David Brussat

The Providence Arcade Survives as Oldest U.S. Mall

Is there a 5-second rule for landmarks as for food?

This month’s blog is a prepublication excerpt from my book Lost Providence, written for The History Press and scheduled for publication next April. The book expands on a column I did for the Providence Journal, “Providence’s 10 best lost buildings,”and traces the history of change in the looks of a remarkably beautiful city. This excerpt from the chapter “Lost: Westminster Congregational Church”discusses the Providence Arcade, which does not get its own chapter in the book because it has not been lost - though it has had some close shaves.

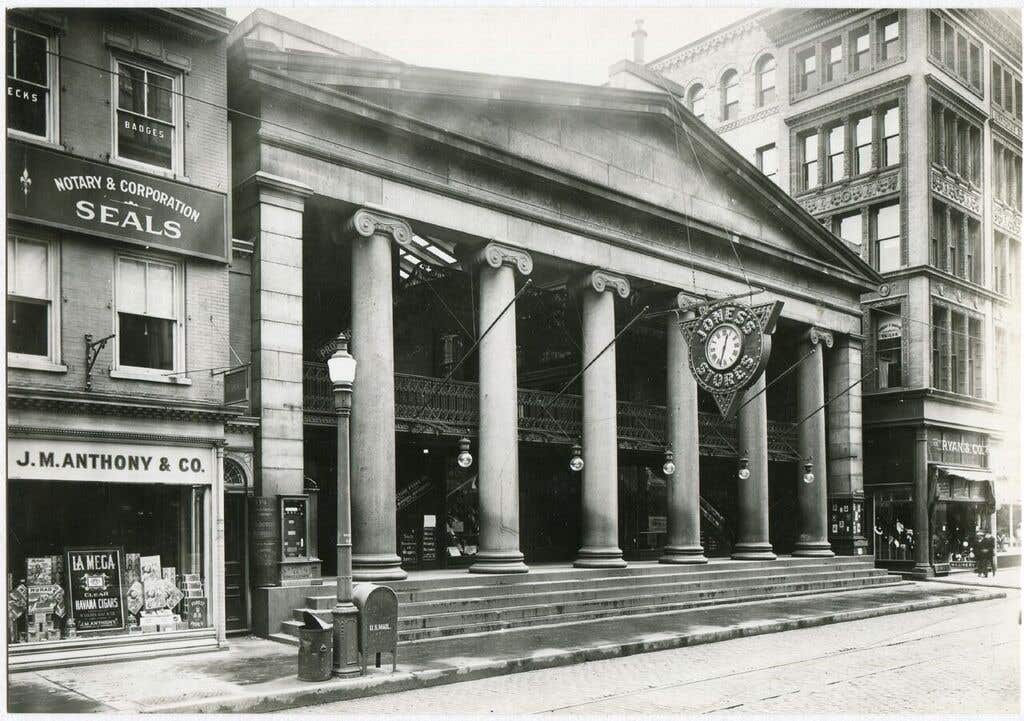

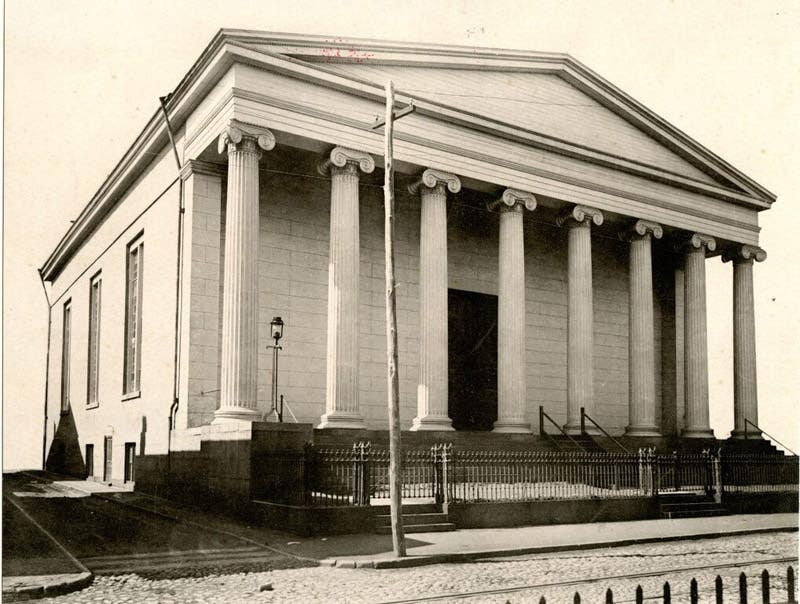

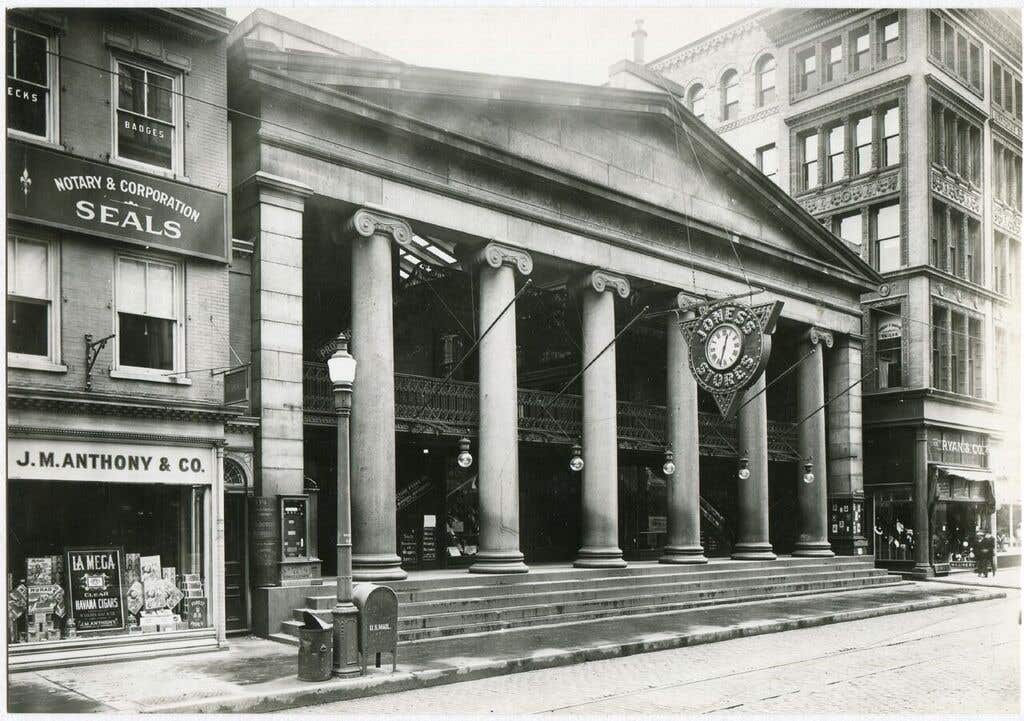

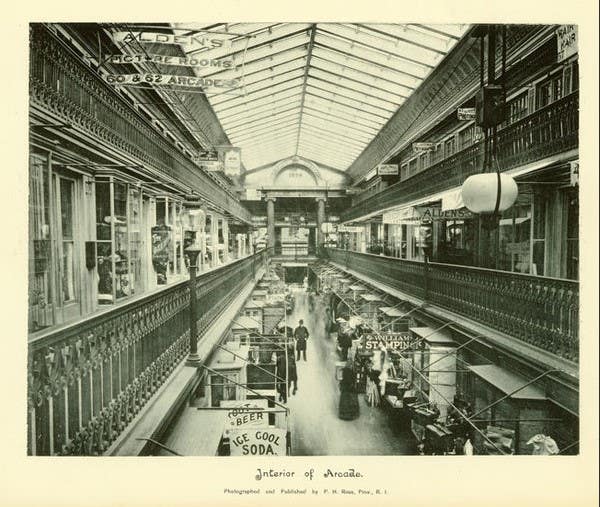

When Providence Place opened in August 1999, the city could momentarily boast having the nation’s newest mall and its oldest – the Arcade. This building, in the form of a Greek temple reaching through the entire block, [designed by Russell Warren and James C. Bucklin and] completed in 1828, is among the very early commercial structures in what was to become downtown Providence. The six Ionic columns of granite at either end were, upon their erection, the largest monoliths in the United States. The Arcade would deserve a chapter of its own were it a lost building, which thankfully it is not. However, this chapter on the Westminster Congregational Church, with its original temple front and eight columns, represents a splendid opportunity to slip in a few remarks about the beloved cathedral of commerce.

