Carroll William Westfall

Odd-Man-Out?

Traditional architecture is increasingly eroding Modernism’s dominance with some encouraging signs going back several decades. In 1972 Clem Labine embraced preservation and in 1988 founded Traditional Building Magazine. A year later Thomas Gordon Smith became architecture chairman at the University of Notre Dame and instituted its vigorous curriculum in classical and traditional architecture. Since 2003 Notre Dame has administered the Driehaus Prize, a counterpart to the Pritzker Prize, to honor modern traditional and classical architecture. And traditional and classical instruction has found a niche presence in other schools and a presence in the portfolios of many professional offices. Still, the professional and popular media boost Modernism and ignore the movement.

Now Hydra-headed, Modernism is the emblem of internationalism, peace, and prosperity. After defeating ultra-nationalist Nazi and Fascist regimes, the victorious coalition founded internationalism’s fountainhead, the United Nations, which had an international group of architects design its New York headquarters building. Its Modernist style featured the materials and technology that had won the war. Now it broadcast this Modernist image of a new world order as it repaired the war’s devastation.

Philip Johnson, an antisemite who had attempted to install National Socialism in this country, played a major role in promoting Modernist architecture. In 1932 with the art historian Henry Russell Hitchcock he had imported and promoted it through a book and exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art titled “The International Style.” After the war he achieved fame as a taste-maker promoting its avant-garde styles.

Modernism soon achieved default status globally, bringing with it the near total dissolution of the traditions used in the art of building in local and national communities when building grand and humble religious, civil, commercial, and residential buildings and urbanism. Their villages, towns, and cities had been as diverse as the communities living in them, giving them pride, connecting their present with their past, and promising continuity into future generations.

But under Modernism urban areas throughout the world now look as much alike as the automobiles clogging their streets. This has made many untouched morsels of earlier eras quite precious, with two important rebukes to Modernism.

One is historic preservation. Virginia in 1895 had this country’s first state-wide program; now they are ubiquitous. In 1949 came the National Trust, a membership organization, and a federal program in 1966. None of them can override property rights to preserve older buildings and places; most simply document them and foster work to stay the wreckers’ hands.

The other is mass tourism, but it tends to imperil what preservation seeks to protect. Prosperity and jet travel now make distant destinations an easy reach for hordes of Americans, Europeans, Asians, and others eager to experience the humane architecture and urbanism of earlier eras and now absent in their Modernist homelands. They encounter outstanding ageless grand buildings and vernacular urbanism while their numbers cause physical and sanitary deterioration. Consider Venice: one of Europe’s larger cities in 1775 with 170,000 residents, today a mere 51,000 live in its historic center’s islands hosting 5.5 million yearly visitors with displaced Venetians commuting in from the mainland after having converted their residences into tourists’ lodgings. The city’s fragile fabric was so damaged by cruise ships they are now forbidden entry, while Venice, like other cities, is considering imposing an entry fee to cover tourism’s costs. Other popular destinations are similarly swamped: Florence (16 M), tiny Cinque Terre (2.5 M), Prague (8 M), Amsterdam (5.43 M), Dubrovnik (1.5 M), Rome’s Colosseum (10 M), and the Eiffel Tower (nearly 6 M).

American cities such as Charleston, Savannah, and Saint Augustine also attract tourists. A resuscitated Williamsburg has been made tourists-friendly, and Washington, D.C. is on everyone’s bucket list. Perhaps only Chicago and New York have Modernist buildings and urban fabric attracting tourist, but zoos, museums, views (San Franisco), sports venues, adventure parks, and other things are more common magnets.

Another rebuke to Modernism is the increasing role for new traditional architecture and urbanism, a stronger movement in Europe than here. Important examples are war-damaged sources of national pride.

Warsaw’s Old Town Market Square was rebuilt in 1948-53 “as it was where it was” in the 17th and 18th centuries. In Germany with reunification after the 1989 removal of the Wall Dresden’s Lutheran Frauenkirche by George Bähr, 1726-43 was rebuilt, 1994-2005.

In 1933 Hitler had made Paul Wallot’s 1884-94 Reichstag Building unusable; it was restored and redesigned in 1995-99 by Norman Foster. Nearby, the East German regime had cleared the ruined Royal Place (Andreas Schlülter, 1702ff) to produce the Marx-Engels-Platz, then filled it with a loathsome parliament building (1973-76), and that was razed and replaced with the Humboldt Forum (2013-20) holding museums and other cultural facilities. Built on its original footprint to enable a future installation of original interiors, three of its facades reproduce the originals and thereby restore continuity with museums by Schinkel and others, leaving the lesser fourth one for a later reconstruction.

America’s equivalent national monuments survive intact (but not Penn Station), but Modernism prevails for new, major government, institutional, or commercial buildings, although there are instructive chinks in Modernism’s carapace. A decades-long program completed within the state’s budget constraints and procedures has produced a new campus for the recently established public Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia that Glavé and Holmes modeled on Jefferson’s University of Virginia. At Notre Dame, John Simpson’s 2018 Walsh Family Hall for the school of architecture exemplifies modern traditional and classical architecture.

