Product Reports

The Façade of a Building

When it comes to façade materials, bricks and terra cotta are two of the building blocks of historic design. These timeless elements have never gone out of style. Terra cotta, for example, has been making a comeback: Architects doing contemporary projects are specifying it because it is durable, fire-resistant and easily shaped into elaborate forms.

The trend, which started in Europe in the 1990s, has been picked up in the United States in projects like One Vanderbilt, a 1.6-million-sq-ft., 57-floor office tower under construction near Grand Central Station in Midtown Manhattan that’s taller than the Empire State Building.

“Terra cotta is green—it’s clay, water and fire,” says Bill Pottle, director of business development for Boston Valley Terra Cotta. “And you can do colorful custom glazes, which is what architects are asking for.”

Jess Ouwerkerk, project manager/surveyor in the Northeast for Gladding, McBean, agrees, adding that the company recently created terra cotta panels for 207 W. 79th St., a new-construction residential project in Manhattan.

On the brick front, thin is in. New-construction projects that want to convey an antique ambience increasingly are using this technique. “It’s a lot less costly than masonry and doesn’t require as much skill,” says Mike Gavin of Gavin Historical Bricks. “It’s installed in panels like tile. We are starting to tap into the potential on thin brick. I think demand will grow, especially on the commercial side.”

Brian Belden, vice president of sales and marketing for Belden Brick Co., agrees that the market for thin bricks is growing.

Here are some of the companies that are remaking the face of the façade industry.

Boston Valley Terra Cotta

Orchard Park, NY

One of only two major terra cotta manufacturers in the United States, the company was established by the Krouse family in 1981, following its purchase of Boston Valley Pottery which was founded in 1889. The original company made bricks and clay pots.The company, which is housed in a 185,000-sq.-ft. work space, has over 135 employees.

It combines historical handcraftsmanship with a modern infrastructure and 3-D modeling. Digital survey photos are scanned and Rhino software is used to create drawings, shop tickets and tool paths for the CNC machines to run. The company does hand and digital sculpting.

Boston Valley Terra Cotta’s first project, the restoration of Louis Sullivan’s Guaranty Building in Buffalo, NY, prepared it for work on other significant historic buildings.

The Woolworth Building in New York City

Recently, the company completed work on the Woolworth Building, a National Historic Landmark and a New York City Landmark. The Neo-Gothic icon was designed by architect Cass Gilbert for F.W. Woolworth. Opened in 1913, the 792-ft., 58-floor building, which the dime store magnate used as his company headquarters, is one of the 100 tallest in the United States and one of the 30 highest in the city.

Nearly a century later, Boston Valley Terra Cotta was hired by the masonry firm Nicholson & Galloway of Glen Head, NY, to repair the terra cotta on the top 30 floors, which had been bought by an investment group led by the New York developer Alchemy Partners for conversion to luxury condominiums. These Woolworth Tower Residences include a five-level penthouse.

“We went there to survey the building,” says Pottle. “Some of the pieces are very elaborate and technical.” Re-creating the terra-cotta pieces, which numbered 3,550, he says, was easy. Getting them to the building was a real challenge. “There were a lot of logistics to getting them to the 53rd floor,” he says. “New York City has stringent rules on truck sizes and timing and then there are OSHA rules for the scaffolding.”

The Jewelers’ Building in Chicago

Since 2016, Boston Valley Terra Cotta has been repairing and replacing the terra cotta on the Jewelers’ Building at 35 E. Wacker St. in Chicago. The 523-ft., 40-story building, which is in the city’s Loop, was co-designed by Joachim G. Giaver and Frederick P. Dinkelberg. Constructed between 1925 and 1927, it was one of the country’s tallest buildings. It’s on that National Register of Historic Places and has been designated a Chicago landmark.

Boston Valley Terra Cotta is particularly proud of the work it has done on Louis Sullivan buildings, including the Gage Building in Chicago and the Home Building Association Bank in Newark, OH. “We have been fortunate to work on some of the most iconic buildings in America,” Pottle says. “But the Louis Sullivan work holds a special place for us because that’s where we started.”