A local parlor game could be invented in which players would cite contemporary newspaper and magazine references to the Arcade as the first indoor shopping mall in the nation. The Arcade is America’s oldest indoor mall. It was not the first. That distinction belongs to either the New York or the Philadelphia arcades, both of which were designed by John Haviland and completed in 1827, a year before the one in Providence. All three were inspired by London’s Burlington Arcade, which opened in 1819 (and still exists). The one in New York was an immediate failure, demolished after just a few years; the one in Philadelphia remained in business until it was demolished for a department store during the 1890s. Again, the Providence Arcade is the oldest, not the first. The words are not synonymous.

After 1870 it may be assumed that Rhode Island’s robust manufacturing expansion and rapid population growth allowed the Arcade to prosper. Good times did not last. Prosperity stumbled in the period encompassing Depression, two world wars and the gathering flight of the state’s textile industry to the South. (The map reprinted in this book’s prologue, showing Providence as “The Center of Northern Industries,” with trade links to other parts of the country and the world, seems unfazed by the ominous “Great Textile District of the South.”) The Arcade joined other downtown businesses in the slow general decline.

Saving the Providence Arcade

In 1944 plans to demolish the Arcade for an office building startled citizens and perhaps generated the first surge of regret at the growing status of demolition as a tactic of civic redevelopment. The 1956 founding of the Providence Preservation Society was still a dozen years in the future, but socialite John Nicholas Brown led an effort to block the attempt to raze the Arcade, ending with its purchase by the Rhode Island Society for the Blind. Rhode Island builder Gilbane Properties bought it in 1977 and in 1980 financed a renovation by Irving B. Haynes & Associates.

