Carroll William Westfall

Straight Talk About Traditonal Architecture

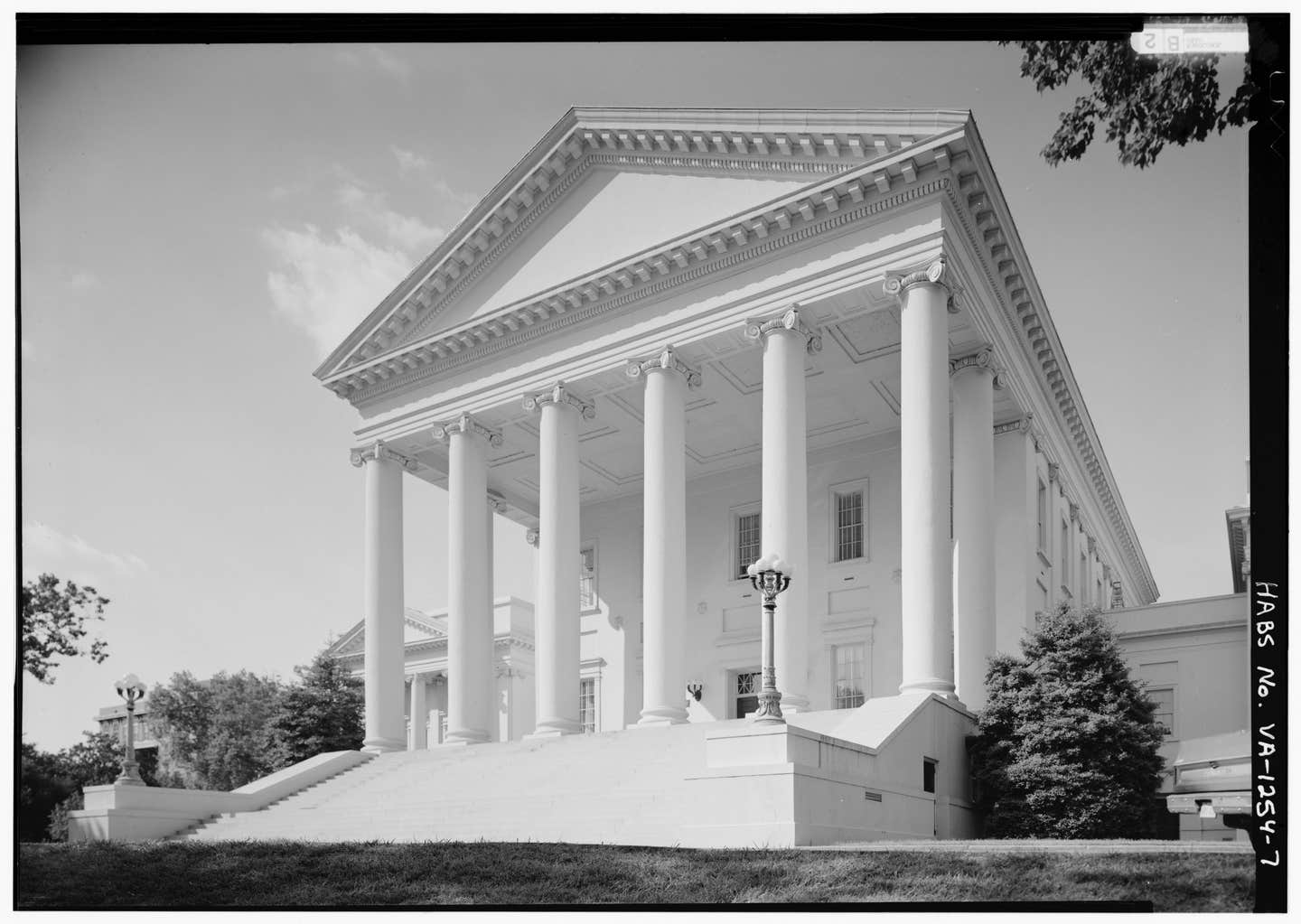

In the last month of his presidency’s Donald J. Trump issued an Executive Order for giving preference to new federal buildings fitting in with the formal traditions of the nation’s classical architecture and establishing a citizen’s advisory panel for vetting proposed designs. I supported the proposal in an Opinion titled “Beauty, Traditional Architecture, and Unity” in 2021 (Jan. 26; updated Feb. 23). Joe Biden rescinded it in the first days of his presidency, but the proposal has reappeared as legislation introduced in the Senate and House with little hope for success.T Jefferon , Capitol Richmnd, VA, 1784 (HABS Photo)

