Projects

Robert A.M. Stern Designs New Colleges at Yale

Project: Benjamin Franklin College and Pauli Murray College, Yale University

Architect: Robert A.M. Stern Architects, New York, NY; Robert A.M. Stern, Senior Partner; Graham S. Wyatt, FAIA, Project Partner; Melissa DelVecchio, AIA, Project Partner; Jennifer Stone, AIA, Project Partner

At a time when some textbook examples of the historical revival quad—think Duke University’s “Gothic wonderland”—are building anew outside of their architectural boxes, Yale University is completing a major expansion that is as of a piece with its existing campus as it is ground-breaking.

Two new residential colleges, Benjamin Franklin and Pauli Murray, the work of Robert A.M. Stern Architects of New York, will house some 904 new resident students—supporting a 15% increase in Yale’s undergraduate enrollment—as the 13th and 14th colleges in Yale’s residential college system, carrying forward the Gothic template of the University, and the ideas of architect James Gamble Rogers, in a seamless 21st-century set of buildings.

The residential college system at Yale has its origins in the early 20th century with one of its most influential alums, the architect James Gamble Rogers. The 1917 Memorial Quadrangle designed by Rogers was the first use at Yale of an enclosed quadrangle for student living, but being basically a dormitory, it did not include other components of a true residential college such as a dining hall, a library, or a common room. In the 1930s, Yale decided to convert to a true residential college system, closer to the Oxford/Cambridge model. Between 1929 and 1936 Yale built eight more colleges in the Gothic and Georgian styles, six designed by Rogers and two others designed by John Russell Pope and Pope’s successor firm, Eggers and Higgins.

Today’s new colleges are a milestone development—the first significant additions in 50 years—and yet not so radical. The last two new colleges to open, in 1962, were by architect Eero Saarinen in a Modernist interpretation of the Gothic. However, when planning for Franklin and Murray colleges began in 2008, there was little discussion about whether they should be modern or traditional. “Yale very much wanted these buildings to be traditional,” explains Melissa DelVecchio, AIA, a Partner at Robert A.M. Stern Architects. “That’s why they hired us.” Robert A.M. Stern, a former Dean of the Yale School of Architecture, is well-known as a proponent of respect for context and the continuity of tradition.