RAMSA embed a residence hall with Yale’s pedigree at Yale. But McKim, Mead, and Whites’ Columbia has scarred Morningside Heights and continued using best-of-its-year Modernism for its new uptown campus. Especially egregious is the federal govenrment, defacing our capital and other cities here and abroad with the latest ultra-Modernist fashions. Giving the lie to the explanation that federal govenrment constraints cannot be abridged for something not Modernist is the 2012 impressively classical Federal Building and Courthouse in Tuscaloosa, Alabama by HBRA.

For lesser buildings this country can show a better response to preferences for national and regional architectures. This may be a reaction to the ubiquitous homogenizing of international globalism, or more likely a market response to what people prefer. Polling reveals that people prefer new traditional or classical buildings over Modernism by margins of two to one, three to one, and four to one.

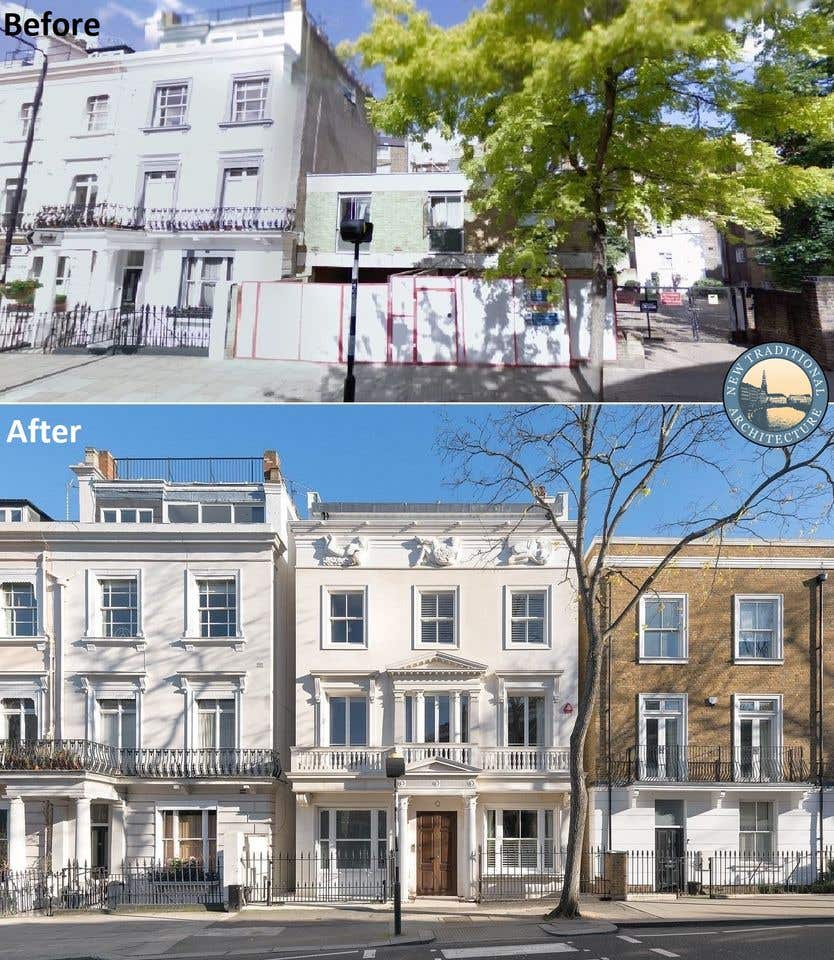

Tradition’s rise is evident on Facebook postings here and abroad, for example by New Traditional Architecture and Architectural Uprising launched in Norway in 2014 and now with 6.2K followers.

Examples here include retrofits of Modernism and newly built fabric sporting ages-old public exteriors and modern private interiors. Our country’s builders have always favored regional traditions for work they offer for sale to homebuyers but investors building rental properties churn out a dispiriting Modernist vernacular. If architects are involved they learned to scorn tradition as they design with computers.

Admirable examples of modern American traditionalism are available for instruction. Seaside, Florida by Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk was built way back in 1978-1985, and the New Urbanism movement that followed is seen in the work of Dover, Kohl & Partners and many other architects swelling their portfolios with higher-end examples.

When buyers control the money the market gets it right, but those who spend other people’s money fall for Modernism as the style necessary to serve our forward looking, free, progressive, and economically prosperous nation. Their canards reject the alternative of traditional and classical buildings: they serve totalitarian authoritarianism, they cost too much to build, the people who can build them are no longer available, and so on, all disproven by new construction. Anything not Modernist to an immoral betrayal of American ideals. Proof? Nazi and Fascist dictators used it: ergo, case closed.

But this is doubly faulty.

First, buildings are built to serve and express purposes that ultimately contribute to the common good and express the authority of individuals and governments in serving and protecting those purposes.

And second, Modernism reduces architecture to a style expressing an architect’s creativity, the will of the epoch, and the latest fashion sponsored by partisans of particular political positions.

But architecture promotes unity while styles promote division. Americans take pride in their non-Modernist, traditional and classical American buildings, buildings that partisans label classical and therefore authoritarian and backward looking and forbidden for current use. For the people in general (but few in the culture of architecture) they are emblems of American traditions, servants in the political life, with few seeing them as styles that stimulate partisan differences. Partisan contests are certainly the stuff of politics, but politics in the hands, heads, and hearts of people of good will overcomes partisanship to find policies that serve the common good. A uniquely American tradition in architecture has served revered policies in our past, and it stands ready once again to offer beauty as a complement to justice.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.