The EO received considerable attention that pitted Modernism against classicism with both treated as vehicles for partisan ideologies. Modernists, who dominate the culture of architecture composed of architects, developers, financiers, cultural leaders, academics, journalists, and critics, were vociferous and vitriolic while those supporting traditional architecture were more measured and careful, perhaps being reluctant to appear to be supporting a partisan position they, like myself, do not endorse. The issue is important and needs to be well aired.

The issue concerns federal buildings, which should not be subjected to partisanship. They may be likened to civil servants and elected and appointed officials who are to fulfill their appointed purposes in advancing the nation’s common good without partisanship. They are partisans when the seek election and when they promote their party’s program in legislative bodies, but partisan positions end when their service to the nation’s business begins.

Public buildings serve and express political purposes, not partisan positions. As Carl von Clausewitz said of waging a war, architecture is “the continuation of policy with other means."Here politics and architecture are united in a tradition that seeks the reasoned order, harmony, and proportionality of Nature for the activities and goals in their respective spheres of service to the common good.

Our nation has enrolled traditional, classical architecture to offer beauty and character commensurate with the common good and the individual pursuit of happiness throughout its history, except for a romantic interlude in the 19th c. and its displacement by anti-traditional, anti-classical styles after World War II. With Modernist styles in ascendancy, in 1962 the General Services Administration, the nation’s builder and property supervisor, imposed “General Principles,” reinforced in the “Design Excellence” Program in 1994 and 2022, mandating that a federal building “must provide efficient and economical facilities … [and] the “architectural style and form” must be “distinguished and … reflect the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability of the American National Government.” Design must flow from the architectural profession to the Government and not vice versa,” and “an official style must be avoided.”

Architects educated in Modernism, ignorant of traditional and classical architectureexcept as a style used in the past, and habituated to this carte blanche license to treat federal buildings a blank canvases for them to practice their art were livid. Those styles belong to the past and do not express modern American ideals, and having the government or a citizen’ panel involved would “stifle aesthetic expression” and abridge their “speech” that, by their claim (but by no court’s ruling), has first amendment protection, two claims that run afoul of the folk wisdom that he who pays the piper calls the tune; for public buildings, we are the paymaster.

The public has not taken well to these non-traditional buildings, especially the newer ones. San Franciscans say their 2006 Federal Building and Courthouse is the ugliest building in their city, but for the GSA it is “A Model of Excellence.” Its architect, Thom Mayne, said that he designs “art for art’s sake architecture.” In speaking of the building he said, “We are a society that is linked to openness of thought, to looking forward with optimism and confidence at a world that is always in the process of becoming. Architecture’s obligation is to maintain this forward thinking stance.”

Those words mimic the ones in the “Guiding Principles” that say that buildings should express “the dignity, enterprise, vigor, and stability” of govenrment. Words like those reveal thatarchitecture has been reduced from offering beauty as a counterpart to the good to serving superficial ideologies of the moment. When tradition guided architects they consulted precedents and made innovations; there was no concept of style. The concept came into use to refer to what was in accord with current or familiar fashions from dress to undercooked green beans. Historians then used it to designate the shared formal qualities of buildings in particular periods—classical or ancient, Gothic or medieval, Renaissance, and Modernist, each with national and temporal subcategories. Each period style carried a unique culture, Zeitgeist, or ideology, making it “of its time” and an alien in any other: classical style buildings do not belong in modern America. This role for period styles installs creativity in the place of tradition and precedent and makes all of its predecessors, even current ones, obsolete. And, incidentally it misuses the word classical or classic, which refers to the best of its kind, as in a classic Modernist building.

This is anti-traditional relativism in its most pure form. It grew from ideas generated in the France of Louis XIV that led to separating beauty from Nature, putting beauty in the eye of the beholder, displacing beauty’s source in the reasoned order, harmony, and proportionality to install it in individual preference and taste or in je ne sais quoi and immune to reasoned understanding: “I like it, you don’t, too bad for you, end of discussion.”

