Patrick Webb

The Metaphysical Craftsman

As we continue in the craftsman's philosophy series we leap headlong into the world of metaphysics, the study of the very nature of existence. A broad and deep branch of philosophy with many correlations to craft that we will revisit time and again. The ambitions of this essay are modest, an opening inquiry into matter, form and change; however, I would assert quite relevant to the craftsman working in applying designs and transforming materials.

Mom and Pop as Agents of Substantial Change

Sexuality is an inescapable fact of life and human existence. Well, who's looking to escape it anyway? Most if not all ancient peoples extrapolated the observations of reproduction and growth inherent in human, animal and plant sexuality to grander explanations of birth, change and death and rebirth of all things. There were underlying forces, masculine and feminine divinities in most cases attributed for everything that we sense as constituting the natural world, living or inanimate.

Greek philosophers, as early as the 5th century B.C.E., began to construct and codify explanations that continued to draw from natural observation but largely eliminated what we might call superstitious elements or appeals to the divine. Notable amongst these philosophers was Aristotle. He asserted that sensible objects consisted of form applied to matter. Departing from his mentor Plato, he denied that form could have a distinct existence as a purely ideal concept, rather he claimed that form by necessity was embodied in and inseparable from matter, physical reality.

Aristotle established a school in the pre-existing Lyceum of Athens that was quite successful, open on and off for over 200 years before the Roman general Sulla sacked the city. Fortunately, the Romans preserved most of Aristotle's work and the aforementioned philosophy was to take root in Roman intellectual culture. Interestingly, our English words for father and mother come directly from the Latin words pater and mater respectively. We likewise have inherited the words pattern (form) and matter from the same Latin root words. Substance, so it was purported, results from the masculine pattern imposed upon the feminine matter. This was said to occur at a primary (might I suggest quantum?) level. Most of what is identified as objects would be agglomerations or compounds of elemental substances.

From this imposition of pattern upon matter there arises the Latin natura, something born, the obvious analogy being of a father and mother begetting children. However, how does one account for change with this viewpoint? It almost appears as if something arises from nothing which sounds absurd. Aristotle proposed that while matter is in fact static and permanent, form has intrinsic dynamism. At the same that time form or pattern has an actuality that defines matter, there exists an inherent potentiality, the possibility of transformation.

Causation as Creation

Although the aforementioned explanation of form teases what is apparent from our senses, that change is possible, it doesn't explicitly reveal how or why it occurs. Aristotle thought that having the answers to these questions was directly tied to real, causal knowledge. In his view we can't truly know an object simply from superficial observation alone. Real knowledge comes from a deeper understanding of what causes the object of interest to be as it is. He was trying to frame all of nature, including human activities into a teleological model, one that has a “telos”, an intended end goal. To explain this, Aristotle went on to address such inquiries through his description of the four causes of which I'll adopt and personalise his example of substantial change as illustrated by craft, in the specific case of carving an Ionic capital out of stone.

Material Cause

The material cause, as you might expect, is one of fundamental composition, meant to satisfy the question, "What is it made of?" It is the object of material permanence that foreshadows a formal change. In our craft example, you can see me at right outside of Austin inspecting an exposed bed of Texas limestone.