Gladding, McBean

Lincoln, CA

The family-owned company, founded in 1875, is one of two terra-cotta makers in the United States. In addition to terra cotta, it makes roof tiles, pottery, floor tiles and clay pipes.

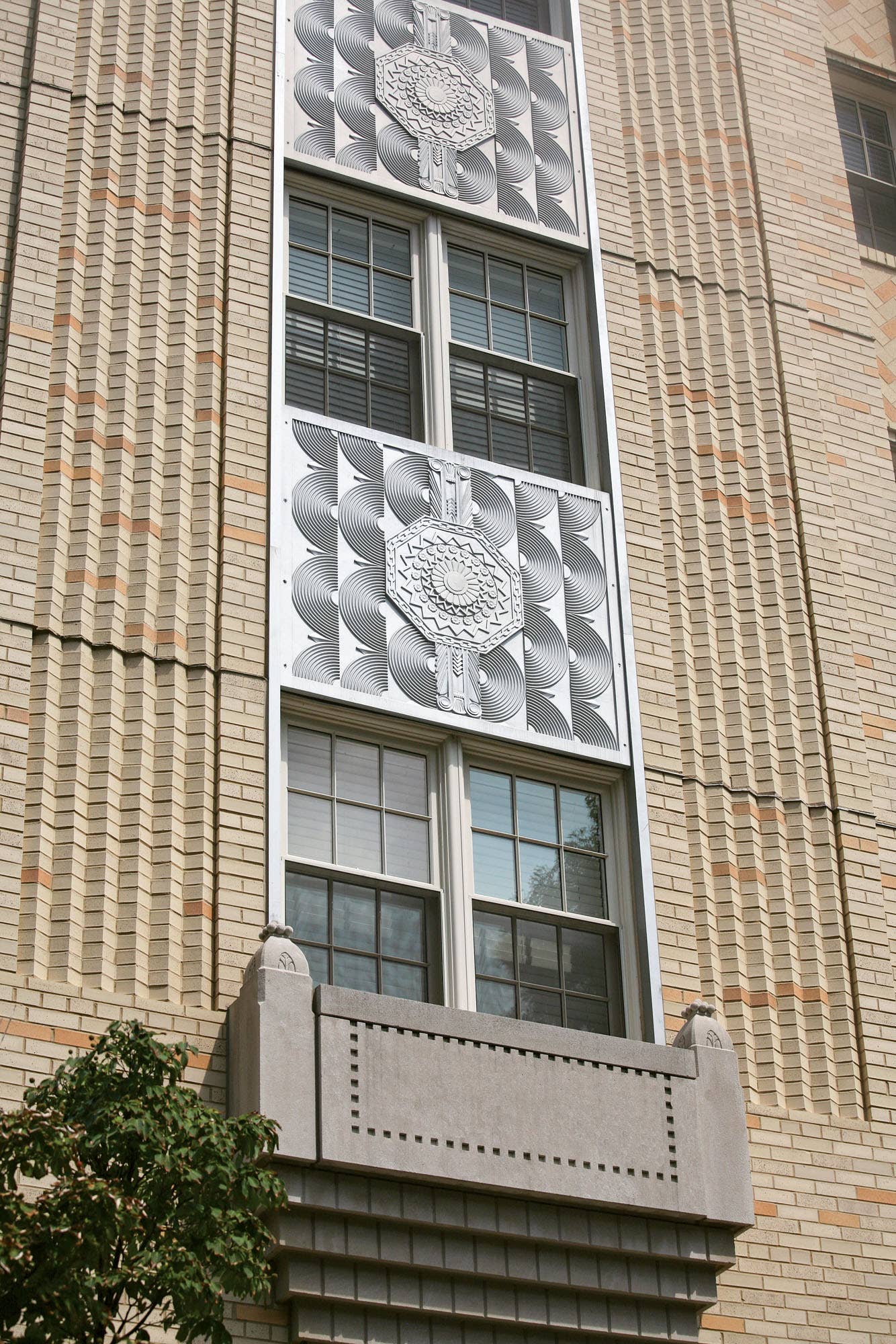

Two Park Ave., New York City

Gladding, McBean created some 650 terra-cotta pieces for Manhattan’s Two Park Avenue, a New York City landmark designed by architect Ely Jacques and completed in 1927. The Art Deco/Modernist style commercial structure, which has 29 above-ground floors, features a series of setbacks decorated with geometrical terra-cotta ornamentation.

