Product Reports

Cleaning Stone Buildings

There are several reasons to clean a historic building. It can be necessary to remove soiling, which is causing on-going deterioration of the stone. Cleaning the stone and mortar joints can be necessary for understanding the original materials for appearance matching and documenting the condition of repairs, stone, and repointing mortars. Localized cleaning can be necessary for prompt removal of graffiti before it attracts other graffiti. If cleaning is being requested for purely aesthetic reasons, the benefits of cleaning should be seriously weighed against the potential harm cleaning could inflict on the building. One often-overlooked option is not cleaning the building at all.

Regardless of the reason, the building owner should carefully consider first, the advisability of cleaning the building at all, and second, how to perform the cleaning to be effective yet gentle, leaving no damage or conditions behind which would lead to further deterioration of the building. With all historic buildings, the goal of cleaning should not be a “like-new” appearance. The patina of age should be left behind, to tell the story of its history. Merriam Webster’s definition as “a surface appearance of something grown beautiful ... with age or use” fits the context here.

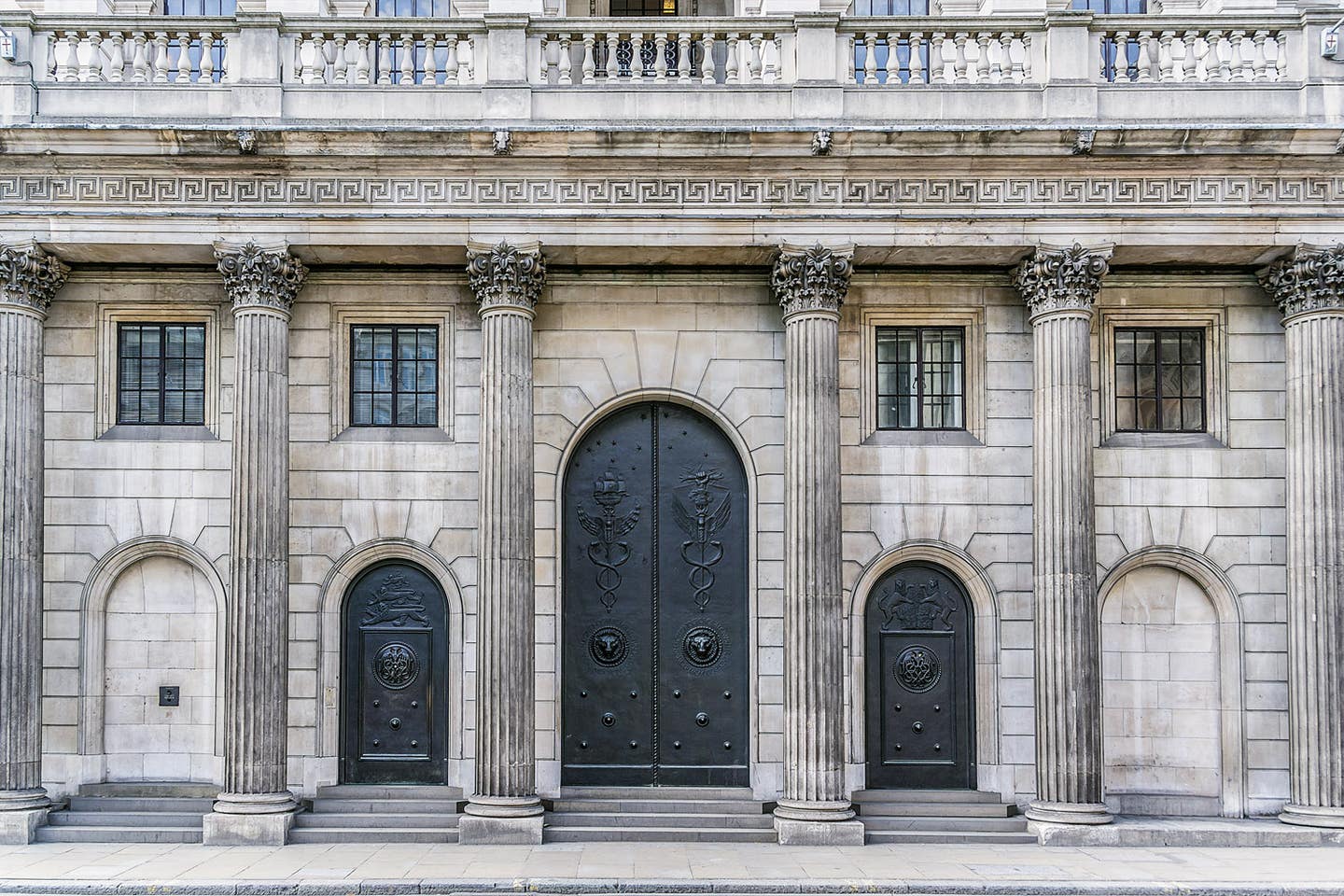

The first step is to identify the types of soiling. Different stains require different approaches. Stains can occur through maintenance and use, hand soiling, and wax build-up, for example. Some staining is caused by moisture issues. Various sources include roof leaks, broken gutters, and downspouts, plumbing issues on the interior of the building close the interior face of the wall, dripping window air conditioners, or condensation in the building envelope, making its way from a warm moist interior to the breathable exterior and depositing efflorescence. Efflorescence is a white chalky patchy crust caused by moisture that picks up solubilized mineral or gypsum; as the moisture evaporates on the surface of the stone, the residue is deposited on the surface. Stone that has been kept moist or habitually salted may have permanent dark stains. Stains can be comprised of chemical damage from previous cleaning campaign, from a bleached appearance to one of patches and streaks. The presence of bronze or copper elements adjacent to stone can oxidize, and rainwater carries the solution onto the stone causing green staining.

Beyond moisture staining, moisture can attract biological growth, from bacteria to algae to fungi to lichen to mold. Some buildings are known for their ivy-covered appearance, but vines and plants have “fingers” and roots which attach to the stone and dig into any fissure to take hold. Water channels into the crevices and forms ice, which fractures (“ice jacks”) the stone. As roots grow stronger and thicker, they too will force the stone and mortar apart, and direct water inside, further exacerbating the cycle of ice jacking.

Graffiti attracts more graffiti; cleaning eliminates the graffiti artists’ rival claims for the building. Graffiti can be surface applied or penetrating, depending on the medium used: permanent marker, to sharp instruments, or various paints. Because of the isolated nature of the stain, removing the graffiti may leave it just as visually prominent by the shadow of cleanliness left behind.

What is the stone?

