Product Reports

Restoring Eldridge Street Synagogue’s Art Glass

By Arthur J. Femenella

The synagogue of Khal Adath Jeshrun in conjunction with Anshe Lubz, better known as New York City’s Eldridge Street Synagogue, is the first, and considered by many architectural historians the finest, synagogue erected on the Lower East Side of Manhattan by the East European Ashkenazi Jews.

Designed by German immigrants Peter and Francis Herter, the synagogue was built in 1887. For its first 40 years, it was supported by a growing community of “lawyers, merchants, artisans, clerks, peddlers and laborers,” according to an 1892 article in Century Magazine. In the 1920s, the stream of immigrants began to wane, and by the 1950s, a small but loyal congregation remained and celebrated services in the lower chapel.

This continued into the 1980s, but the lack of local support resulted in the deterioration of the building fabric. The sanctuary was sealed from the balance of the building. There were holes in the roof, pigeons roosted with impunity and the glorious leaded-glass windows were covered with the dust and the grime of the city.

Well-known New York preservationist and writer Roberta Gratz joined forces with attorney William Josephson and formed the not-for-profit, non-sectarian Eldridge Street Project in 1986. This was my first connection with the synagogue. While an owner at the Greenland Studio, I visited the synagogue. We were part of a team formed to assess the level of damage and to later create a mockup of one of the restored leaded-glass windows. Gratz and Josephson persevered and managed to mount the largest independent restoration effort not supported or attached to an institution or government agency in New York City.

Ultimately, the funds raised enabled the full restoration of the synagogue to its former glory by Walter Sedovic Architects, based in Irvington-On-Hudson, NY. (See TraditionalBuilding, December 2006). In addition, the funds raised were used to form the Museum at Eldridge Street to present the culture, history and traditions of the great wave of Jewish immigrants to the Lower East Side.

As part of the restoration, the Gil Studio of Brooklyn, NY, and Femenella & Associates of Branchburg, NJ, collaborated to restore the historic leaded-glass panels and wood window frames.

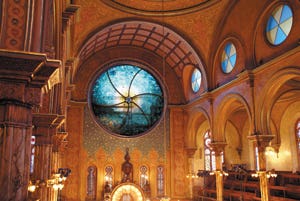

The New East Window

That the sanctuary had gone for so long without maintenance clearly had resulted in serious deterioration of the building fabric and finishes. However, this same lack of maintenance, or more correctly lack of renovations, had left very direct evidence of the original finishes and decoration so they could be faithfully restored or replicated.

This was not the case for the large east window that was over the ark. In 1944, this window was lost from the building. The most plausible cause was storm damage. At the time, the congregation could not afford to restore it so they replaced it with four lancets of glass block with Roman arched tops. The balance was in-filled with brick and plaster.

There was no record of what the original window looked like, so the question was, what should be done? Copy one of the existing windows? Design a window of the period employing existing design schemes within the building? Preserve the glass block lancets? The museum realized it needed help with this most important decision; they met with preservationists, leading architects, historians and museum curators to determine the most appropriate course of action. In the end, the museum decided to commission a new window for the space. A number of artists submitted designs for consideration by the museum. Ultimately, the design team of artist Kiki Smith and architect Deborah Gans was selected to design the new window.

There was no record of what the original window looked like, so the question was, what should be done? Copy one of the existing windows? Design a window of the period employing existing design schemes within the building? Preserve the glass block lancets?

In 2007, the Gil Studio was awarded the contract to restore the Eldridge Street Synagogue's art glass. Tom Garcia, president of the Gil Studio, selected Femenella & Associates to design and fabricate the custom frame and to handle all site work and the installation of the frame, new glass and protective glazing system.

Tim Allanbrook, senior consultant from Wiss, Janey, Elster Associates in New York, oversaw the frame and installation details, and Terry Higgins, president of T. Higgins Construction, was the general contractor for the project, providing scaffolding, logistical support and related trades. Executive director of the museum Bonnie Dimun and deputy director Amy Stein Milford were both closely involved in the project. It was a true collaboration of art and design professionals, craft and superior administrative abilities that pulled this project together.