Formal Cause

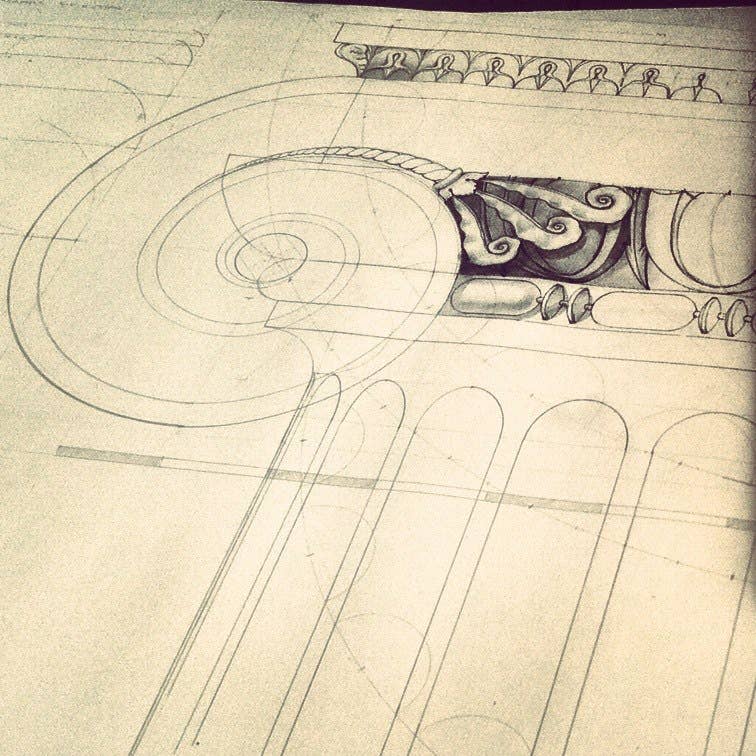

Here we must be careful. There is a temptation to allow desires and intentions to cloud the meaning of formal cause. However, we must remember that Aristotle intends a universal system that explains natural change as well, where such intentionality is thought to be absent. Here we answer the question of "What kind of thing is it to be?" This often refers to a change in an object’s shape as in our example. For the craftsman this occurs in the process of design, originally initiated as an archetypal example in his mind even if influenced by a treatise or example. The potential inherent in material, the taking on of a specific form will be often illustrated in drawings such as the layout of one of the volutes pictured here.

Efficient Cause

"By what means does the transformation occur?" At this point we engage with technique, the steps required to apply form to matter, resulting in formal not material change. Technique is a specifically applied knowledge; it is where practise departs from theory. In our particular case it is the applied knowledge of mallet and chisel as exerted upon the "matter" of limestone to impose the "form" of a volute.

Final Cause

This is certainly considered to be by Aristotle a primacy among causes. The final cause answers: "What is the raison d'être? Essentially, what is the purpose?" For the purposes of nature, the thrust of his arguments surrounding final causation are in favour of an aspiration in all things to return to the unmoved mover, the divine source. I'll leave those aside for the moment and consider the craftsman's condition.

Certainly, the "end product", in our case the Ionic capital, is an external manifestation of human expression or intention which Aristotle does not preclude. In fact, the desire for final outcomes in art, craft and architecture is acknowledged as generative in the development of formal and efficient causes. With purposes in mind beforehand, humans will create new forms and new techniques, sourcing materials having the potential to realise them.

Aristotle’s perspective and really the entire study of metaphysics came under withering criticism during the Enlightenment. Particularly, the supposed moment of causation was denied as something that could never be observed, as such impossible as an object of knowledge and subsequently a rationally pointless subject of scientific enquiry. However, this runs counter to our daily subjective “experience” of causation, our sense of meaning and order in the world. Typical of craftsmen, their knowledge of reality is not literal (best expressed in words) rather intimate, the world as a forum for active engagement. They don’t know the world in the sense of knowing what, like the categorisation of an object. Instead it’s more of knowing who, like one might come to know a friend or lover. This series will continue to do what’s possible to reconcile these two ways of knowing or philosophies, doing its best to convey in words what one experiences as a craftsman.

My name is Patrick Webb, I’m a heritage and ornamental plasterer, an educator and an advocate for the specification of natural, historically utilized plasters: clay, lime, gypsum, hydraulic lime in contemporary architectural specification.

I was raised by a father in an Arts & Crafts tradition. Patrick Sr. learned the “decorative” arts of painting, plastering and wall covering as a young man in England. Raising me equated to teaching through working. All of life’s important lessons were considered ones that could be learned from the mediums of tradition and craft. I found myself most drawn to plastering as I considered it the richest of the three aforementioned trades for artistic expression.

This strong paternal influence was tempered by my grandmother, Geraldine Webb, a cultured, traveled, well-educated woman, fluent in several languages. She made a point of instructing her young grandson in Spanish, French, formal etiquette and opened up an entire worldview of history and culture.

After three years attending the University of Texas’ civil engineering program with a focus on mineral compositions, I departed, taking a vow of poverty, living as a religious aesthetic for a period of seven years. This time was devoted to clear reasoning, linguistic studies, examination of world religions, exploration of ethics and aesthetics. It acted as a circuitous path leading back to traditional craft, now imbued with a deeper understanding of interconnection in time and place. I ceased to see craft as simply work or labor for daily bread but among the sacred outward expressions of the divine anifest

within us.

From that time going forward there have been numerous interesting experiences. Among them study of plastering traditions under true masters here in the US as well as in England, Germany, France, Italy and Morocco. Projects have included such high expressions of plasterwork as mouldings, ornament, buon fresco, stuc pierre, sgraffito and tadelakt.

I’ve been privileged to teach for the American College of the Building Arts in Charleston, SC, where I currently reside and for the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art across the US. “Sharing is caring” – such a corny cliché but so true. I hardly know a

thing that hasn’t been practically served to me on a platter. I’m grateful first of all, but now that I might actually know a few things, it becomes my responsibility to be generous as well.