After gathering fragments of the highly ornamental units and using various site survey methods for the other units, Gladding, McBean made replacement pieces, which range from 12 to 18 in. tall by 8 in. wide to 2 ft. tall and 2 ft. wide. The jewel-tone pieces—black, magenta, bright green, tan, two yellows and azure—have multiple glazes.

“Recreating the glazes was exciting for our glaze ceramicists,” Jess Ouwerkerk, project manager/surveyor in the Northeast says. “We typically only have to develop one or two colors for a building. This building is distinctive because it is not only the terra cotta’s form but also the varying glaze colors that work to create patterns on the façade. Matching existing glazes can be complex since they have to be formulated with materials available to us now, and these can be different from historic materials.”

Although the original terra-cotta pieces were handmade, Gladding, McBean used an extrusion process that Ouwerkerk compared to pasta making to create the units that had simpler geometric forms. “Material is extruded through a die and then cut into units,” Ouwerkerk says. “As a result, it is a faster process than hand-pressing. The extruded units are true to the form of the original pieces; however, their production has been modernized and streamlined. Extrusion doesn’t alter how the units appear on the façade of the building although they might attach into the building a bit differently.”

Bricks and Pavers

The Belden Brick Co.

Canton, OH

The family-owned company traces its roots to the Diebold Fire Brick Co., which was founded in 1885 by Henry S. Belden. The Beldens—Robert F. and son Robert T. along with cousins Brian and Bradley—are the principals in what has become the nation’s sixth largest brick manufacturer in America.

The company, which has an annual production capacity of 250 million bricks, operates five manufacturing plants and one saw house in Sugarcreek, OH. It specializes in manufacturing custom extruded and molded bricks that match traditional colors and sizes.

Brian Belden, vice president of sales and marketing, says that the company is able to produce replicas of historic bricks because it has five plants that span nearly a century. Plant No. 4, built in the 1920s, features traditional beehive kilns; Plant No. 6 was built in the 1950s; No. 8 was added in 1968; No. 3, which produces molded brick, was acquired in the 1970s and rebuilt in the 1980s; and the newest, No. 2, was built in 2000.

Belden Brick uses photos or samples to create the replicas. “Sometimes, we have the appropriate bricks in our inventory,” Belden says. “If we don’t have it, we create it. Usually, it’s just a matter of tweaking the materials, changing the fire temperature or including additives like manganese to get the right color.”

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Darwin D. Martin House Complex in Buffalo, New York

Belden Brick made custom bricks for the Darwin D. Martin House Complex in Buffalo, NY, which was constructed between 1903 and 1905. The complex—the Martin House, the Barton House, a carriage house, conservatory and pergola—is considered one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s greatest Prairie School projects.

The restoration, which took some 40,000 bricks, included reconstructing the demolished outbuildings. The iron-spots brick, which Belden made in the 1920s beehive kilns in its No. 4 plant, was a unique size—12 in. long, 4 in. deep and 1⁄ in. tall. (A typical Roman brick is 11⁄ by 3⁄ by 1⁄.) “We got the color by changing some of our firing temperatures and flashing in the kiln,” Belden says. “It was the most difficult part of the project.”

Kennedy-Warren Building, Washington, DC

When a wing was added to the historic Kennedy-Warren apartment house in Washington, DC, Belden Brick provided matching brick, including some in special shapes. The Art Deco building, a District of Columbia Historic Landmark that is on the National Register of Historic Places, was designed by Joseph Younger. It opened in 1931 with 210 apartments. A wing, part of the original plans, was added in 1935, but the Great Depression delayed the other wing, on the south side, until 2004.

The 21st-century wing followed Younger’s exterior design and included some 200,000 bricks. “There were multiple colors of brick used that ranged from creamy grays to iron-spot buff,” Belden says. “These were stock items, and we blended them together from two of our plants. The grays came from No. 8, and the buff from the 1920s plant, No. 4.”

