Clem Labine

The Bare Brick Mistake Will Not Die!

Like a vampire that won’t stay dead, the bizarre urge to strip plaster off brick walls walks the land once again. The yearning for “exposed brick” was a renovation fad in the 1960s and '70s, but I thought the silliness that begot this folly had been laid to rest.

As early as 1973, in the pages of Old-House Journal, I had outlined both the aesthetic and practical reasons for leaving plaster on brick walls. And, for a while, the craze seemed to have subsided. But just as the full moon causes Dracula to rise once again from his coffin, so The Bare Brick Mistake has returned to cast its spell over a new generation of renovators.

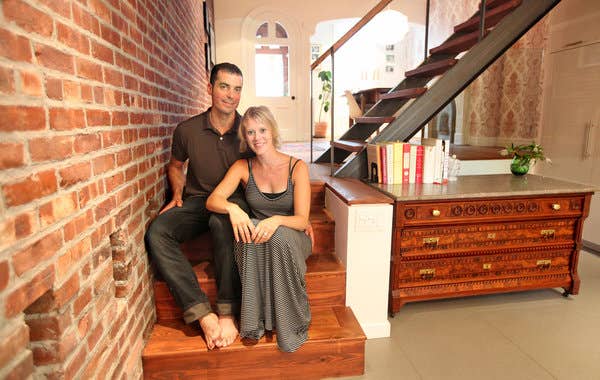

My colleague Paul Kitzke called my attention to the latest egregious example. This article in the New York Times tells the story of David and Liz and their renovation of an abandoned wreck of a townhouse in Brooklyn. The couple seems sensitive to the history of the house and treasures what little remains of its original architectural details. But – in a triumph of fad over common sense – they chipped the plaster off their brick walls.

The reporter from the Times described the result in glowing terms: "The brick hidden behind plaster walls was exposed, as was the brick beneath the stucco on the facade." The writer makes it sound like some sinister fellow deliberately hid a beautiful brick wall behind a coat of plaster as a deliberate act of aesthetic sabotage. Nothing could be further from the truth:

Plaster was originally applied to those brick walls for very sound, practical reasons

1. Old townhouse party walls are made of soft, porous brick sloppily laid up because the masons knew the walls would be covered with plaster.

2. Once stripped, the exposed brick both collects dust and sheds its own mortar and brick particles.

3. If the bare brick is covered with a sealer to retard exfoliation, the sealer imparts a plastic-looking sheen that detracts from the desired natural, rustic appearance of the brick.

4. The plaster acts as an extra layer of insulation and protection in case of a fire in the row house next door.

5. Worst of all, the lack of plaster greatly increases sound transmission from the adjacent building. If your neighbor also exposes the brick on his or her side of the party wall, you can conduct a conversation through the bricks.

David and Liz may also discover that the stucco on the building’s exterior had been applied to prevent water infiltration through the outside brick caused by wind-driven rain.

The passion for exposed brick had largely vanished by the end of the 1990s as the various problems posed by bare brick became apparent, and many realized the whole fad was a mistake. However, these manias run in cycles, and it looks like the lust for exposed brick has risen from the dead once again. Thus, a whole new flock of renovators is doomed to discovering bare brick’s many nuisances all over again. When that happens, perhaps The Bare Brick Mistake can be interred forever -- with a stake through its heart!

Clem Labine is the founder of Old-House Journal, Clem Labine’s Traditional Building, and Clem Labine’s Period Homes. His interest in preservation stemmed from his purchase and restoration of an 1883 brownstone in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn, NY.

Labine has received numerous awards, including awards from The Preservation League of New York State, the Arthur Ross Award from Classical America and The Harley J. McKee Award from the Association for Preservation Technology (APT). He has also received awards from such organizations as The National Trust for Historic Preservation, The Victorian Society, New York State Historic Preservation Office, The Brooklyn Brownstone Conference, The Municipal Art Society, and the Historic House Association. He was a founding board member of the Institute of Classical Architecture and served in an active capacity on the board until 2005, when he moved to board emeritus status. A chemical engineer from Yale, Labine held a variety of editorial and marketing positions at McGraw-Hill before leaving in 1972 to pursue his interest in preservation.