Ken Follett

William Blake Cut Sharp Marriage Marks

I like how Rudy refers to the circuitous route by which trades tend to get to where they are though I would want, for cultural reasons, to flip this perception on its head. I have usually known pretty well where I wanted to go, if only I could find a way to get there. If there was a circuitous part, then it came about mostly from my listening to other people, teachers, adults, guidance counselors, misguided mentors, friends, telling me that I could not get to where I wanted to go.

I know a good number of folk in the traditional trades who knew full well right along that was where they wanted to be. Often enough there was pressure from their families to be something else, and they had to learn to resist. I consider this the “cantankerous” generation that came along with an attitude of, “No way, not us, we won’t go.”

This irritable, though valiant, resistance, by the way, has a tendency to become ingrained in habits of thought and feeling and quite often will bleed over into project teams. Such as the oft-encountered sense of adversity, a false one that I do not have space enough to go into presently, between the person who designs with lines and the person who uses a hammer and a chisel to cut lines.

But I step back from a reactionary impulse and begin to think about where a belief originates that one can live a good life thoughtfully while working physically. I believe it has to do a great deal with our ability to see options, to see opportunities, to visualize a path, to know where the next step is. Just as with a revolutionary, a rioter, a victim or suicide, the options, opportunities, and the vision of a path forward may not be there.

At one time in my youth my life was a bit messed up and it occurred to me that, as with many at a point in their lives, I had no clue what I wanted to do with myself. I decided that doing anything would be better than wondering what not to do next. I’d pretty much given up on going to college (I kept applying to a working cattle ranch and school near Death Valley), and so I said to self, “I think I will go to Japan.”

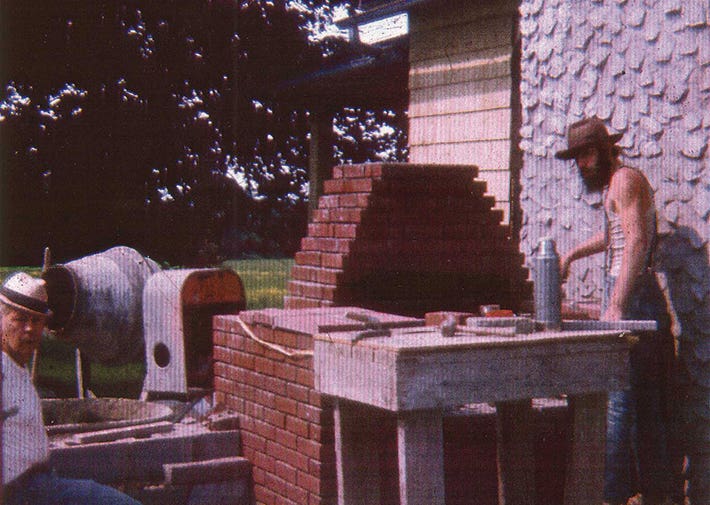

So, I drove alone to Oregon from upstate NY, and after a half year, including several months working as a cook in a restaurant on a Native American reservation, I hitchhiked back. I never left the American continent. I never got on a boat. At some point not long after my return to the family home I was piling up stones in a creek – not as sophisticated as that YouTube guy that balances stones – and it was then I decided that I wanted to learn to build fireplaces. Not long after that I was delivering bull manure – it was my first honest business – and I met a stonemason who was as old as I am now. He needed a mule and I went to work. He sort of taught me how to build fireplaces, and he also taught me how not to build them. The idea that one should only learn from people who know what they are doing is misleading. I now know that in winter the white stuff on the frozen trowel was ice and not a sign of the mortar setting up quickly. I worked with him for three years. Twelve-hour days, six days a week. I think of him often these days as I look around at the world of trades work.

A point of my early bias in respect to formal education can be illustrated with an exposure that we had for a few days of patio and barbecue building when a young fellow about my age came along. He was recommended by someone’s aunt or uncle. He told us he wanted to be a stonemason and that he had gone to school in Denmark for it. This poor kid was a dunce when it came to stonework. We had to shuffle him off fairly quickly. He may have had a paper certificate in stonework. (I have nothing against Denmark.)

What I came to learn was that if I wanted to learn how to do a thing, then it was up to me to go find someone who knew how to do it and to then do my best to work hard and gain their approval so that they would feel inclined to teach me. My career has been a movement from my choice of one mentor to another until one day I looked around and wondered where they had all gone off to.

Some may say that my learning was imbalanced.

I have a habit of finding people that I think are angels. This one day I had off from work, it had to be a Sunday, and I was sitting on the wall at the local bank and this guy came along and asked me for $5. He said he did not want just $5 for nothing, but that he wanted to talk with me for a while and then I could decide if I wanted to give him $5. So we talked.

He asked me what I did for a living and I told him about building fireplaces and doing stonework and out of the blue he pointed to the row houses across the way and said, “One day people will be asking you how to fix buildings like that.” It was then I thought he may be a bit nuts. But, eventually that is exactly what I came about and learned to do. See, there is a seed to every vision, and with as many visions as we can hold there are more options and more opportunities.

But, I can also revert to what Rudy says about starting out in one direction and ending up in some other place. I actually started out wanting to be a poet. I may still be one, but taking up a sledge hammer and banging on glacial cobbles to split them open and reveal the minerals, crystals and colors of their insides and then building a wall of them is a compulsion all unto itself.