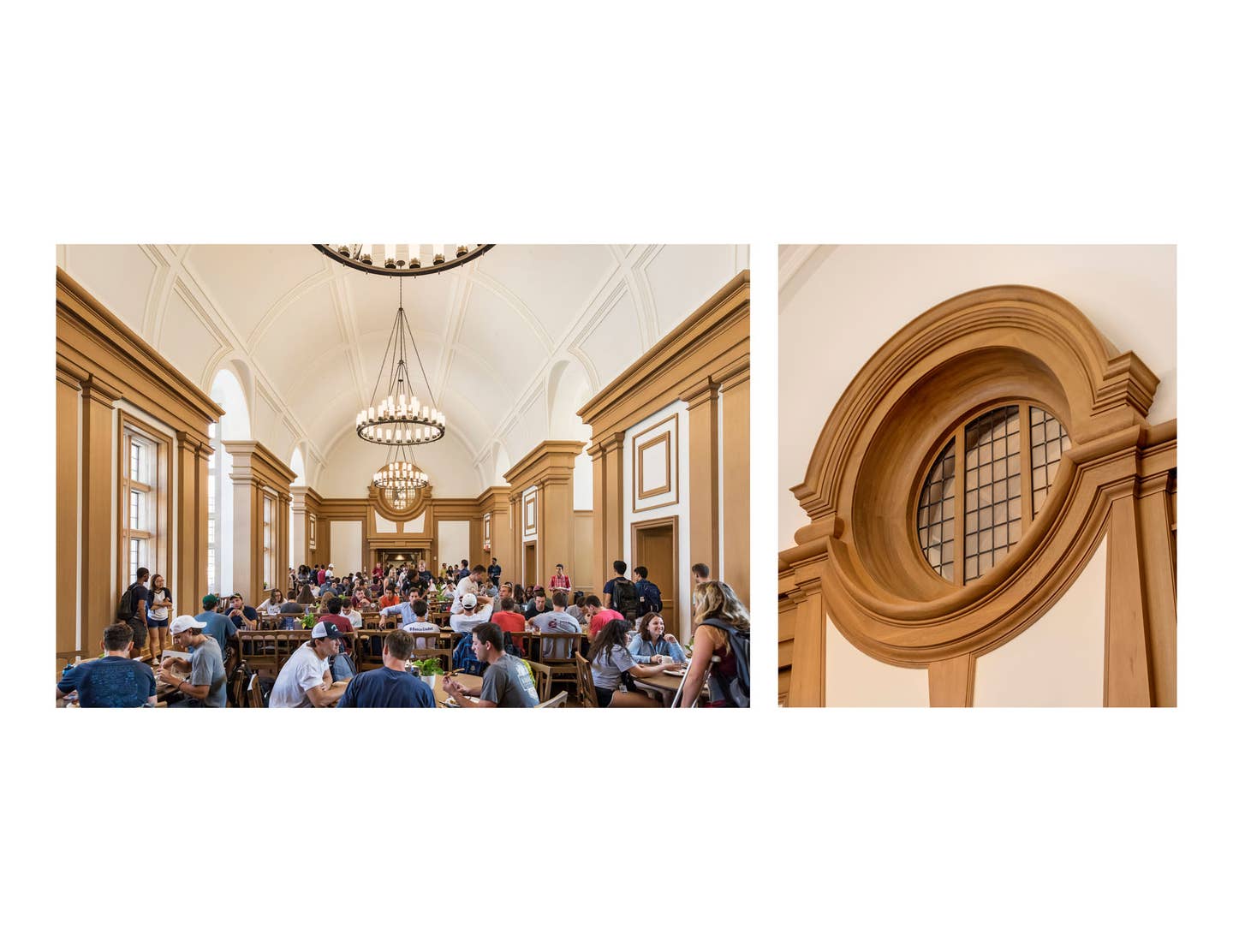

As DelVecchio explains, “Both of the new colleges follow an established pattern for residential life that already exists on the Yale campus and is at the heart of the Yale College experience.” Physically, each college comprises a series of courtyards around which are built student rooms, a house for the head of each college, apartments for the deans, and the college’s own dining hall, library, and common room. “The colleges are not dormitories; they’re communities,” she emphasizes, “and this is a program type that’s been part of Yale’s DNA since the 1930s.”

Tradition and continuity have their symbolic worth, but they can also be turned to practical purposes. “At Yale, many of the existing colleges are Gothic,” says DelVecchio, “but a few of them are in the Georgian style, recalling Yale’s early history. Bob Stern argued that because most people consider the identity of Yale to be Gothic, and since most of the nearby former Sheffield Scientific School—now Yale’s Science Hill—shares Yale’s Gothic expression, these new colleges would create a better connective context between the central campus and the buildings on Science Hill if they were Gothic.”

In the end, she says the flexibility of the Gothic architectural language—allowing for asymmetry as well as symmetry—helped the architects solve complex planning issues across the 6.7-acre triangular sloping site. “The idiosyncrasies you see in the facades are true expressions of the program behind.”

“The scale and complexity of the project are really significant,” says Graham S. Wyatt, FAIA, a Partner at Robert A.M. Stern Architects. “It has a mile and a half of non-repetitive Gothic facade, all of which needed to meet the exceptionally high standard of quality that characterizes the Yale campus.”

He points out that extensive research by the design team was essential to achieving that standard. “Our team pursued research of several types. We looked carefully at the original Yale residential colleges, not just wandering around, but considering them carefully, measuring them, and photographing them. At the beginning of the design/development phase, we divided our sizable team into sub-teams that were assigned specific topics. Team members studied dormers, chimneys, or windows, for example, observing these across campus and documenting them carefully.”