The Kiki/Deborah design is truly inspirational but instantly created perspiration for those of us who had to execute the work. Gans's frame design idea was distilled from sacred geometry and called for a 16-ft.-dia. window with a very small Magen David center, the balance divided into six segments. Each segment was approximately 30 sq. ft. and did not lend itself to the reasonable constraints of a traditional leaded-glass window.

The design team decided to use mouth-blown Lamberts Glass (supplied by Bendheim of Passaic, NJ) and a laminated process developed in Germany. The process uses an optically clear silicone to adhere the art glass to the substrate, thus obviating the problems encountered with many previous lamination projects wherein less flexible adhesives were employed.

The process involves two layers of Lamberts’ full antique flashed glass to be etched, silver stained, gold leafed and then applied to a 3/8-in.-thick laminated base layer of clear float glass. Once the path was determined, a digital photo of the artist’s full-size cartoon was imported to a CAD program, which allowed Garcia to position each of the four different-sized stars in the correct location and orientation and to mark each one as silver stained on one layer, both layers or indicated as gold leafed. The design was the printed full size for each layer.

The artist’s cartoon did not indicate cut lines, so these had to be determined before the project could move forward. The cut lines were initially indicated by Audrey Morrell of the Gil Studio and were then revised and finalized by Gans. Patterns were cut using pattern shears just as would be used for a leaded window. This resulted in lines of light between the glass pieces that are visible and add sparkle to the finished window. The cut lines for the two layers are radically different, but the stars had to be in correct registration because they were etched on both layers of the flashed glass. The glass is Lamberts’ 2352 blue on clear that is formulated with copper, making it slightly greener than the other cobalt blues of the Lamberts line. The glass selection was initially determined by Gans and Smith. The shading of the glass pieces within the window (darker at the outside and gradually lightening towards the center) was determined by the artists through mockups and studio visits during the cutting process.

Cutting the Glass

Morrell cut much of the glass (she also did a lot of the etching), and the glass was then prepped for etching, employing contact paper on both sides of virtually all the glass, approximately 1,200 separate pieces. The pieces were first hard etched to inscribe the stars; the blue pieces were then brush etched as they approached the center of the window, gradually becoming totally clear. Silver stain was applied to the lower or inner layer of antique glass to modulate the blue color. The etched stars were silver stained on one or both layers as indicated by the full-size cartoon. For the stars that are not etched, 23-karat gold leaf was applied with an oil sizing. This created reflective stars as a counterpoint to the transparent silver-stained ones.

Then the true fun commenced. The laminated glass was meticulously cleaned and placed onto the table on top of the respective section of the cut-line drawing. A dam was placed around the edge of the laminated panel. Each of the blue pieces to be laminated was then prepped by thorough washing and an application of a primer. The two-part silicone that would adhere the glass to the substrate was then prepared. The silicone is an optically clear, flow-able material manufactured in Germany. It was originally developed to encapsulate electronic parts, primarily for the solar cell industry.

Once mixed, the silicone has the consistency of honey and remains workable for approximately 1 1/2 to 2 hours. It vulcanizes in 24 hours. The silicone mixture was poured onto the laminated glass and the antique glass was then quickly but expertly set into the proper positions. Another application of silicone was completed, and the second layer of antique glass was then prepped and applied.

Frame Design and Fabrication

Meanwhile, Femenella & Associates, led by Patrick Baldoni in concert with Richard Goloveyko, was working out the design of the frame and the installation details. The final frame would be 16 ft. in dia. and 6 ins. deep and would be made from solid bar steel stock with architectural bronze angles retaining the laminated panels. Based on our prior experience with laminated glass, Baldoni determined that it would be a good detail to wrap the laminated panels in lead, thus preventing accidental contact with the steel frame. For this purpose, a custom extrusion was provided by DHD Metals of Conyers, GA. The lead was applied by Gil prior to the pickup of the panels; it was adhered to the glass with a neutral cure silicone.

