Carroll William Westfall

The Value of Tradition in Urbanism

Urbanism is what we build to serve our needs and desires in families and neighborhoods and on up in scale to cities, states and nations. It is the grandest, most complicated, complex, and extensive thing we build, but we underestimate its role in our lives, and it is tradition that makes urbanism valuable for us.

Urbanism is composed of many different parts that make a whole. Its construction does not simply happen. To build it right, people must work together in communities with common interests. These exist in various sizes with the most important being the all-encompassing community that offers the security we need and that facilitates our pursuit of happiness. In this community we practice the art of living well together, the art whose name is politics, not in the sense of partisanship but with the meaning derived from the Greek word polis.

The Romans called it the city, the word that referred to the organization of the political life and a word like many other they gave us that we use – family, community, state, nation, not to mention Senate, etc. They also gave us the word urbanism to identify the physical place where a large community works together for a common end, that is, where a city practices that art.

We tend to use the word city to refer without distinction to a political jurisdiction or to its urban setting. This lets us forget that urbanism is the produce of acts intended to serve the lives of the city’s citizens and residents and that it is built of pieces conscientiously assembled to make, to reform, to renew, and to extent a whole physical place that will facilitate our achieving our highest and best aspirations.

That purpose has increasingly taken second place to the more mundane concerns of commerce, transportation, sanitation, and so on that are necessary but not sufficient for living nobly and well together. The result is too often something neither as useful as it ought to be nor as beautiful as it can be. In a series of blogs here I will be sketching some practices that will help us again make urbanism that we can be proud of.

Laws, customs and traditions bind us into communities with the city at its center, and the urbanism we build both serves and expresses what communities value. In the west’s Greco-Roman-Hebraic tradition ideas of the good city have guided people with Plato and Aristotle being the most influential. For Plato the city is man writ large, the city makes the man, and the good city, the best city a community can build, imitates the perfect city, which mortal men cannot know completely and can only approximate in how they live. It is the ideal that inspires them to seek the best possible civil life.

Aristotle, always more down to earth, described the actual practices of the best possible city. Being naturally sociable, we form families to assure humankind’s perpetuation. Families assemble into communities to establish a market where they exchange their skills to assure their security and livelihood. And these communities then combine to practice the art of politics to achieve the good life.

The good life we seek is based on justice, which allows each individual to enjoy that which he merits by nature. We seek justice by using the unique endowment of the human species, which is the ability to combine reason, memory, and skill in the pursuit of happiness as individuals engaged in the life of the good city. Its urban counterpart in the beautiful city in which each of its parts and their assembly into a whole serves the city’s good purposes. When well built, the whole and the parts, whether buildings, streets, or skylines, are the best possible examples of the kinds of things they are.

People are born into families but willingly join with others to make a good community.