He adds, “Others studied light fixtures, wrought iron, and stonework and the detailing of its integration into brickwork. People became subject-matter experts in these areas and brought that expertise back to the team, so the team as a whole benefitted not only from our early document research but also from this focused, on-the-ground research”

One of the functions of the new colleges is to better connect the site visually with the rest of Yale. The campus is very long and thin, explains DelVecchio, two miles in distance north to south, at its mid-point almost cut in half by the walled Grove Street Cemetery, making the walk from the central campus to the site along Prospect Street, seem long and isolating. “Students told Bob Stern that the walk up Prospect Street from the central campus to the site of the new colleges felt like the Ho Chi Minh trail,” she says. “One of the main goals of our design was to collapse the perceived distance between these buildings and the main campus.”

One of the many ways the architects achieved this was with the carefully studied placement of towers. They used a very large site model that included all of the main campus, including the James Gamble Rogers colleges, to study the alignment of the towers with the axes of important streets of the main campus. “The new towers act as important visual markers and enter into a conversation with the other elements of the Yale skyline,” says DelVecchio.

Enclosed quadrangles are also part of the template for the residential college system. “There’s typically one large courtyard where the colleges celebrate commencement, sized to accommodate tents for students and their parents, DelVecchio explains.” Students have their commencement ceremony on the old campus, but then they go back to each of their colleges to receive their diplomas. “Yale has a tradition of large, medium and small courtyards, but there’s also a tradition of very small courtyards,” notes DelVecchio. “We did a lot of studies of their size and scale on the main campus so that the new colleges’ courtyards would feel like they belong.”

Choosing characteristic Yale materials for the new colleges was much more than a matter of perception. “People generally think of Yale as being an entirely grey stone campus, but in truth, it’s largely brick,” says DelVecchio. Both the Georgian buildings, and several of the important Gothic buildings, like the Hall of Graduate Studies and the Law School, as well as many of the Gothic courtyards, are brick or a combination of brick and stone.

“James Gamble Rogers used stone selectively to emphasize important spaces on the central campus, often shifting from stone to brick within a single building or along a given street. Rogers’s buildings go from mostly stone to mostly brick with more limited areas of stone detailing the farther they are from the center of campus,.” The design team’s focus was to follow the pattern of material use established by Rogers and to use a palette that would help to knit together the brick buildings at the perimeter of the central campus with the many brick buildings on Science Hill.

Like the Rogers facades at Jonathan Edwards College, the Hall of Graduate Studies and the Law School, the brick facades are embellished with Weymouth granite from Massachusetts, Indiana limestone and cast stone. “James Gamble Rogers also used cast stone,” she says. “Limestone appears mostly at the ground floor for archways and other unique elements, while we took advantage of cast stone for more repetitive elements, like the student room window surrounds.”

Prefabrication offered other efficiencies. For example, brick-and-stone vaulted ceilings were cast at a factory in Canada, then shipped to the site and lifted into place in outdoor passageways. Chimneys—some active fireplace flues, but most concealing air intakes, exhausts and plumbing vents—were also fabricated off-site, as were the upper portions of the new 192-ft. Bass Tower. These strategies were important for controlling the budget for the 1.5 miles of facade.

DelVecchio points to the extensive program of carved stone ornament in keeping with the Rogers colleges, 400 pieces in all. While the many Gothic architectural details, such as buttresses, archways, and finials were designed by the architects, campus historian and artist Patrick Pinnell (Yale BA 1971, MA Arch 1974) was hired by Yale to design commemorative decorative panels that speak to the history of Yale and New Haven.

Masonry facades with a high wall-to-window ratio materials contribute to more than just traditional appearances; they will also help the project earn a LEED Gold rating. The windows of the new colleges look like traditional Yale casements from the outside but are, in fact, very modern and energy efficient. They include a true leaded restoration glass panel on the outside, but behind that is a full insulated glass unit. Geothermal wells in the courtyards provide 10% of the energy savings needed to achieve LEED goals.

