distribute the product line of Mixlegno Group, an Italian manufacturer known for high-level craftsmanship and unique window and door systems, such as those used at The Fitzroy. “It’s all high-end,” says McFadden, “so it works well with traditional building projects.” In fact, Mixlegno has built an international reputation for combining wood and sought-after metals, such as bronze, and the windows at The Fitzroy, which are copper on the outside, white oak inside, are a prime example. Perhaps it should be no surprise coming from a company based near Venice, with its traditions of handwork and historic buildings.

What’s more, in the hands of design team Roman and Williams and developer JDS/Largo, the pinkish-orange tones of natural copper and the intense verdigris of its aged patina comprise the striking central motifs of The Fitzroy. The exterior is covered in deep, jade-green, glazed terra-cotta cladding that is accented by rich copper details in the windows and wide spandrels. Because of the way it’s treated, the copper has a dynamic character, progressing from warm and even to variegated as it ages. Copper is an important theme in the interiors too, explains Andrea Zorzi, president of Mixlegno. “Bathroom plumbing fixtures and tubs are often all in copper,” he notes, “a kind of twin with the windows.” Kitchens, too, feature copper stove hoods and lighting fixtures, with elements repeated outside and inside throughout the project.

However, making copper windows for this project takes more than some surface sleight-of-hand. Explains Zorzi, “Because copper is very soft, forming sheet copper would not be precise and have any design in the final profile. So, we’ve found a way of fabricating an extruded base, 2mm to 2.3mm thick, in a very sophisticated design on the exterior.” He says it’s unique, not something standard in the market, “and we designed it right for the architects.”

Nylon clips attach the extruded profiles to the wood sash and frame, so the two materials will not be in direct contact, but separated by 3mm. “This allows air circulation between wood and metal, so the wood seasons naturally and prevents wood deterioration.” Moreover, this technology allows the two materials to naturally react to environmental thermal changes without conflict between the differences in wood expansion and metal expansion.

When all the parts are welded together—“with joints basically invisible,” says Zorzi, “because they’re welded from behind, then ground”—everything is cleaned by hand. Then they apply wax to the copper outside as temporary protection to keep it natural. “This allows the copper to oxidize over time and, in years, change color. So it’s a unique, very sophisticated aesthetic.”

No less sophisticated is the window glazing. “It’s double laminated glass,” explains Zorzi, “laminated glass on the outside, then space bar, then low-e laminated glass on the inside.” He points out that laminated glass is particularly well suited to urban projects because, being layers of dissimilar materials, it dampens sound transmission.

Notably, the glass is one window component specifically engineered not to include green. “Italy is known not only for their craftsmanship but also for their glass,” explains McFadden. “The standard there is low-iron glass, which is ultra-clear—no greenish tint—and something you pay a premium for here in the United States.”

The scores of unique windows are a defining part of the building facade. “There’s a combination of operable and fixed units,” says Zorzi. “Sometimes operables separated by fixed units, and both in-swing and out-swing casements.” He recalls that for delivery they divided the project into three steps, starting with floors 10, 9, and 8 as the first shipment, followed by 7, 6, and 5, then down to the first floor as the last shipment.

Inside, all the windows are oak, as specified by the architects for a variety of reasons. “It’s a very high-quality wood,” explains Zorzi, “mechanically, very strong and stable, and it’s also a sustainable wood.” He adds that the oak is also quarter-sawn, a cut that maximizes stability and beauty.

In fact, though the window interiors are protected by a finish, it’s neither a clear varnish nor a conventional paint. “In Italy, we call it natural paint,” he says, “not a very heavy, colored paint but a thin coating.” The goal is to still see and feel the grain. “With such a beautiful wood, it’s a shame to cover it over.”

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.