David Brussat

A Tale of Two Library Entrances: Evanston and Providence

In the latest issue of author Gordon Bock tells the story of a masterful architectural righting of a historical wrong at Northwestern University’s. The Chicago firm of won this year’s Palladio in the category of restoration and renovation for its work to reverse the closure of the library’s West Entry. It had been shut after the Deering was demoted by the construction in 1970 of a new main university library in the Brutalist style. Access to the Deering, which continued in operation as a secondary facility, was shifted to an underground passage from the main library. Work to reopen the West Entry of the Deering, restore its lobby and add a new terrace was finished in 2012.

In the latest issue of Traditional Building, author Gordon Bock tells the story of a masterful architectural righting of a historical wrong at Northwestern University’s Charles Deering Library. The Chicago firm of HBRA Architects won this year’s Palladio in the category of restoration and renovation for its work to reverse the closure of the library’s West Entry. It had been shut after the Deering was demoted by the construction in 1970 of a new main university library in the Brutalist style. Access to the Deering, which continued in operation as a secondary facility, was shifted to an underground passage from the main library. Work to reopen the West Entry of the Deering, restore its lobby and add a new terrace was finished in 2012.

The Deering

Designed by James Gamble Rogers, the Deering opened in 1933. “The client’s wish was that there be no visual disparity between the quality of the new work and the original architecture of the Rogers building,” Aric Lasher, president of HBRA, tells Bock, who adds, “Or, put another way, their goal was not to follow a ‘nod to the future and a nod to the past’ approach in introducing modern elements.”

In addition to the project architect, William Kinane Jr., TB lists the key suppliers of the millwork, carving, ornamental metalwork, stone fabrication and lighting necessary to carry out the client’s wish. Their work’s excellence is fully evident in the photos by Mark Ballogg. Other articles describe more of this year’s Palladio commercial winners; residential winners will be featured in TB’s next issue.

Photographs that show how Deering and the 1970 building relate to each other physically are hard to locate. It must be difficult for the average student on campus in Evanston, IL, where Northwestern is located, to grasp just how the main library managed to shunt the elegant Deering to the side. The main library looks like a big fat disco collar hanging open around the neck of the poor slob of a campus. It is a major embarrassment. It was an error typical of the era, now thankfully rectified by the university with the help of HBRA. Today, Northwestern’s online library sites show a photo of the Deering in representations of the main library.

The Providence Public Library

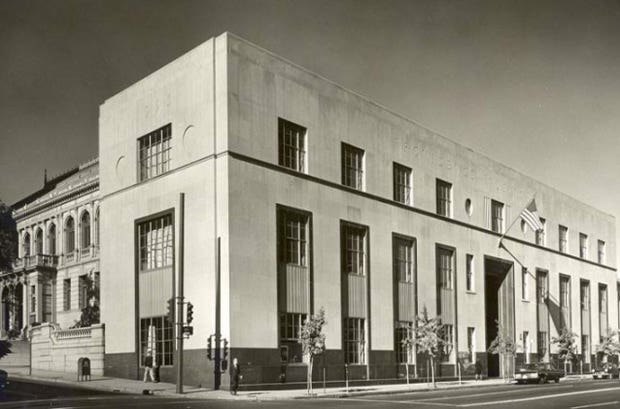

It may be even harder to get one’s mind around how, no more than a decade ago, the Providence Public Library managed to trade so far down as it did by switching from its original Beaux Arts entry on Washington Street to the one it now uses via the basement of its 1954 modernist addition on Empire Street.

Historically, it’s gone back and forth. The library in Providence was inspired by the library completed in 1553 on Venice’s St. Mark’s Square. In Providence the original Beaux Arts building, designed by Stone, Carpenter & Willson, opened in 1900, the same year as McKim Mead & White’s Rhode Island State House. The main entry on Washington Street served well for half a century.

A Moderne addition opened in 1954, occasioning its first entrance switcheroo to Empire Street. In the 1990s, a historical rehabilitation shifted the entrance back to Washington Street. In the first decade of this century came another switch. The library tried to snooker the city: its management set up a new branch in the basement, supposedly warranting a second spigot of funds from the city. As if to support its argument, the entrance was switched back to Empire. The naked stratagem failed, and blew up the long relationship between the city and the library (a private institution in spite of its name).

To make up for lost funding, the library has now turned itself into Party Central. With a caterer managing the building after hours, the library rents itself out to organizations that host posh meetings and celebrations in its nicer spaces. Attendees are invited to use the Washington Street entrance – newly reopened, but only for the “1 percent.”

A decade of occasionally wagging my finger at the library and its administration has drawn no challenge to my characterization of the above circumstances. I do not blame the institution for trying to cadge more cash from public coffers - a library could hardly manage to waste it more egregiously than most agencies. Nor do I blame the library for its party-hardy rebound after its bogus branch failed to bring home the bacon. But it remains inexcusable for the library to rob the public of its stylish 1900 entrance - with what may be the most gorgeous handicap ramp in the history of the world.

Architects sometimes can right historic wrongs. HBRA helped Northwestern University do just that in 2012, and now will take a bow for its good work at the Traditional Building Conference celebration in New Haven on July 19 of the 2016 Palladio Award winners. Is it in the cards for the Providence Public Library to someday win a Palladio for righting its own wrong? Let us hope so!

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.