Heating and cooling for the student rooms are delivered through a passive valance system that requires neither fans nor ductwork. This heating and cooling strategy also has another advantage: because no ductwork was required, the team was able to design the buildings with floor-to-floor heights similar to those in James Gamble Rogers’ buildings, allowing the architects to keep the proportions of their buildings similar to the Rogers precedents.

When James Gamble Rogers initially presented his designs for the Memorial Quadrangle to Yale, he presented two elements—a partial floor plan showing the residential module that repeated around the site, and a plaster massing model. Stern’s team calls this “working from the inside out and from the outside in,” DelVecchio tells us, and her team used the same process in designing the new colleges.

It’s no mystery that James Gamble Rogers studied the buildings at Oxford and Cambridge Universities, but he took a much different approach than just “channeling” these medieval models for Yale. As DelVecchio explains, the Oxford and Cambridge colleges typically have one or two courtyards enclosed by buildings of a fairly uniform height. “Here in New Haven, Rogers’ massing strategy was more complex. Rogers placed taller buildings on the north side of a courtyard and lower buildings on the south side to maximize sunlight in the courtyards.” Stern’s team followed this same concept.

Yale also challenged the design team to find a way to retain the essential spirit of the Yale entryway system. Traditionally suites at Yale were organized in vertical entryways comprised of suites containing a common room and bedrooms organized around a shared stairwell and bathroom, but this arrangement does not meet current egress and accessibility codes. Stern’s team developed what they call a “modified entryway” where two stairwells are connected by a short corridor with an elevator and shared bathrooms. This modest expansion of the traditional Yale model meets current codes, and also allowed the team to keep the width of the floor plate narrow —35 ft. 6 in.—very close to the 33-ft. width of the Rogers module and much narrower than a fully double-loaded corridor. “If we were to design big suites on both sides of a double-loaded corridor, the floor plate would have to be much wider and the roof would have been much bigger, and all of a sudden the building would look out of scale with everything else on the campus.”

Continuity, once again, was the goal. “Yale wanted to retain the vertical entryway social structure, and we wanted to capture the same special sense of scale that the James Gamble Rogers buildings have,” says DelVecchio. “The idea of making the new Yale residential colleges traditional, in both form and expression, is to ensure that students have the same Yale experience, whether they’re living in the new colleges or the older ones.”

Key Suppliers

Construction Manager: Dimeo Construction, Providence, RI

Landscape Architect: Olin Partnership, Philadelphia, PA

Ornamental Cut Limestone: Traditional Cut Stone, Mississauga, ON, Canada

Architectural Ornament: Patrick Pinnell, Hartford, CT

Cast Stone and Precast Concrete: BPDL, Alma, Canada

Exterior Wall Systems: Glen-Gary Brick, Wyomissing, PA

Leaded Glass Windows: Rohlf's Stained & Leaded Glass, Mt. Vernon, NY

Lighting, Pauli Murray College Library: Remains Lighting, New York, NY

Lighting, Benjamin Franklin College: Crenshaw Lighting, Floyd, VA

Furniture, Pauli Murray College Dining Hall: Thos. Moser, Auburn, ME

Indiana Limestone: Reed Quarries, Inc., Bloomington, IN; Indiana Limestone Fabricators, Spencer, IN; Indiana Limestone Company; Bloomington, IN; Bybee Stone Co., Ellettsville, IN

Metalwork: Wiemann Metalcraft, Tulsa, OK

Exterior Gates: Covax Design & Atelier, Clifton, NJ

Millwork: Millwork One, Cranston, RI

Roofing: Carlisle Syntec Systems, TPO Vermont Slate, Carlisle Slate, Carlisle, PA

Windows: Crittall Windows Ltd., Witham, UK

Custom Hinged Screens: Allied Window, Inc., Cincinnati, OH

Gordon Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute (www.npi.org), and a speaker. He can be reached at www.gordonbock.com.

Gordon H. Bock is an architectural historian, instructor with the National Preservation Institute, and speaker through www.gordonbock.com.