Carroll William Westfall

Statues in Urbanism, Part 2: Richmond Fumbles

The war did not end when Grant took Richmond. It dragged on to Appomattox, it reappeared when a huge encampment of veterans installed their Valhalla of Lost Cause heroes on Monument Avenue. It lived on, in candidatures of men like George Corley Wallace, in the Charleston shooting, in the toppling of statues, in the murderous Charlottesville melee a year ago.

Shortly before Charlottesville, Richmond’s Mayor had established a ten-person commission to address the public affront of Monument Avenue. As the capital of the Confederacy it carries a special burden to right the wrong that remains evident in its present. The commission’s report, just released, should have provided a model for other cities, but it falls far short.

Richmond has atoned somewhat in recent years. Since 1996 it has installed statues commemorating prominent local African Americans: Arthur Ashe, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and Maggie Walker. Where slaves were landed for sale it placed a bronze replica of the crate in which Henry “Box” Brown mailed himself to Philadelphia and freedom in 1849. And J.E.B. Stuart Elementary is now Barack Obama Elementary.

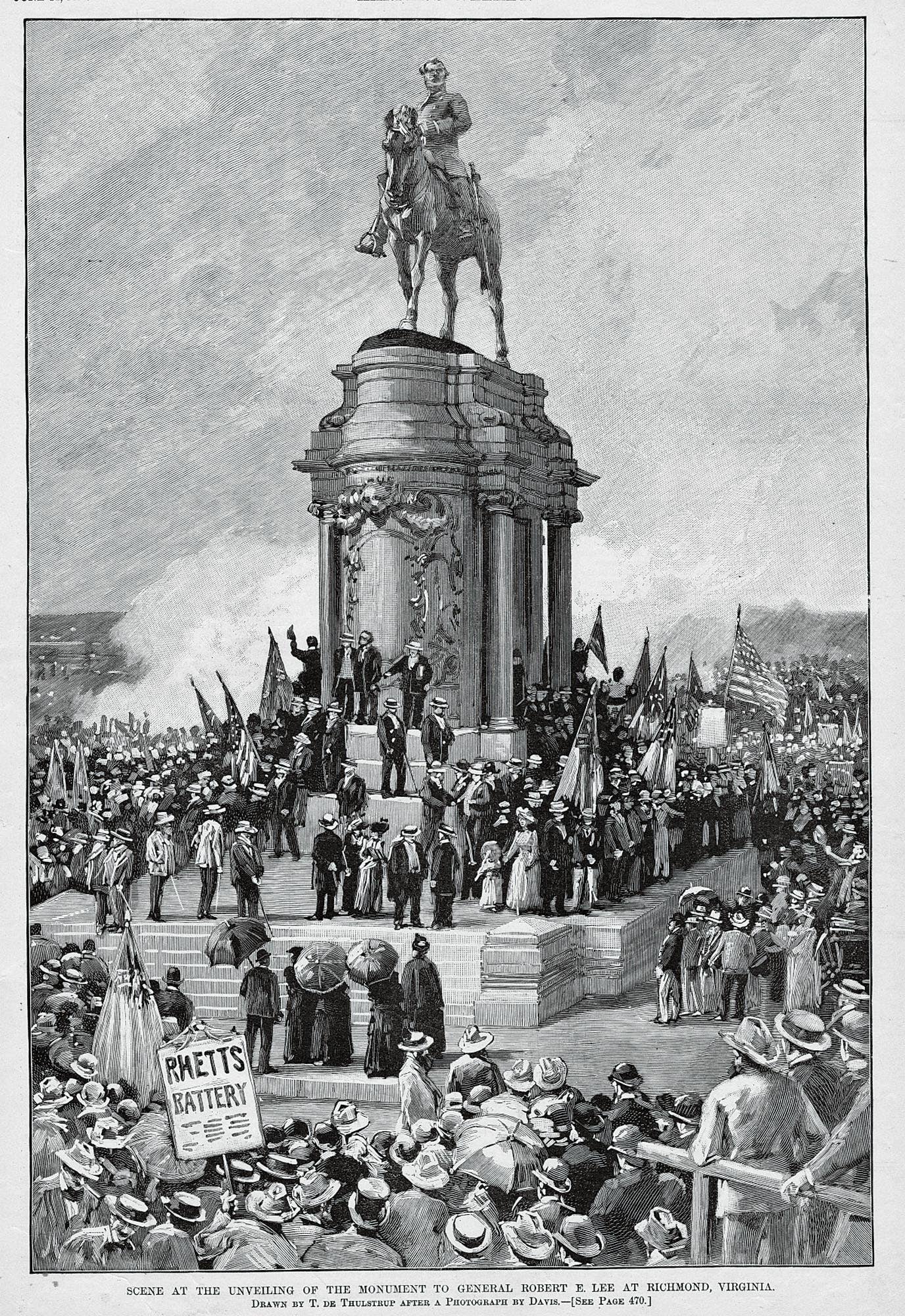

But Monument Avenue remains untouched. Intended as a national rebuke to the war’s victors, it deserves a national response. Laid out in 1887 with a broad, planted median, in 1890 the bronze Robert E. Lee on his horse arrived with others following: in 1907, Jeb Stuart and Jefferson Davis, then Stonewall Jackson in 1919, and finally Matthew Fontaine Maury, 1929, all during the most intense years of Jim Crow.

The commission’s report, acknowledging that Monument Avenue’s narrative can simultaneously be “more cautionary than celebratory, more tragic than triumphal,” offers a few simple actions.

Remove Jeff Davis. The president was a non-Virginian, and his monument’s is the “most unabashedly Lost Cause in its design and sentiment.” Replace it with someone else left unnamed.

Elsewhere on the Avenue add a monument, perhaps one honoring the former slaves fighting as “the United States Colored Troops” in a nearby battle, or perhaps someone else from among those the public recommended.

For the other statues add “signage” and a mobile app presenting new information.

Have the “museum community” prepare permanent and rotating exhibits with more information and context, and have the tourism industry note the city’s “key role in the domestic slave trade” and its “entire monument landscape as an example of its diversity and modernity.”

Finally, the commission wants more art, and by local artists. “All great cities have public art to adorn, teach and reflect its history culture and values over time…Major works of art are an expression of a community’s collective self and de facto represent that community to the larger world.” Public art is “just as important as good schools, libraries, robust economy, sound infrastructure and responsive government.”

