Carroll William Westfall

Celebrating Where the Public and Private Meet

Traditional architecture has always served both our public and private lives by paying attention to the intersection between the public and the private realms that we inhabit.

When the role of tradition is overlooked, a building’s contribution to the common good and the public realm is neglected, and it becomes nothing more than an art object. This outcome can be attributed to what in 2010 Tom Schumacher identified as one of Modernism’s “most persistent doctrines”: the outside is the result of the inside.

Letting the function inside dictate the building’s three-dimensional configuration or dressing it with a façade produces what Robert Venturi, in his remarkable 1966 book Complexity and Contraction called a duck or a decorated shed. In both cases, the building becomes a private thing that presents itself as more important for what is inside than for the contribution it makes to the urban setting it occupies.

The result is a lack of civility that becomes more extreme in one of the most common kinds of large building being built today, the glass-enshrouded the -through or see-into glass-enclosed frame. These are the inevitable result of carrying modern materials and technologies to their extreme efficiency in construction, although not in sustainability and civility. They fail to produce a façade as anything more than a membrane between inside and outside. Such buildings fail to pay tribute for the grace of being allowed their presence in the public realm. They undermine civility by failing to provide backdrops for the public life. They serve only the selfish interest of the building’s owner.

The biggest offenders now are of course the soaring towers whose proliferation have forced into the background their predecessors that used tradition’s forms for tall buildings to serve and express their roles in supporting the public life that nourished the civic good. The threat that mere commerce posed to that good was recognized as commerce was first gaining a foothold in daily life. In a favorite building among Modernists it was celebrated in Sir Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, built in 1851 to house the first International Exposition, but only as a temporary exhibition in the city.

It was held in a vast glass-enclosed shed that from the outside revealed what was inside, how it was arranged, and how the visitor would move through, which cleverly anticipated the ducks, decorated sheds, and see-throughs that followed. The exposition’s sponsors required that after the five-month and two-week run it had to be removed and the park it occupied restored to its original condition. Paxton drew on his experience in building greenhouses to build it in a mere eight months with cast iron parts for a frame enclosed with glass. After being disassembled a larger version was built in a different London park.

It raises the same question as its glass enclosed successors: does such a building have a visible façade? In daytime sky glare dematerializes what I see, and at night interior lights display what’s inside. When the glass is held by a cast masonry frame or a metal frame with spandrels perhaps it has a façade, but the glass still dominates.

There is another, but rare, way to make a conspicuous building that lacks a façade. Bertram Goldberg managed that feat in his 1959 Marina City on the Chicago River’s north bank. Its pair of concrete towers begin with eighteen stories forming continuous parking ramps, a bare midriff, and then forty stories of ripples made of half-circular balconies. None of this addresses the public realm.

The towers, like their see-through counterparts, also deign to sit on the same earth that their users tread. Instead, they rise on stilts above a marina on one side and free of the ground on the other, giving access to the interior only through elevator lobbies. This now-common extreme denial to the public realm’s importance is lauded in another, exemplary icon of Chicago architecture, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s vaunted post office and federal court house and office building. They stand aloof from an area larger than a city block that hosts nothing more than Alexander Calder’s orange “Flamingo.”

Traditional architecture always offered a façade for the public realm and as an interface with the interior it included a lobby or vestibule. A building on stilts with a glass-enclosed ground floor offers neither, and this kills public activity around it. The liveliest public places in cities are where retail establishments entice people inside, as the Crystal Palace did, by using shop windows to display what is available inside, and they normally substitute an air lock for a lobby lest a lobby slow direct access to the goods.

