Carroll William Westfall

Progressivism and Progress

.This month 90 years ago an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art introduced Modernism to Americans. In seven weeks, 33,000 people saw photos, drawings, and models of several European and a few American works, and a version then toured eleven America cities. The catalogue essay by its curators, Henry Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson, has had a long lasting and unfortunate effect on architecture in America and throughout the world.

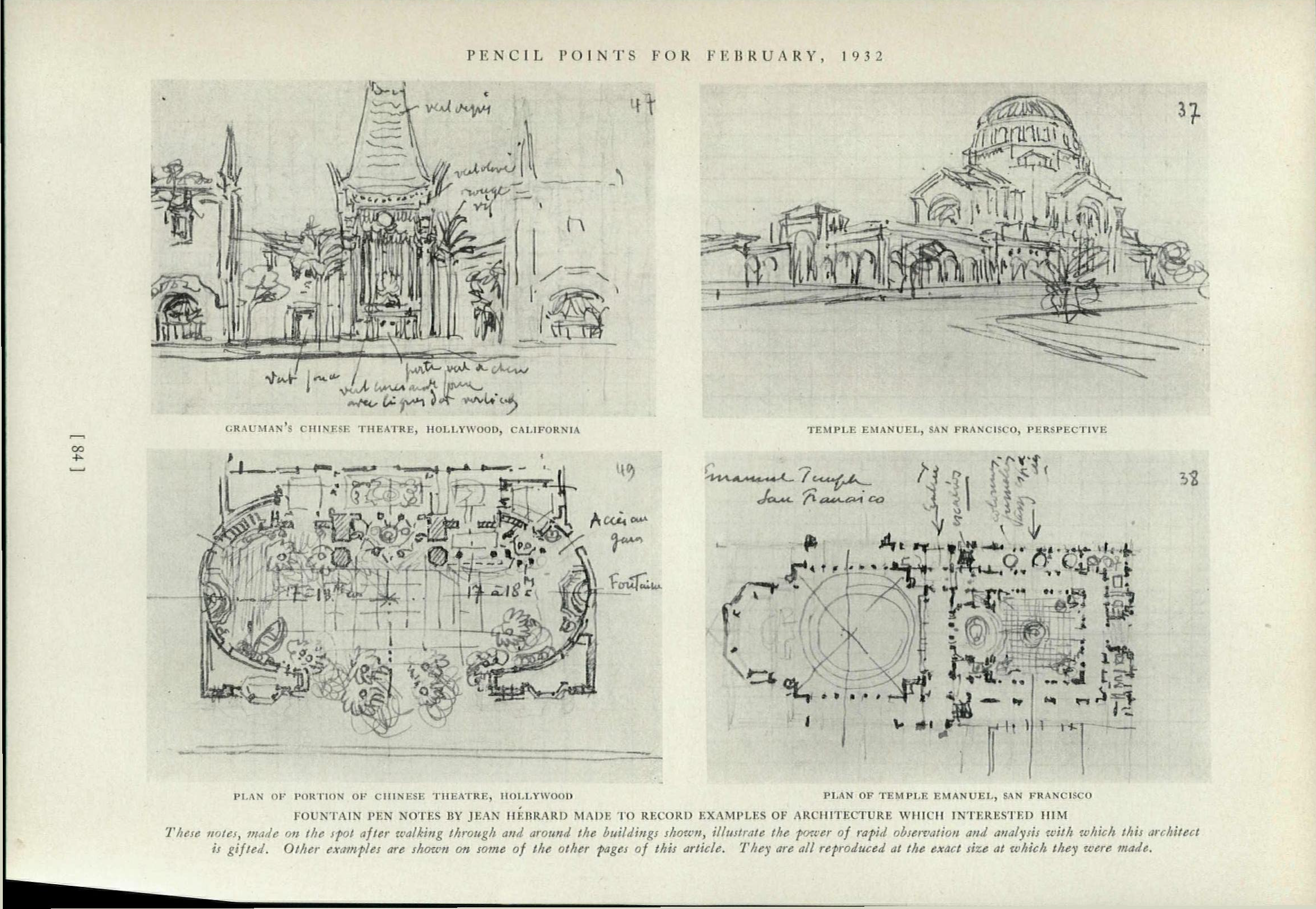

Fifty years after the exhibition closed, with Modernism firmly rooted in America, Richard Guy Wilson contributed an important overview in a celebratory issue of Progressive Architecture. Formerly known as Pencil Points: An Illustrated Monthly JOURNAL for the DRAFTING ROOM, it featured traditional work, used drawings and texts to teach, and included drawings of construction details with advertisements relegated to their own section. Its February 1932 issue featured an article and sketches by sketch by Ernest Hébrard. Among its short notices section was the MoMA exhibition running from February 10 through March 23.