At one time I wanted to be a zoologist with a specialization in animal behavior. We have had all sorts of pets over the years. Another time I wanted to be a goat herder and build a yogurt empire, but then we got pygmy hedgehogs and I felt downsized in the dairy industry. Instead, I like to make wine out of weeds and flower petals.

Though my rambling here may seem off the mark, the point I want to make is that very often when I am engaged in doing what seems the least likely to have anything to do with traditional trades, or even with historic preservation, is often where I learn the most useful skills. In some circles, it is called play. In my culture I call it meditation in motion. It is that celebration of life where our work becomes the passion, where it is not solely gauged by the pay check or the industrial hours, but by the satisfaction, the contentment of doing a thing that one is able to do and at the odd times to accomplish it fairly well.

Heros, mentors, and role models

As humans we need heroes, we need role models, we need companionship and a sense of community in shared values. Rudy asks why there is an imbalance in the implementation of the learning modes in our society. There is not much of an imbalance in my society. There may be in your society, but not in mine. Rudy often calls out that that there is a problem with our culture.

Many years ago it occurred to me that if I wanted to write just like everyone else then I should read what they read. If I wanted to write something different then, as with Thoreau, I would need to find my own dissonant drummer, and read what every other writer is not reading. Go off list, young man! The learned knowledge that comes of reading, of reading extensively, is a form of culture. There are some really incredibly dense and obtuse books out there (I confess to having read all of Finnegan’s Wake, once, while daydreaming amid mesas) and one day I had the epiphany that all those fashionable books that I don’t care to read are not in my culture. In fact, to we each have to live within our own unique culture. So, honestly, I’m not quite sure what culture it is that Rudy is calling ours. In my culture tradespeople are not only highly valued and respected, in many cases they are my friends.

One time I was in a bar and I told a stranger that I wanted to be a writer. He responded, “So stop wanting to be one, and be one.” That made sense. It shows that we can learn things at the least expected opportunity. If you want a different culture, then have a different culture. Another time, I told my painter friend that I was having a good time playing with stones and he remarked, “Well, maybe that is what you are supposed to do.”

Likewise, if one does not want to be imprisoned in a narrow minded society where the abstract function of the brain is dominant over the mind and hand at play together, then just don’t do that.

Go barefoot and run into the sun with sharp mortise chisels.

Note: William Blake was an engraver and poet. He engraved copper plates for illustrations of his poetry. That line cutting, very sharp and precise was an act of craft that in turn became a print. He had a fixation on the sharp line and rebelled against the fuzzy lines of the artists of his day. He also created a rather intense personal culture. One of his poems, written in 1790, was The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Timber framers, at least some of them, use "marriage marks" to indicate which end of a timber joins into another.

Ken Follett is a founding member and 1st past president of the Preservation Trades Network as well as a longtime member of APTI and APT Northeast. Based in Putnam County, NY, his work is primarily in the NY/CT/NJ region with occasional stints in places such as Washington, DC, and Coloma, CA. His trade background is in masonry with an emphasis on playing with stone. Beyond stone, Ken has several decades of contract experience in project estimating, administration and management. Most notably in terms of education was his two and a half years as clerk-of-the-works on a $20M redevelopment project in Harlem for the NYC Transit Authority.

Currently Ken works in partnership with his son David Follett to provide in-field support services to structural engineers, architects and conservators in their design investigations of existing and historic structures. As a hands-on project consultant, Ken assists project teams in resolution of heritage conservation problems, most recently to resolve a project-killing issue for the award winning Eberhard Pencil Factory buildings at 58 Kent Street in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Ken also gets involved in small projects, such as deconstructing and reconstructing a Stanford White fireplace, designated mason in a Guastavino tile vault workshop, righting a tipped cemetery obelisk, or matching an existing custom stucco recipe. Ken also works with heritage contractors as well as materials suppliers, assisting them in their business development.

For eighteen years Ken was executive vice-president of a specialty historic restoration contracting firm in Brooklyn, NY. In the role of contractor Ken was responsible for the negotiation, planning and project management (for which Christian & Son was a team member) to relocate Thomas Edison’s #11 laboratory building from the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, MI, to its original site in West Orange, NJ. Of similar note was assisting the design investigation team for the Edison Memorial Tower in Menlo Park, NJ (a John Early concrete panel structure). He was also involved in the preconstruction and probe investigation activities for both the New Amsterdam Theater and the Grand Central Retail Redevelopment projects in NYC. Another project of note, involving public art, was the demounting and conservation of the Paul Manship Medallions from the NY Coliseum that were relocated and mounted at the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel Ventilation Building in Manhattan at the north side of Battery Park. Ken was the contractor and project manager for the multiple award winning exterior restoration of the Barnes & Noble corporate headquarters at the north end of Union Square in Manhattan, New York.

As a writer Ken has over the years published in a number of venues including Traditional Building, Building Renovation, CRM, APT Bulletin and APT Communiqué. Otherwise Ken speaks in public rarely, prefers to encourage and enable the more bold and outspoken, and even more rarely will direct a workshop (estimating for heritage conservation work)… though he has organized quite a few workshop and work experiences for others.

Experienced in contract procedure with the following public agencies: NYC Historic House Trust, GSA, U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, US Coast Guard, National Park Service, FDA, HUD, NYCTA, MTA Bridges & Tunnels, NYC DDC, and NYC Parks.