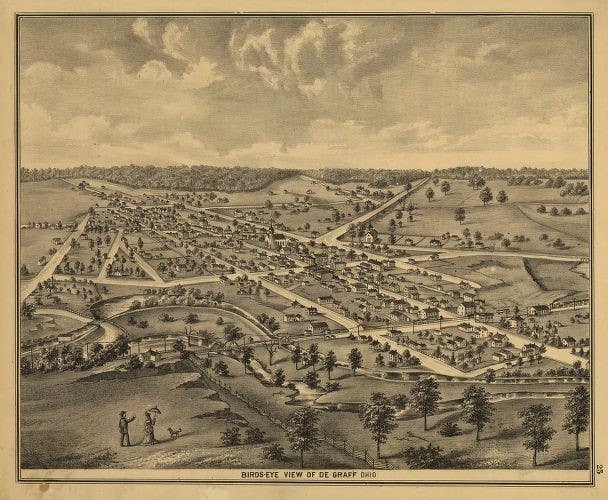

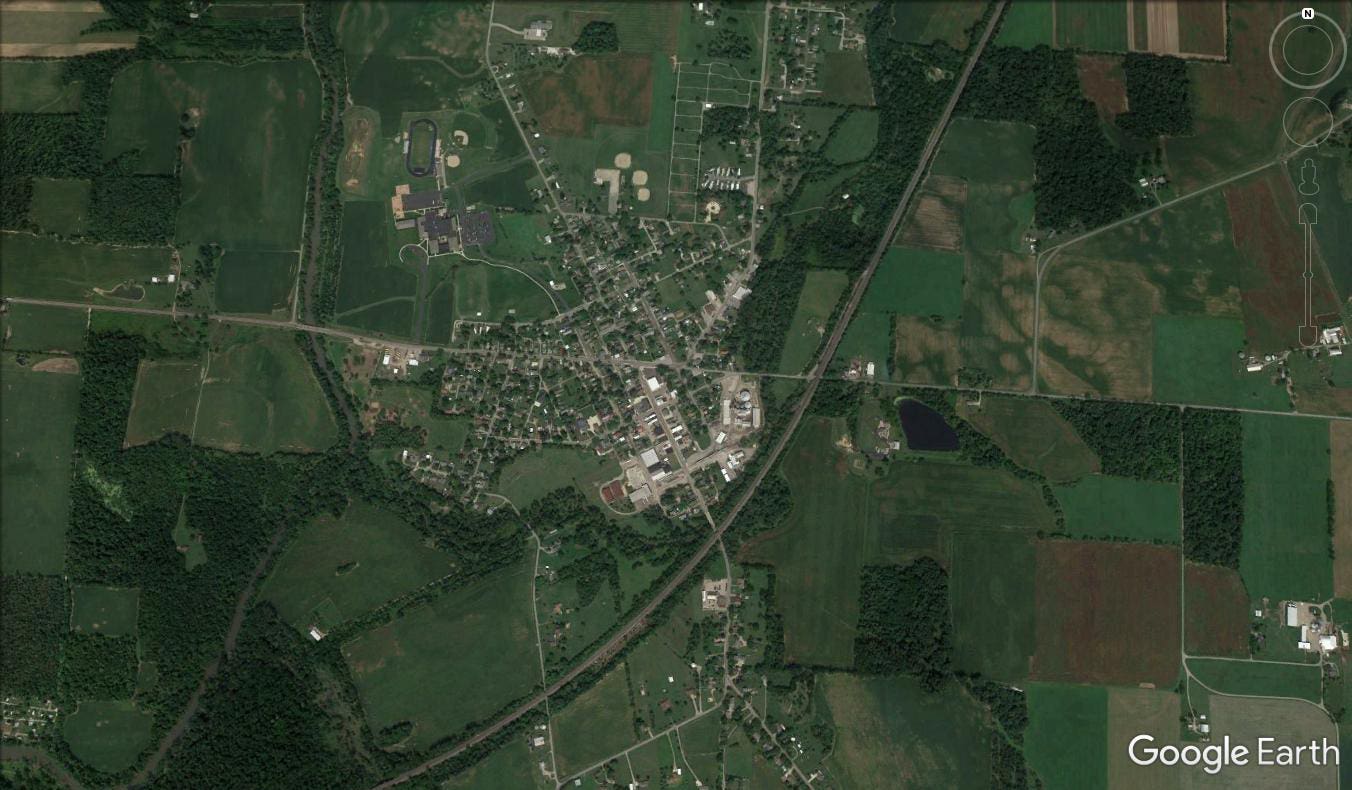

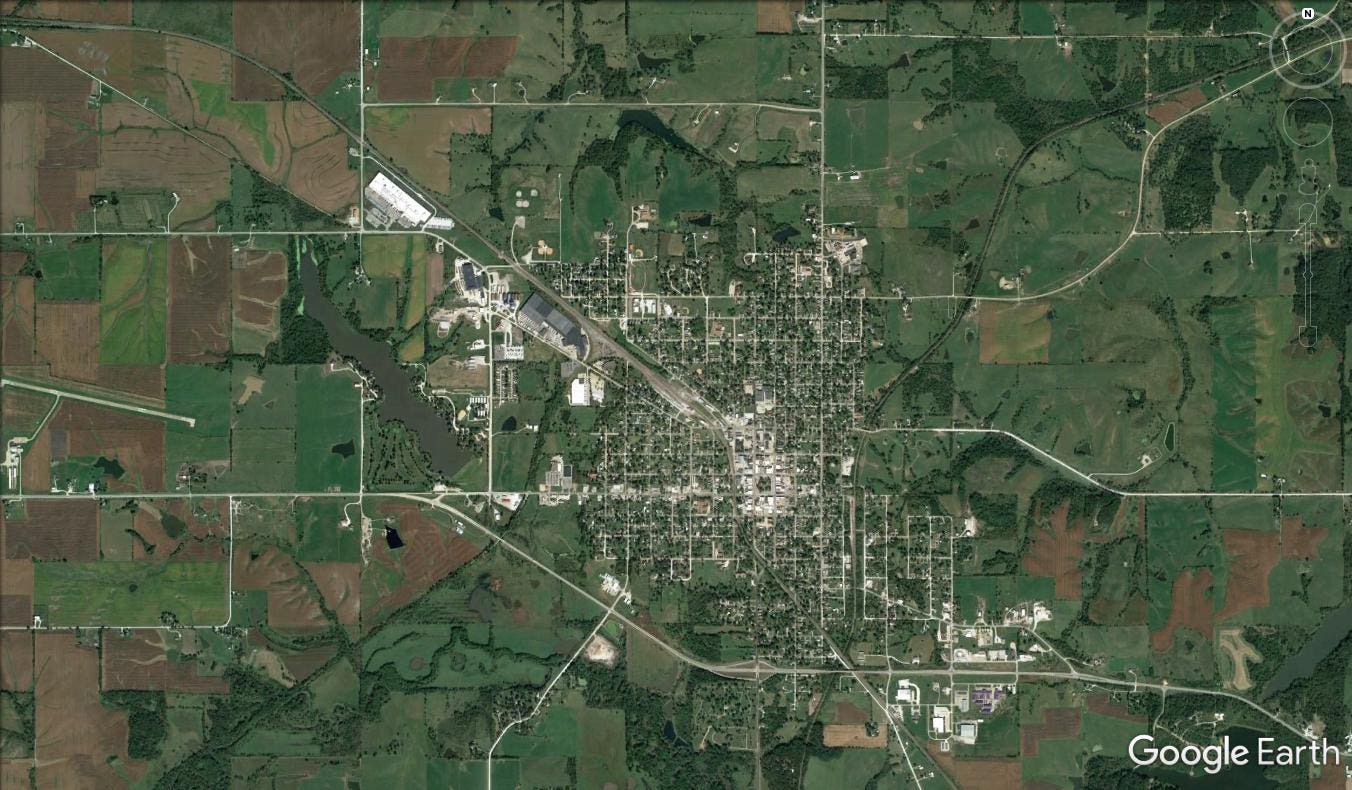

These can be as varied as bowling leagues, hiking clubs and choral societies to religious congregations of monks, nuns or lay people. They can range from professional organizations, service clubs and PTAs and on to markets and cities, the most valued one that Aristotle listed. All of them need physical places, with the most important among them the family’s home, the neighborhood with its market, and the collection into an interconnected order that makes their capstone, the urbanism of the city.

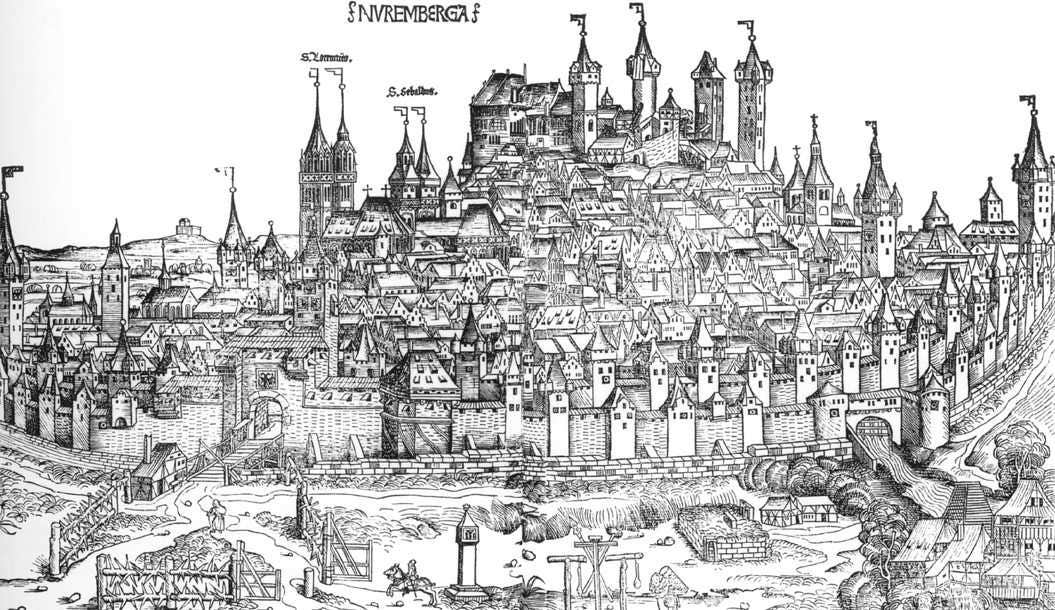

Temples conspicuously dominated the ancient city in both its urbanism and its commitment to the gods. The Romans added the great public buildings whose great ruins we admire today. The medieval city featured the complement of cathedral and smaller churches with subordinate walls, a castle and a city hall in free cities. Houses and other buildings serving lesser roles were scanted.

That changed in the Renaissance when people began paying as much attention to enjoying the beauties of this world as to those that Heaven promised. Theorists and architects began adding to religious buildings the secular buildings and the streets and squares they defined, and they began treating the city as a whole, material and civil organism that served and expressed he city’s aspiration to be a good city where people used the art of politics to achieve justice. The Renaissance also awakened people to the roles they could, and needed to, play in the city’s life, and this realization eventually led to principles on which our nation is founded.

When we expanded the traditional practice of politics in our innovative, federated nation by putting the political life in the hands of We the People we haltingly and steadily developed a traditional and innovative architecture and urbanism to serve and express our aspiration.

Our home-grown traditions in urbanism have been weathering difficult times, but in our cities we continue to commit ourselves to seeking justice for all. This requires that we recognize that urbanism is architecture at a bigger scale and built over a longer span of time. And it requires a commitment to recovering and using the traditional practices that are the best guide for the innovations that address changing circumstances.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.