Traditional designs gradually faded from the journal, and in 1945 Progressive Architecture was added to the original title, soon becoming its exclusive title. That year’s February issue, devoted to houses, noted that now “more architects than ever are prepared to lay aside their copybooks and to design … with reference only to the problem itself” to achieve a “real and honest architecture” exemplifying “the progressive attitude toward design we like to encourage.” Its editorial copy was interlarded with advertisements for materials and manufactured products that were gaining importance in the post war era.

By the exhibition’s 50th anniversary the “progressive attitude” had reached a future far removed from the Depression, the Second World War, and the nostalgic regard for emblems of the past such as Colonial Williamsburg, which Wilson noted had opened in the same year as the exhibition.

The exhibition’s catalogue essay became required reading legitimizing the Modernist architecture that was achieving worldwide prominence. In an article titled “The International Style Twenty Years After” and then appended to the book’s 1966 edition, Hitchcock suggested that the term “International Style” was out of date and better forgotten. “The ‘traditional architecture,’ which still bulked so large in 1932, is all but dead by now. The living architecture of the twentieth century may well be called merely ‘modern’.”

This change has been hailed as a welcome and beneficial revolution in architecture. Several architects featured in the exhibition had offered the new architecture as a vehicle to serve and to hurry into existence a revolutionary, new civil order. Le Corbusier’s 1927 Toward an Architecture had closed with the ringing call,

Other architects, they declared, “have buried architecture… from a thwarted desire to continue the past,” or they addressed only function or structure while neglecting the necessity of its aesthetic content in their “over-anxiety to modify and hurry on the future.…We have an architecture still.”

That “aesthetic content,” that is, the formal appearance that identified the building’s style, covers the word that every architect now learns and uses to identify a building. Style is a hard worker. It unites buildings that look alike and separates them from other groupings. The buildings of the Egyptians, the Chinese, the Greeks, and “our ancestors in the Middle Ages” had a style, and now, so do we. Like every style, it is the product of the era’s cultural influences with the building being a distinctive expression of the era’s culture and the architect serving as an automaton responding to those influences or a starchitect who channels them.

The essay stressed the aesthetic basis of style over function and structure, two conditions that were given influential roles and that an International Style building was assumed to satisfy (even when it did not). In our modern era starchitects change the styles that influence others, and they have been doing so at a rapidly increasing rate. Critics and historians, or the architects themselves, usefully explain how these express the will of the era and condone this role for architecture as an art of creative personal expression.

The role style is given is a major flaw in the essay and in current practice, a flaw matched by stressing internationalism. Together, they exhibit Modernist architecture’s failure to understand the essential nature of a building and of architecture.

A building is necessarily a public object. It necessarily occupies land, and land is ultimately under the control of a public body: ergo, like every individual in that body, it carries the responsibility to serve and defend the common good whose ideals are peace, justice, and abundance. Inserting laws and buildings into that sentence will reveal the central kernel of their role in fulfilling those ideals: every law and building carries the responsibility to serve and defend the ideals of the common good.

Buildings are built by the institutions that are organized to form the nation. They range in size from families to the national governments that exercise ultimate authority in defending h eland and assuring that it is occupied in ways that serve the common good. It either builds on the land itself or licenses others to do so, and these buildings constitute the architecture of the nation’s urban and rural districts. These buildings can be as varied as their counterparts, the laws of the land, and like them, they serve the ideals of the common good. It is fallacious to limit a building’s service to offering a style that places it within an international frame of reference. They serve as nation’s common good, and a nation’s governmental authority does not extend beyond its boundaries except through its willing participation in international organizations and pacts.