It is important to understand what materials you are cleaning. Natural stone is either siliceous, a durable stone such as granite, slate, or sandstone comprised of silica or quartz particles, or calcareous, a relatively delicate stone composed of calcium carbonate. The polished or textured nature of the finish, and porosity and chemical composition of the stone affects the results of cleaning. Some elements of the façade may also be materials made to look like stone, for example terra cotta, cast stone, or pressed metal. Further, the selected cleaning solution for stone may be detrimental to adjacent glass, steel, aluminum, or other types of stone. These materials also need to be understood and protected.

Stone Cleaning Methods

There are three basic categories of cleaning, as explained below. Most methods require site protection to contain overspray, to prevent damage to adjacent structures, to collect aggregate and/or runoff, and to prevent nuisance complaints from adjacent property owners. If using an abrasive system, there can also be limitations of reach for hoses, or concerns for noise generated, which should be examined when making a final selection.

Water based cleaning uses water to soften the soiling to make it easier to remove. Some methods include twenty-four-hour water mist (soaking), low to medium pressure washing, steam, or high pressure washing. While water is typically the gentlest means to clean, it could solubilize gypsum or alabaster present, or saturate deteriorated masonry. It could infiltrate non-weather-tight windows and damage interior finishes, and cause rust on internal anchors. Wet cleaning should never be performed when there is any threat of freezing weather of frost.

Chemicals cleaners are acidic or alkaline solvents which dissolve dirt and suspend it in a solution, either water or organic chemicals-based liquid. Detergents surround and remove dirt which can be rinsed away. Detergents are less harmful for workers than chemicals, as they are non-flammable, and can be biodegradable. Both can be applied as a spray, with higher concentrates of chemical used with a scrub brush or in a poultice in areas of higher soiling.

Abrasive cleaning methods involve combining a granulated media into a pressurized hose, with water and/or air. There is a plethora of devices with which to apply media ranging from crushed walnut shells, to impregnated sponges, to a variety of grit particles which range in size, hardness, and sharpness. Abrasive cleaning got a bad reputation with early sandblasting campaigns that caused a range of damage ranging from removing surface texture and detail, to opening the pores of the stone, to exacerbating weathering. Aside from the selection of the device and the media, the outcome of this process varies, depending on consistency of application pressure and pattern, the level of pressure used, and the skill and fatigue of the operator.

Lasers use a difference in energy potential between the stone and the soiling to remove dirt. The laser sends pulses of infrared light onto the stone, which heats up the dirt instantly, causing a rapid thermal expansion, which in turn causes the dirt to lift off the surface. In some ways, dry ice, or CO2 cleaning is like the laser, in that it uses pellets of frozen liquid CO2 (-78 to -103°F) and propels them against the stone surface and causes an initial thermal shock to the surface dirt, freezing and shrinking it. It is like abrasive cleaning, in that the dry ice pellets impact the surface, they sublimate into a mini explosion when the frozen liquid changes to gas. The physical impact of that same pellet breaks up the brittle frozen dirt and removes it.

While it may seem counterintuitive, any liquid cleaning methods should proceed from the bottom up. This prevents cleaning solution streaking a dirty wall below, which does not happen if the wall is clean and maintained in a wet condition.