Gavin Historical Bricks

Iowa City, IA

The largest supplier of reclaimed antique paving and building material in America, Gavin Historical Bricks has shipped product to every state in the country. The company was founded 20 years ago by John Gavin. His son, Mike, joined him 15 years ago. “It started as a hobby,” Mike says. “My dad got interested in the old pavers that were being removed from the streets in Williamsburg, IA. He bought some and did his driveway. He had a lot left over.”

Initially, the company concentrated on paving stones, which still forms the bulk of its business. It also buys antique brick from demolition companies. “We want ultra-high quality,” Mike says. “We’re choosy about which projects we buy from. Antique brick and pavers are not in endless supply. They are a luxury item that gives an authentic, unique look.”

Although the company recently bought a large quantity of granite cobblestones from a St. Louis street, Mike says that they are “tougher and tougher to come by” because towns are preserving what they have.

The company, which includes a crew of eight, works on residential as well as commercial projects. “Our bricks and pavers are in the homes of variety of people—Hollywood celebrities, Nashville musicians and CEOs,” he says. “And our commercial side has really grown.”

At Mateo, Los Angeles

Gavin Historical Bricks supplied four kinds of antique brick for At Mateo, a new-construction dining and shopping development in Los Angeles’ Arts District. “This was one of our biggest projects,” Mike says. “We supplied hundreds of thousands of bricks that were saw-cut to ⁄ of an inch.”

The antique brick, which was used on the exteriors and on some interiors, brings the development in sync with the surrounding warehouse spaces that date from the early 20th century. “The architect and designer wanted to make it look like it happened organically,” he says.

Firehouse Hook and Ladder No. 8, New York City

Built in 1903, the Beaux-Arts firehouse, which starred in both Ghostbusters movies, is undergoing a $6-million renovation that includes restoration of parts of its brick façade.

Gavin Historical Bricks supplied about 1,000 antique bricks for the project. “They sent us photos and we matched the age and look of the existing brick,” Mike says. “We did it all while sitting in our offices in Iowa City.”

Mike says that Gavin Historical Bricks is excited about the future. “We’re really passionate about reclaiming antique brick and stone,” he says. “We think demand will continue to grow.”

Mold-Making and Casting Compounds

ABATRON INC.

Kenosha, WI

The family-owned company, which was founded in 1959, manufactures flexible mold-making and casting compounds. It also creates molds and castings. Most of its castings are made with epoxy, plaster and concrete. During the 1980s, the company expanded and began to fill the demand for high-quality building restoration products. ABATRON provides products that are easy and safe to use and that are environmentally safe, permanent and at the top of their product category in performance.

Lion’s Head Mold and Casting

The lion’s head that ABATRON uses in its publicity photos and offers in its catalog was bought at a silent auction in St. Louis. It originally decorated the façade of a hotel and was saved from the wrecker’s ball when the building was razed.

“A customer recently wanted castings for her shop,” says President Marsha Caporaso, whose husband founded ABATRON. “We found an original mold that we made years ago and made the castings. The customer was thrilled.”

The casting was made with ABATRON’s WoodCast, a lightweight epoxy casting compound, and WoodEpox, a lightweight epoxy wood filler. The mold was made with MasterMold 12-3, a flexible polyurethane paste that was developed to make molds of architectural elements that cannot be removed from the site.

“The challenge in making the mold was that it has to be flexible enough to be pulled from deep undercuts and strong enough not to tear,” Caporaso says. The one-part mold is reusable. The model was coated with a release agent to prevent MasterMold from sticking to it. A thin layer of MasterMold was brushed on the model followed by a thicker layer (1⁄4- to 3⁄8-in.) applied with a putty knife.

Finials

ABATRON made three finials, each 25x13 in., from a hollow-metal model. The mold was made with MasterMold 12-8, a pourable version of MasterMold 12-3. A form to contain the liquid material was fashioned. “The biggest challenge was the widely varying dimensions of the model,” Caporaso says.

The castings, which were made with WoodCast and WoodEpox, a lightweight putty that can be applied in relatively thin layers to create hollow castings, were made in stages. The ball tops of the finials were reinforced with wooden dowels.