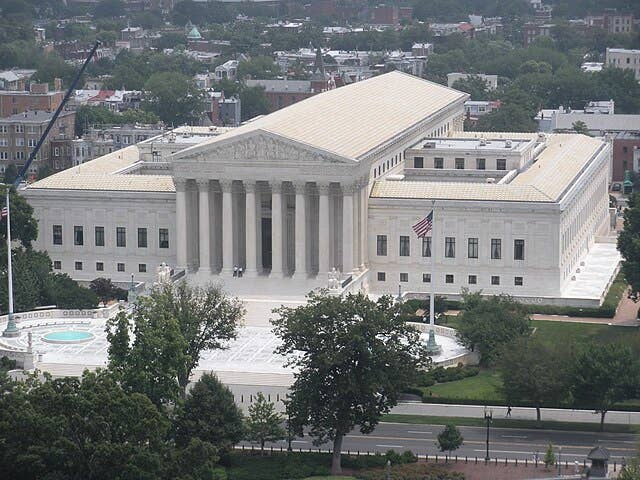

Vestibules provide a valuable separation between the hurly-burly of the public realm’s activities and interiors where privacy and more decorous behavior is called for. In a residence a foyer or mudroom serves, and in buildings such as theaters, libraries, churches, or courthouses something more is called for. In a proper interior a person moves through a sequence that arouses expectations and prepares for what will transpire, a transition equally important when exiting.

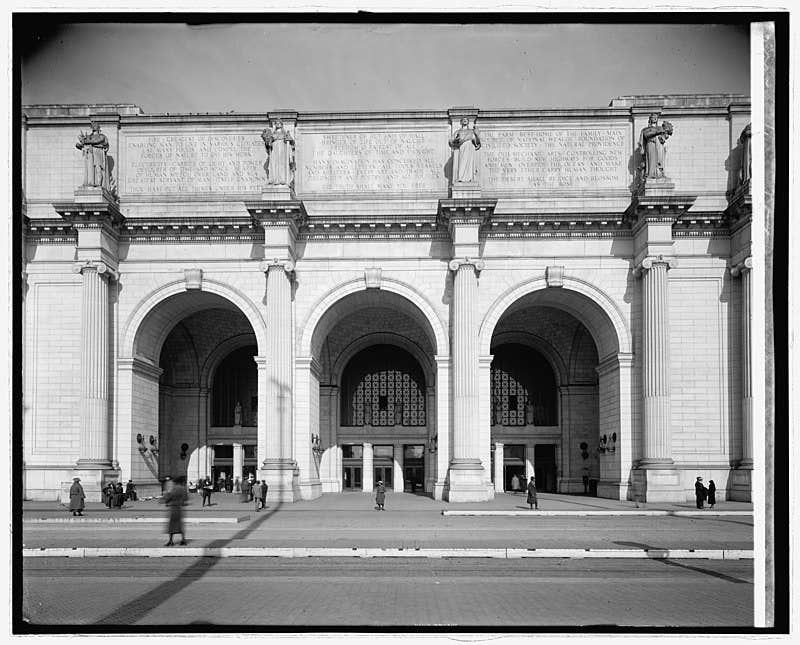

Vestibules can render valuable service to cities. Our urbanism is shamed by the arrival offered those traveling by automobile; they encounter suburbs, strip malls, and traffic snarls. Visitors arriving by air hardly fare better. They are offered quick and easy transfer to ground travel through facilities that are architecturally akin to sports arenas. Those fortunate enough to arrive by rail are greeted and fêted when the city’s great vestibule is a traditional railroad station. The present disgraceful Grand Central Station ought to be replaced by its predecessor so that people could arrive with the thrill available again at Daniel Burnham’s Union Station in Washington D.C. built between 1902 and 1908.

Off the train and up from the platform you arrive in the concourse. Proceed out through paired columns beneath each of the five great arches and into the cavernous vaulted waiting room with colonnades on the right and left offering entry into sky lit, vaulted halls, one originally for ticketing, the other for food. Across the hall the great arches on the concourse side are replicated with the three central ones open to the outside. Beyond them the Capitol’s great swelling dome becomes visible. Entering the façade’s depth you see handkerchief domed arcades stretching out left and right. Moving out into the forecourt plaza it is worth looking back to the façade where the arches receive columns and an attic to produce a triumphal arch. In the plaza three pairs of rostral columns carrying nothing except gilded eagles stand away from a central fountain whose opposite side has a statue of Columbia looking toward the Capitol.

Even equipped as it now is with a wide range of food and shopping outlets for its constant stream of traffic, Union Station remains an impressive vestibule worthy of a nation’s capital. It offers a lesson that the descendants of the Crystal Palace and the two look-at-me exercises in Chicago cannot: A city is a place that serves and expresses the reciprocity between private concerns of individuals and the general, public, common good. Traditional architecture gives this public realm a public face, while buildings that neglect this traditional and necessary role turn out to be the mere personal fancies of the few.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.