Clem Labine

Stern Gets Slammed for His Urban Civility

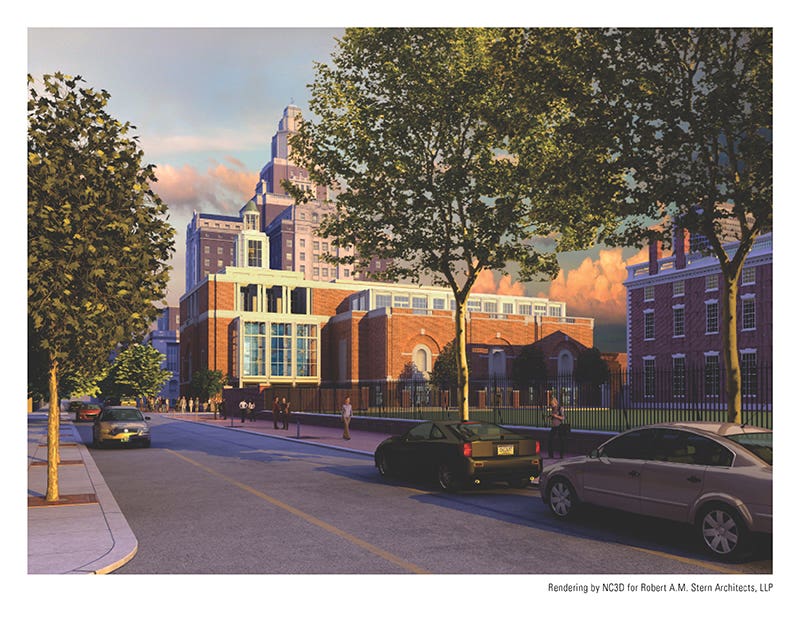

Reviews of the proposed new home for the Museum of the American Revolution show that it’s not just Washington, DC, politicians who are locked in dogmatic struggles. For the new museum, Robert A.M. Stern Architects has produced a traditionally inspired design that fits seamlessly into Philadelphia’s historic core. But, predictably, Stern’s context-friendly proposal has drawn a chorus of derision from ideologically opposed critics.

The museum’s future home faces the Classical 1795 building by Samuel Blodgett that houses the First Bank of the United States. The new museum is also just steps away from other historic sites, such as Independence Hall, Carpenters' Hall, the Liberty Bell Center, the U.S. Custom House and William Strickland’s Merchants' Exchange.

Conscious of the cultural and architectural significance of the museum’s historic neighborhood, Stern’s design employs a restrained Classicism sympathetic to the traditional architecture that abounds in the museum’s historic setting. In further elaborating on his design goal, Stern stated in the New York Times, “What we’re going for is a building that fits in and reflects the general character of the historic district, and which expresses the period of the American Revolution – but in a fresh new way for the 21st century. We want to make a building that is inviting to the public, but dignified, in which the architecture supports the intellectual and cultural mission of the institution.”

Stern’s contextual design is a perfect embodiment of the New Conservation Ethic, for which Steven W. Semes so forcefully argues in his new book, The Future of the Past. Semes makes a convincing case that throughout history, the most successful urban spaces – defined as places people seek out because they make them feel good – are those areas where individual buildings work together to impart a harmonious character to those places. New construction in such places, Semes goes on to argue, should enhance and reinforce the special local character – not detract from it. Stern’s proposed design certainly follows that specification.

Modernist Outcry

Nonetheless, Stern’s desire to be a good urban citizen drew predictable, disparaging reviews from Modernist critics who bemoan the building’s lack of shock and awe. The attacks were best summed up by a headline from the Philadelphia Inquirer: “Let’s make it revolutionary.” The review even goes so far as to bring up that hoary chestnut: The building does not “speak in the language of its time.”

Other critics chimed it with such easily anticipated denunciations as: “It suffers from all the weaknesses of Stern’s neo-traditionalist design philosophy.” “The revolutionary spirit seems to be conspicuously absent in Stern's conservative rehashing of Georgian-style architecture." “This building, with its unsubtle pastiche and imitation materials, does nothing but hold us back.”

Implicit in all the complaints from Modernist critics is their belief that true Architecture (with the capital “A”) should stand in bold opposition to traditional buildings. (However, to make visual affronts more palatable to the public, designers will assert with a straight face that an adversarial new building is “in dialogue” with its neighbors.) These critics are fixated on visual flamboyance without any regard for the making of humane public spaces.

Only critic David Brussat, writing in the Providence Journal, properly understands the building in its broadest context: “But today, the classical revival is as revolutionary as any movement America has seen in recent decades. Bob Stern is among its leaders. His museum design, carried out with RAMSA partners Alexander P. Lamis and Kevin Smith, reflects its spirit. This is what its critics, with their narrow-minded sense of the revolutionary, refuse to acknowledge.”

The commentary on Stern’s design for this new museum underscores how predictably reactionary most architectural criticism is today – and how locked in it is to outmoded Modernist ideology. Whenever a new traditionally influenced design appears – no matter how appropriate – you know in advance what the critics will say. The only unknown is how many times in the scathing reviews the epithet “pastiche” will be hurled.

Clem Labine is the founder of Old-House Journal, Clem Labine’s Traditional Building, and Clem Labine’s Period Homes. His interest in preservation stemmed from his purchase and restoration of an 1883 brownstone in the Park Slope section of Brooklyn, NY.

Labine has received numerous awards, including awards from The Preservation League of New York State, the Arthur Ross Award from Classical America and The Harley J. McKee Award from the Association for Preservation Technology (APT). He has also received awards from such organizations as The National Trust for Historic Preservation, The Victorian Society, New York State Historic Preservation Office, The Brooklyn Brownstone Conference, The Municipal Art Society, and the Historic House Association. He was a founding board member of the Institute of Classical Architecture and served in an active capacity on the board until 2005, when he moved to board emeritus status. A chemical engineer from Yale, Labine held a variety of editorial and marketing positions at McGraw-Hill before leaving in 1972 to pursue his interest in preservation.