The frame design and fabrication presented a number of challenges. The central Magen David, the articulated ribs and the minimal sight line desired by Gans dictated that the tolerances for the laminated glass panels would be very tight. To further complicate matters, Allanbrook was concerned about the loading of the frame because we could not successfully computer model how the frame would react to high winds. And don’t forget that it might be a problem transporting a 16-ft.-dia. steel frame that weighs in excess of 5,000 lbs. from Pennsylvania to Chinatown on a flatbed truck and setting it into the rear of a building that is completely surrounded by old tenement buildings and warehouses.

After many hours of meetings and conference calls, Baldoni worked out the solution. To facilitate travel, the frame was made in three equal sections. It was bolted together at the shop, carefully marked and then taken apart. To address the loading issue, prior to breaking down the frame, it was set horizontal in the shop and weights were added to the center of effort of the frame to simulate the loading of hurricane-force winds. The design exceeded expectations. The control was for maximum deflection of ½ in.; the frame deflected less than 3/8-in. – a resounding success.

At the site, custom plates were installed on the masonry that would be field welded to the steel frame once it was set into position. Test loads were also applied to these setting plates, and they held. To facilitate the construction schedule, once the design of the frame was completed, CAD drawings were sent to Gil so that they could start the layout process and begin cutting glass. This data was also sent to J. Sussman & Co.; it would produce bent aluminum extrusions that would be bolted onto the steel frame to carry the exterior glazing for the window.

We were confident that the layout provided was accurate to plus or minus 1/8 in. We also used the CAD data to cut Masonite templates for the laminated glass. Fabrication of the decorative glass and the frame proceeded concurrently. Once the frame was complete, the Masonite templates were fitted and verified. The laminated glass was then water-jet cut and sent to Gil for lamination.

The installation deadline was quickly approaching. Mayor Bloomberg and various other luminaries were invited for the unveiling; we could not afford to drop the ball. Access to the site was severely restricted. We had to use the parking lot of a warehouse behind the synagogue to set a 100-ft. crane, and we could work only on Sundays; we had to assemble, hoist and install the frame in one day.

The frame sections were delivered to the site, and the crane was set. Once assembled and welded, the frame was ready for lifting. It was like a scene from a Fellini film. Due to the tight location and the way that the scaffold had to be set, we had to hoist the frame over 80 ft. in the air and drop it between the synagogue wall and the scaffold; a 5,000-lb., 6-in.frame had to fit into an 8-in. space and then be manipulated about 18 ins. into the window reveal. All the while, we were watched by 30 elderly Chinese men playing Mahjong on tables around the parking lot. Long story short, it fit like a glove. The following week we attached the aluminum frame to receive the vented exterior glazing employing a polyurethane thermal break.

The laminated glass was ready to install. Each segment weighed 300 lbs. and was shaped like a slice of pie designed by Picasso with wavy edges. We cut a slot in the interior scaffold floor and hauled the glass to the level of the window, about 30 ft. off the floor of the synagogue. A suction cup apparatus was attached to the exterior of the panels, which were gently lifted and manipulated into position. Anyone who has ever set glass can appreciate the delicate ballet required to maneuver the 300-lb. sections into position.

Once placed, the panels were retained with bronze moldings. The protective glazing was to be 3/8-in. laminated glass. The interstitial space between the laminated glass and the protective glazing is vented to the exterior and weep holes are provided. After installation, Garcia, at the direction of Smith and Gans, applied an additional 40 gold-leafed stars to the composition.

This was an amazing project for all those involved. The design, fabrication and installation of the new window took a total of 10 months. The installation began in December of 2010 and was completed a month later.

The unveiling ceremony went off without a hitch, with many kind words from Mayor Bloomberg and other notaries. Robert Tierney, chairman of the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission, stated, “With the installation of Kiki Smith and Deborah Gans’s extraordinary window in this sacred landmark, Eldridge Street’s evolution now spans three generations – built in the 19th century, preserved in the 20th and renewed in the 21st.”

Funding for the Kiki Smith-Deborah Gans window was provided in part by American Express, the David Berg Foundation, the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation, the David Geffen Foundation, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and the New York State Council on the Arts. A special thanks to Tom Garcia of the Gil Studio in Brooklyn, NY, for his assistance in preparing this article. Come, see, enjoy. TB