Product Reports

Buon Fresco: Materials & Techniques

Buon fresco is true fresco, meaning it is a painting executed on a freshly plastered wall (fresco means “fresh” in Italian). There are also “untrue” frescoes – using lime water on a dry plaster wall, for example, which is known as fresco secco or dry fresco. But fresco is more than just a technique, it is a tradition, and to understand the medium you need to know something of its history, the ways it has been employed in great rooms and on facades and the vicissitudes of its practice over time – from rigor to decline to restoration.

Perhaps no other artistic medium calls to mind such specific imagery as fresco. For those who have been to Italy, it is likely that the majority of paintings they encountered on the walls of villas, palaces and churches were executed in buon fresco and, as with Classical music, many of the terms used in the contemporary practice of fresco painting are Italian. It was in Italy that the technique underwent a major revival beginning with Giotto’s master, Cimabue, in the 13 century, and it was there where it was revived again in the 20 century through the efforts of restorers and a singular artist named Pietro Annigoni. While marvelous frescoes can be found from our nation’s capital to monasteries in Russia, the paradigms are still those masterworks created in Italy in the Renaissance.

Many Americans flocked to Florence after the disastrous flood of 1966 to save what they could of frescoes being damaged by the receding waters (it was not contact on the surface with the water per se, but rather with caustic elements – including decomposed bones from monastic cloisters – leaching up through the walls that did the greatest damage); the reward for this service was the largest traveling exhibit of frescoes before or since, which came to the Metropolitan Museum in 1968. Many of these detached frescoes where removed and restored by the master restorer with whom I studied fresco technique, Leonetto Tintori. Despite vulnerability to such cataclysmic events as floods, one of fresco’s prime advantages is its durability. The reason the Sistine ceiling, for instance, could survive centuries of misguided restorations is precisely because Michelangelo’s pigments were so firmly bonded to their plaster.

Masterly and Beautiful

As the Renaissance painter and writer Giorgio Vasari suggests, it is the almost heroic character of working into the fresh plaster – meaning nothing can be corrected or erased without chipping off the plaster and starting again – that makes buon fresco “masterly and beautiful.” Fresco demands solid preparation, long hours and a bold, confident touch. It resists fussiness and rewards bravura.

The overawing impression of Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling is owed, in part, to the perfection of his technique, which took him some time to achieve as he moved down the chapel’s length over four years. But that perfection, which could only be realized at lightening speed, can only be seen up close and is unavailable to the audience 60 ft. below. This recalls Ruskin’s Lamp of Sacrifice and artistic effort made for god alone, but fresco has also been brilliantly put to very worldly uses, as Giulio Romano, architect and painter, did at the Palazzo Te in Mantua. There the frescoed gods feast in wanton reverie, while the audacious giants are crushed under the painted rocks set tumbling by Jupiter’s frescoed thunderbolts. It is just this capacity to transform walls into fictive worlds, earthly or divine, that recommended fresco to artists and patrons for centuries and, no doubt, it was also the fact that it was relatively inexpensive (due to the speed of execution) that made patrons favor it over more costly wall decorations.

Step By Step

The materials and techniques of fresco are simple enough: aged, slaked lime putty is increasingly more available to artists without the resources to make their own lime pit and fine, salt-free sand or marble dust are common.

The steps in the creation of a buon fresco are:

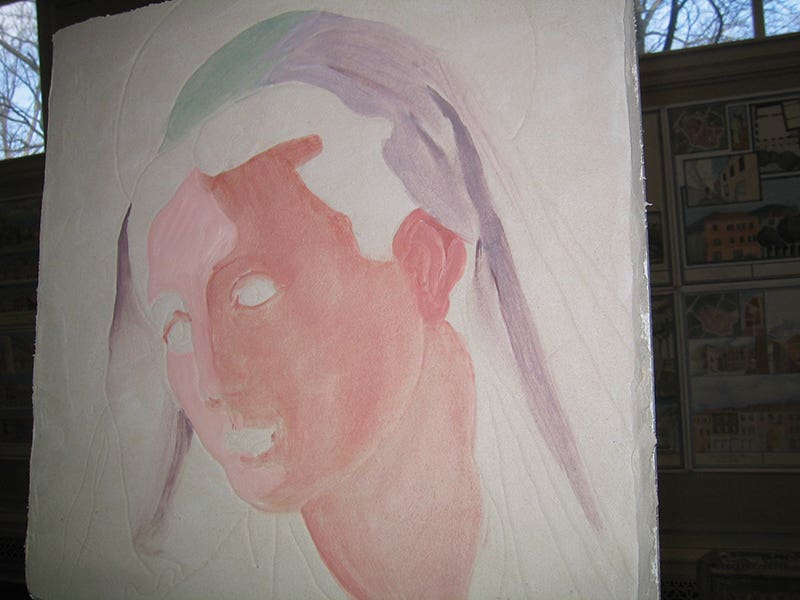

-The initial idea is invented, perhaps first by drawing, but eventually developed and described in some sort of painted color study (the bozzetto or small draft).

-A full size drawing, or cartoon, is made for each of the principle elements (figures, architecture, etc.). This will be progressively transferred to the wall over the course of painting.

-The number of giornate, or day’s painting, is defined: these are based on the artist’s experience of how much he or she can paint in the roughly eight hours available while the plaster remains “fresh,” or able to bond the pigments onto its surface.

-The wall is prepared with its base coats. The plaster is composed of aged, slaked lime putty and aggregate (sand, volcanic ash, marble powder). The first, the scratch coat, has the highest ratio of aggregate to lime. The second, the arriccio or brown coat, with a higher proportion of lime to aggregate, will receive a brushed outline drawing of the composition (known as the sinopia), in part to study the final effect in situ and partly to serve as a map of the various giornate.

-Beginning at the top of the composition, the first giornata is begun by applying that day’s intonaco, or finished coat (composed of equal parts lime and aggregate) onto a damp arriccio, over-plastering the size of the giornata. Within the first half hour or so of plastering, the corresponding part of the cartoon is transferred to the wall (by either pouncing through holes punched in the cartoon or tracing over the drawing with a stylus). As one plasters, the sinopia below is covered over.

-Painting is done with pigments adapted to fresco, and water. Each artist has his or her own methods and techniques, but generally one works from the broad forms to specific details and shadows.

-At the end of the day’s painting one bevel-cuts the edge of the giornata, scraping away the plaster beyond in preparation for the next day’s work; it is good practice to wet the wall of the next day’s giornata the night before.

Related Techniques

Sgraffito (from which we get our word graffiti) consists in scratching (sgraffiare in Italian) through a thin coat of lime or lime plaster to reveal an undercoat toned with a dark pigment (red, brown, grey or black).

Producing a high-contrast image, essentially resembling a woodcut, sgraffito may be more resistant to the elements in harsher climes than fresco. The technique was especially popular in 15 and 16-century Florence, and went through a major revival in that city in the nineteenth century.

Fresco Today

Fresco has undergone a mini-renaissance in the United States during the last few decades, thanks in part to the Metropolitan Museum’s fresco exhibit, Annigoni’s pupil Ben Long (who has worked in the States for 20 years or more) and many new schools of fresco. But in order for it to develop a full-fledged rebirth, traditional architects need to incorporate frescoes into the their projects for new buildings at the beginning of the design process, and in order to do this they need to both understand the medium and the ways is has served architecture historically. Ideally, as Ruskin, Michelangelo and Bernini would have it, architects should actually be painters and sculptors. Then painting and sculpture would find their home again in the mother of all the arts, architecture.

David Mayernik is a painter who works in oil, watercolor, and buon fresco, in addition to being a practicing architect and author of Timeless Cities: An Architect’s Reflections On Renaissance Italy (Westview Press); he is an associate professor at the School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame.