Carroll William Westfall

Tradition Preserves Liberty

Tradition preserves liberty, a natural right and endowment of human nature along with life and the pursuit of happiness. Liberty allows an individual to control how he uses those endowments, and it allows the political order to protect them for each individual.

Every political body (civil or religious) since early antiquity has protected these qualities of human nature in different ways mounted on a spinning calliope until, three hundred or so years ago, the present iteration entrusted to protect them and to serve each individual’s human flourishing arrived. Our political order stands on traditions of governing and theorizing that began in ancient Greece, tradition that in each age and nation absorbed innovations to serve new circumstances and to absorb new knowledge and new insight about the order that humankind shares with Nature. This reciprocity between humankind’s relationship to Nature and the dynamic reciprocity between tradition and innovation constitutes the very heart of the classical tradition.

In 1776 when the colonists could not find a remedy for the British King’s tyrannical suppression of the traditional liberties of Englishmen, they took command of their political order. At Gettysburg Abraham Lincoln referred to it as “a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” The men died in Pennsylvania to assure that this new nation, “shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

In 1776 as in 1863, this new nation rose from the solid foundations of traditions that use the authority of government to guarantee the rights of each individual, traditions now amended to allow every individual liberty to participate in the exercise of that authority to promote the common good that benefits each individual.

Our democratic republic is one of many different forms used across history for organizing authority. Among them and leaving aside theocracies handed down by divinities, ours goes back to the experiences and theorizing of ancient Greeks who identified rule by one as a monarch and by the many in a democracy with various assortments of the few between those exremes. The American Founders were marinated in the rich sauce of the Greco-Roman political and legal structure as well as the experience of other nations and of their own experience in governing their affairs within a political tradition that included the unique overlay of English common law and now with new insights and knowledge gained by their exploring ancient texts. All through this long and deep history two unwavering lodestones provided guidance: the role of the reciprocity of tradition and innovation in guiding the affairs of individuals and nations, and the role of the four fundamental tasks of governing whether in a family or a nation: to frame wise laws, to execute them honestly, to render just decisions based on the laws, and to provide for the common defense.

These four tasks constitute a nexus that is congruent with the order of Nature, the source that the 1776 Declaration refers to as “Nature or Nature’s God,” which locates the nation’s civil order in the heart of the Greco-Roman natural law tradition (natural law must not be confused with the newly emerging empiricism seeking laws of nature that are rendered in formulaic interpretations and apply to change in nature’ physical realm).

Natural law calls on performing various duties to promote human flourishing, and these entail two levels of organization, one of institutions, the other of their subordinate arrangements. Different times and places organize these differently to embody the experience and the traditions of a people, traditions that are constantly adjusted to incorporate new knowledge and changing circumstances. Institutions are primary: they fulfill purposes that address the moral order of Nature that supplies the standards we seek in the good in what we do, the true in what we know, and the beautiful in what we make. Purposes are enduring; their ultimate goal is to assure justice and protect liberty. Subordinate arrangements serve the functions that facilitate achieving those purposes. They range from markets that facilitate the exchange of goods to roadways that facilitate the movement of goods and people as they play their roles in contributing to the common good. The purposes of institutions endure while functions are constantly amended in order to better serve institutions’ purposes.

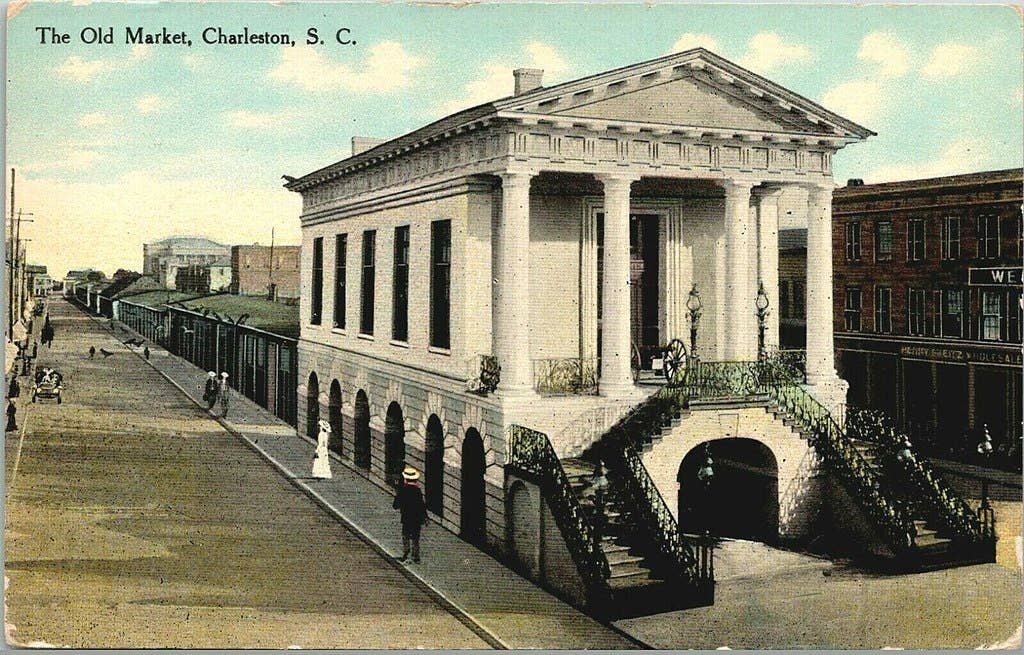

To fulfill purposes and providing the ancillary functions, a civil order builds buildings and assembles them into the urban and rural setting places where individuals may engage in the political order’s activities. Axiomatic in traditional architecture is that the more important the purpose the building is to serve and express, the more fully it will draw on the formal conventions of the apparatus of architecture in rendering that service to assure that the role and appearance are calibrated relative to the importance of the purpose or function it serves. In the city devoted to justice, in each building purpose trumps function every time and provides a clear identity of the purpose and relative importance of the purpose in the political order.

About a century ago this role for buildings came under attack. Purpose and function were conflated, and soon thereafter, functions assumed primacy with displays of industry’s new materials and of architects’ commitment to the newest fashions. This undermined the traditional, primary raison d’être that political orders build buildings, which is to serve a civil purpose or fulfill a purpose’s necessary functions. As functions serving commerce gained an ascendency, builders and architects increasingly treated buildings simply as things with disregard for their contribution to or role in serving the common good. Architecture’s immersion in Modernism has now largely alienated the general population that is composed of individuals who retain respect for the traditional roles for buildings that make urban places where they can enjoy the liberty to pursue their happiness.

As these once-new buildings become old and obsolete, they are replaced with newer versions of this new architecture. Meanwhile, popularity grows for adapting old buildings that served now obsolete functions, giving them new functions and keeping them as prized places in urbanism. These rescued old buildings and new ones that extend the traditions they embody do what Modernist buildings cannot do: they evoke the shared past of a people united in a political order. The formal sources for these old and new traditional buildings came perhaps from England, perhaps from the Greco-Roman tradition, but always with distinctively American qualities. Along with others, they make a distinctive urban place with a familiar, identifiable demarcation between important institutional purposes and the various functional activities serving them. These buildings are traditional, yes, and also new: across the centuries and down to today, the tradition that guides their designs has absorbed the innovations that have adapted it to the time and place of the buildings’ construction. While freshening urbanism’s beauty, just as our political order does within the framework of natural law, as it connects our present with a valued past that reaches back more than two thousand years, at the same time pointing forward to continued service in fulfilling the purposes of our old, new nation.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.