That catalogue’s entries are necessary but not sufficient to fulfill the purposes of the city or the nation, and more is needed than a purge, signage presenting more and better information, an additional monument or two, and some “new contemporary works” of art by local artists. That is not enough to countermand the cause those bronzed individuals served, the purpose of those who installed them, and the desires of people who would perpetuate injustice.

Monument Avenue’s statues and those elsewhere stir people’s passions because what they express is embedded in a familiar tradition that allows comparison between the past and their hopes for the future. Some want no more men on horses while others want to preserve injustice and roll back equality. The statues and the setting stand for the legacy of Jim Crow that left people bottled up within the city limits while the suburbs and its tax revenue expanded and their city was left to molder.

For redress, the commission wants more statues from Richmond’s “arts community.” That community values creativity conquering the anathema of tradition. It revels in its latest acquisitions, the 2010 addition to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and Steven Holl’s brand new Museum of Contemporary Art. Highly visible in public but hardly public art, these personal expressions, latest cutting edge, “of their time!” and intentionally rebuke Richmond’s traditional buildings from Jefferson’s Capitol forward.

The commission fails to understand that good public art—statues, buildings, urbanism—belongs to a tradition that people can relate to. It seeks beauty as the counterpart to justice, and like justice, beauty is based on principles that are congruent with human reason that endure across time within a tradition that absorbs the innovations that address ever changing circumstances.

Needed here is the very best that tradition now offers. Fight the fire of Monument Avenue’s “celebratory” injustice with more and better fire. Here and in other cities add new monuments that move the ensemble into the present with works whose pedigree in tradition and quest for beauty, the counterpart to justice, give the lie to past and present injustice.

And furthermore, address the many injustices in the metro region’s urbanism so that it may fulfill the hope that these urban amendments to the city kindle in the enlarged “community’s collective self.”

Carroll William Westfall is Emeritus Professor, School of Architecture, University of Notre Dame. He can be reached at westfall.2@nd.edu. This Forum is a follow-up to his Statues in Urbanism published in the October 2017 issue of Traditional Building.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.