David Brussat

Must Ugliness Trump Beauty?

I have spent the last several months tiptoeing around my hope that, whatever I may think of his broader goals, Donald Trump’s election might be good for architecture. It is not politically correct to have any positive thoughts about the new president, but perhaps Trump will conclude that to make America great again he must try to make America look great again, too.

Others seem to have been tiptoeing around similar thoughts. For example, Robert Adam pirouettes nicely around the implications of trends against globalization and for localization in architecture in his Forum essay, “Traditional Architecture and the New Politics” in the new issue of Traditional Building.

“A great deal is changing in the wider world and architecture is bound, eventually, to reflect this,” he writes. “Some of us may regret the political direction this has taken,” he adds, mentioning Brexit, the vote for Britain to leave the European Union, but hinting at Trump. “[W]e must recognize there is widespread alienation to the economic and political outcomes of twenty-five years of globalization,” he writes, explaining that major political shifts often generate a shift in architecture. Could that be happening now?

"I think that the followers of traditional architecture can take some encouragement from recent events. It is not hard to identify the architectural manifestation of global homogenization. In the 1930s Modernism was given the name “The International Style” and, while this name has been largely dropped, this is exactly what it has become. … Should we now regard traditional architecture as the movement that recognizes the disillusion with internationalism and globalization and reflects the rise of localization?

It is my belief that we should."

Modern architecture has been very unpopular with most of the public from its beginnings in Europe. It has been the establishment in America since the late 1940s, it has been displacing traditional urban habitat in the Third World for decades, and today it is the default style of the 1 percent. Trump campaigned with promises to “drain the swamp” in Washington. Modernism is architecture’s swamp.

Trump Tower suggests that the style wars may not be on his radar. Maybe Trump’s new hotel at the Old Post Office on Pennsylvania Avenue suggests otherwise. Who can say? But as a businessman and entertainer he must realize the importance of symbolism. The revolt of tradition against modernism in architecture could make his anti-establishment agenda visible in a way every American will comprehend.

In the process of tiptoeing around this whole issue, I have nevertheless suggested in a recent TB blog and on my own Architecture Here and There blog (“Vote’s style-wars tea leaves”) certain steps that could be taken to raise the issue of architecture in a manner that will, in the Trumpian style, explode some heads.

They are:

1. Appoint a traditionalist as chief architect of the General Services Administration, which oversees all federal buildings and building projects. When President George W. Bush appointed Notre Dame’s Thomas Gordon Smith, the design elite went ballistic and the offer was withdrawn.

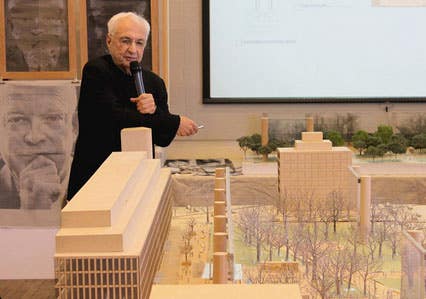

2. Call for a new design competition for the memorial to President Eisenhower. The design by Frank Gehry - who has a feud with Trump - would be an insult to Ike. Canceling Gehry’s design would boost the style wars onto the front page.

3. Back the proposal to rebuild Penn Station as it was originally built in 1910 by the firm of McKim, Meade & White. This is infrastructure with pizzazz. Start making American great again by making New York City great again.

These steps would require no new legislation and no new expenditures. Further steps could be taken as part of Trump’s proposed infrastructure program. He should read the recent speech by John Hayes, Britain’s new transit minister, titled “The Journey to Beauty.” (My AHAT blog post “Transport official on beauty” links to it.)

It is certainly true, as Adam points out, that architecture is “a supertanker that will take a long time to turn.” But the idea of architecture is not necessarily a supertanker, and can be turned, if not on a dime, more swiftly than a supertanker. It is incontestable that most new buildings are what most people would call “alien spaceships.” They get built because traditional architecture is excluded, public opinion is suppressed, and the establishment keeps a very heavy thumb on the playing field for major commissions. As Adam put it, major commissions

"are of a scale that they will be designed by an architectural profession that despises tradition and they will be allowed by bureaucrats who, often as not, belong to the same or associated professions and, being professionals, will always defer to the authority of other professionals."

Imagine the thumb lifted and the playing field leveled for major commissions, so that the development process in cities around the country welcomed traditional design proposals along with the modernist proposals it has favored for half a century. I’d be willing to bet that the supertanker would surprise everybody with its sudden maneuverability, making America (and the world) look great again faster than anyone today could possibly suspect.

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.