These changes ended the role of architecture as a civic art serving the common good and made it a fine art or beaux art used to flatter patrons, stimulate sublime sensations, or offer delight through romantic or picturesque associations with distant times or places. Thisassociationism soon linked style with ideologies. Ancient Roman styles inspired revolutionaries assaulting monarchs; defeated revolutionaries were confronted with imperial styles; revanchist, imperial regimes used pre-revolutionary styles to cancel the memory of the revolutions and solidify their control (which was the program of the École des Beaux Arts in Paris); anti-classical styles were created by revolutionaries promoting anti-democratic, socialist and communistic utopias as replacements for the regimes that conducted World War I; and those anti-classical styles were allied with technology were nurtured in the Bauhaus to become the Modernism building a capitalist utopia; and of the classical style was used by Nazis and Fascists to promote their evil tyrannies, making the classical the dictator style that Modernists fight.

A Modernism offering a string of words cannot offer the same service to governments that traditional and classical architecture does. Whether democratic, autocratic, or monarchic, governments want buildings that express their authority through the purposes that serve their understanding of the good. Both parties in this interaction between purposes and buildings have always done pursued their goals, mutatis mutandis, by drawing on tradition, the transmitter oftried and tested experience, and on innovation, the adaptation of tradition to current contingencies. Governments always exercise suzerainty over architecture, the former seeking justice and the good, the latter the beauty and the expression of authority for the purposes serving the common good. Its buildings are indifferent to the regime’s form. Public buildings serve and express their government’s purposes with private buildings revealing the character of their builders and owners. When a regime changes, public buildings continue to serve with a new flag flying to signal who’s in charge now, while private ones get a new sign.

Both parties in that interaction work from a common foundation in Nature. This is the Nature explicitly embodied in our founding as “Nature and Nature’s god” and implicitly but unambiguously as the self-evident truths that support our human rights. Our nation’s rich, complex, and orderly ranking of civil orders from national capstones to neighborhood associations. Meanwhile, a variety of new purposes have come into being, and they have been well served by innovations within tradition as public and private builders have invented new technologies and configurations for them. The decorum of traditional architecture within the nation’s urbanism and rural districts identifies their service to the common good and our pursuit of happiness. Most of the state capitols acknowledge their relationship to the U. S. Capitol (it’s dome is cast iron; Imagine!), City halls and the various levels of courts, and libraries and banks and factories take their proper places as well. And a glance can tell that a school is elementary, middle, or high.

American architecture grew not from the new ideas on the continent that led to Modernism as a period style but from the humanist based, traditional architecture that flowed from the Renaissance to England and then to the colonies to build the nation’s new public and private buildings. The nation was captured by the superficialities of romantic, stylistic associationism for several decades in the mid- and later 19th c., but traditional classicism was restored through the triumph of the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 produced by Charles Follen McKim and others. Fearing that American students at the École des Beaux in Paris were succumbing to the monarchic styles it taught they established the American Academy in Rome where Americans could engage with the sources that had nourished their American predecessors.

Modernism’s rise and its identity of architecture with styles put all this at risk. It is notable that the EO and the proposed legislation do not advocate a style; the word only appears when mentioning familiar subordinate styles of the classical: “Neoclassical, Georgian,” etc. But style pervades the opposition. The “Guiding Principles” say that the “architectural style and form” must be “distinguished” and that “an official style must be avoided.” In its reporting The New York Times (Feb. 5, 2020) quoted a draft said “Classical and traditional architectural styles … should be encouraged,” but “styles” was excised from the final EO issued ten months later. Opponents had a field day with what the Times called President Trump’s gilded “design style”and reported that Peter York, author of Dictator Style, said “’Trump’s look, I’d argue, is dictator style.’” In its vehement attack, the American Institute of Architects wrote that the EO “attempts to promote ‘classical’ and ‘traditional’ architecture above other design styles,” suggesting that they are just other styles. And so on.

The EO (and now the proposed legislation) sought a restoration of architecture with beauty and character that can display the beneficent authority of the purposes that serve and express the common good. Modernist styles express divisive partisan ideologies; traditional and classical architecture expresses political ideals and ideas that serve humanity. Yes, the ideals we cherish are unrealizable, which is why we consult Nature and tradition as we tinker with our laws and our buildings to fulfill our hopes for a beneficent future in our pursuit of happiness. The restoration of American architecture is a long overdue non-partisan issue.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.