The nation’s own traditions made legible in it architecture confirms and reinforces tradition’s role in the security of the nation’s civil life, and it has done this for as long as there had been the art of building. This role is necessarily superior to claims that architecture is primarily an art of private, creative, original artistic expression.

Today’s Modernist arts were launched as revolutions, and they remain as valued as revolutions. Revolutions offer progressive change by using visions hatched in the present to distance the present from the past. As an adjective, progressive differs substantially from progress, a noun that points to improvements in human flourishing made through innovative reforms within a tradition.

Today’s progressive Modernism germinated during the commercial and industrial revolution and bore the fruits of the International Style in the wake of war and political revolutions on the Continent. Meanwhile, in Britain’s American colonies, in the 1770s reforms were initiated within the traditions of classical law formed by Britain. In 1776 the reforms reached the understanding of human nature and defined certain “self-evident” truths, “that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” Using reason and experience, they enshrined those truths in a constitutional democracy that subsequent reforms have amended and that now reverberate across the globe. Here church and state are separated and the natural rights of individuals, their freedom of speech and right to petition and elect officials and so on are safeguards in a “government of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

This is progress that has been made within the classical tradition since its beginnings in Athens and Jerusalem. Its nature is to build urban and rural realms buildings make clear their contribution to the common good. Their character, derived from their configurations and membratures, exhibit the interchange of tradition and innovation that comes from respect for what they inherit, knowledge of the art of building, and innovations offered by the present to serve the future. Each one always makes clear the role it plays, whether capitol, courthouse, school, bank, or filling station.

Modernist buildings offer no such beneficial service. Its poster children are by irresponsible patrons seeking unquenchable satiation and their vainglorious, narcissistic architects who together display disregard access to abundance by the many. Other sponsors are government agencies seeking efficiency, people in higher education wanting to show that they are “with it,” and the great mass of those involved in building who want economic efficiency at the cost of longevity.

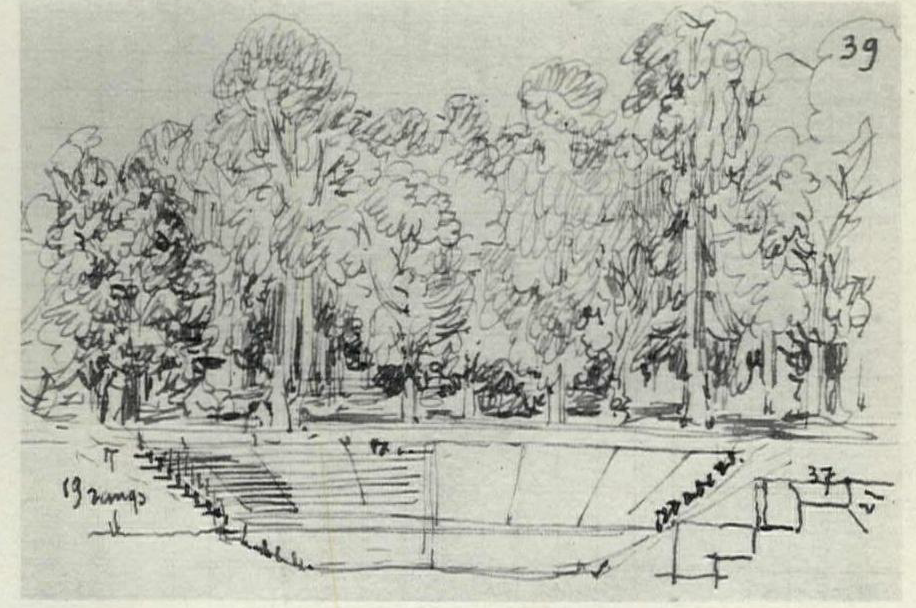

In Modernism, the past is past and the future is not our concern. No magazine serving Modernism would include a loving drawing of a 30 year old building as Pencil Points did Hebrard’s Hearst Greek Theater nestled among Berkeley’s eucalyptus trees, the first of John Galen Howard’s many buildings on the Berkeley campus in a time long gone. Progress has been the way of the classical tradition, and now it is gaining momentum with reforms that illustrate how beautiful buildings can serve America’s ideals.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.