Visitors to the Arcade in the mid-1980s and beyond, including this writer, enjoyed what seemed to be a healthy selection of shops, lunchtime eateries, restaurants and evening entertainment venues (such as the comedy club Periwinkles). Its alleged retail difficulties led, nevertheless, to a brief ownership by Johnson & Wales University, which sold it to a development firm experienced in the management of historic buildings. Yet Granoff Associates put in place a business model of raising rents and evicting retailers until only 13 remained. The firm then closed the building, ending, at least in theory, its status as the nation’s oldest shopping mall.

Granoff attempted to find a single lessee, such as a Staples. Failing at that, Granoff hired Northeastern (formerly Newport) Collaborative Architects to renovate the building and, with the advice of the Providence Preservation Society, saved the building’s status as a “mall” by transforming the entire space, placing a dozen niche shops on the ground floor and devoting the two upper floors to residential microlofts, most of them with fewer than 300 square feet of living space. There were more than 4,000 names on the waiting list for the lofts but some of the shops seemed dodgy. At this point, however, downtown still has a mall that looks like a church designed as a Greek temple from both directions.

There must be an architectural landmark equivalent of the Five Second Rule, whereby those who drop food on the ground can eat it if they pick it up within five seconds. (Is that the average time it takes for a bug or a germ to invade the morsel?) The Arcade was closed in 2008, and remained closed for about five years until it reopened in 2013. Nobody grumbled that the Arcade could no longer claim to be the nation’s oldest mall. So it appears as if a historic building does not lose its landmark status so long as it reopens within five years.

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.