Cleaning Methodology

When beginning a cleaning project, proceed with caution, and in an orderly process. Start with surveying the building to determine if it has been cleaned before, if any paint coatings are original, if there is any localized damage, and to document the conditions and locate them on a drawing. Frequently the drawing effort will bring to light the patterns of soiling and/or wetting. Compare survey drawings to plans showing room functions, mechanical systems, and plumbing piping. Correlation of the uses and systems to the façade patterns frequently speaks to the cause of these stains. Once the cause has been identified, eliminate the cause by fixing the roof, patching the pipe, controlling moisture in the building, eliminating the air conditioner units, or other solutions as applicable.

Determine the type of the stone and its condition, along with the condition of the mortar.

A particular concern for a cleaning program is the starting and stopping points. Cleaning should never be performed on the front façade first. The method should be proven successful before it is implemented on significant facades. Where there are budget concerns, performing consistent cleaning on the entire structure may not be affordable, In that circumstance, serious consideration should be given to not undertaking any cleaning campaign on the building at all.

Once all the above is known, research appropriate potential cleaning methods recommended for the stone type. For each selected cleaning method, perform physical testing in a discreet location of the building, such as an areaway, back lane face, inside parapet.

Mock-ups should be ideally performed a year in advance, so that the samples can weather, and any deleterious effects can be observed in the spring. If a contractor has not been onboarded. An experienced masonry cleaner can be hired for the purpose. Or manufacturer’s agents for the various cleaning systems can be enlisted to help. While performing cleaning tests, the parameters are tightly controlled; controls on site should deal with hot weather requirements, minimum temperature requirements, and worker comfort, protection, and fatigue. For water cleaning, a variety of water pressures, distances to the stone face, and uses of non-ionic detergents should be mocked up. For abrasive cleaning, different aggregates can be tested, administered at different pressures, and at different distances. For chemicals, the dwell time and concentration, as well as different types of chemicals can be sampled. All testing should be recorded as to the location of the sample, with photographs taken before and after, and notations of the materials variables involved, with an opinion of efficacy.

Prequalifying contractors with relevant building cleaning experience, and with crew who are also individually experienced, will go a long way in achieving success. Once the project goes into the field, project success is entirely dependent on capable trades performing the work. A lot of cleaning processes are safer with workers wearing full Tyvek suits, and possibly a respirator-type mask, which can cause workers to overheat. Ensuring sufficient water breaks and rest periods will assist in workers maintaining the established distances, pressures and protocols documented in the test trials.

The subject of stone cleaning is extremely broad. Each project is unique, and has its challenges, be it materials combinations, a cramped site, deteriorated masonry, and the like. A stone conservator or historic architect well-versed in masonry should be retained to develop any stone cleaning process, because many systems can cause irreparable damage if performed inadvisably or incorrectly. Due diligence in planning and execution is critical to the preservation of the structure.

Poultice

During cleaning, if the cleaning method does not address stains, a poultice can be used. A poultice provides a longer dwell time of the cleaning material such as water, detergents, solvents, or other chemicals. A poultice consists of inert material, such as diatomaceous earth mixed with the cleaner, the gentlest of which is water. Once thoroughly mixed in a clean plastic container, it is applied to the stone with a plastic spatula or scraper in an even coat and then covered with plastic. As the substrate absorbs the moisture, the cleaner is drawn into the pores where the stain is. Once the plastic is removed, the poultice dries out, wicking the moisture back out of the pores, taking the soiling with it. The poultice absorbs the chemicals and contains the dirt. Once the poultice is fully dry, the crust can be removed with a plastic scraper and swept away, leaving a cleaned surface, once rinsed.

As with all cleaning methods, a small area should be tested in an inconspicuous location and observed after a week once it is fully dry. If it is determined that the process does not bleach the stone, open the pores, or cause a negative chemical reaction, the poultice can be applied on the rest of the stain, if effective.

Resources

National Parks Service Preservation Brief www.nps.gov/tps/how-to-preserve/briefs.htm

No. 1 - Cleaning and Water-Repellent Treatments for Historic Masonry Buildings.

No. 6 - Dangers of Abrasive Cleaning to Historic Buildings

No. 38 - Removing Graffiti from Historic Masonry

Historic Scotland Technical Advice Notes www.historicenvironment.scot/archives-and-research/publications/?publication_type=42

TAN 09 – Stonecleaning of Granite Buildings

TAN 10 – Biological Growths on Sandstone Buildings: Control and treament

TAN 18 – The Treatment of Graffiti on Historic Surfaces

TAN 25 – Maintenance and Repair of Cleaned Stone Buildings

Susan D. Turner is a Canadian architect specializing in historic preservation of national registered buildings. She is the Senior Technical Architect for JLK, a woman-owned business specializing in the repair and preservation of historic buildings. She can be reached at sturner@jlkarch.com