Carroll William Westfall

Observations from Sicily

I have lived in Rome for longer and shorter periods for more than 50 years. I have spent time in other Italian cities, and they confirm the comment of a Roman bus driver as he inched through Naples: it is “un altro paese.” Every Italian city is, actually, although Naples and Sicily have many similarities because they have similar histories, especially recently when for several centuries they were bound together in the of the Spanish-ruled Kingdom of Two Sicilies. Here are six observations I carried away from my recent tour in the ball that the boot of Italy is always ready to kick.

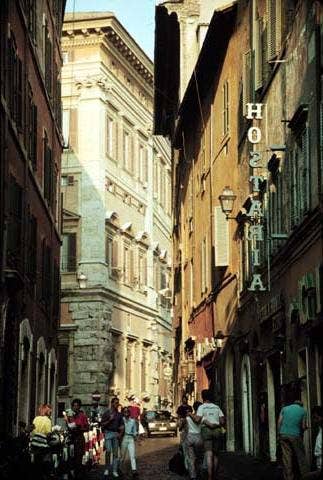

1. As elsewhere in Italy, most Sicilian streets are narrow and some are wide, some crowded and others not, all are worth following, and each one is distinctive in different ways in different regions.

Consider balconies: they are absent in Rome, sporting in Venice, and especially conspicuous in Naples and Sicily enriching the profile of both narrow and wide streets. They are often messy as in Naples, but especially attractive when considerable control was exercised as it was when Noto was rebuilt on a new site after an earthquake destroyed the old town in 1693.

2. In Rome an important palace is often made to look important by realigning the street to produce an impressive corner view, as Joe Conners showed.

Balconies perform this service in Sicily, at least in Noto. The major street’s balconies are neat and trim but at a major palace on a side street they project farther, are larger, and are extensively enriched with sculptural decoration.

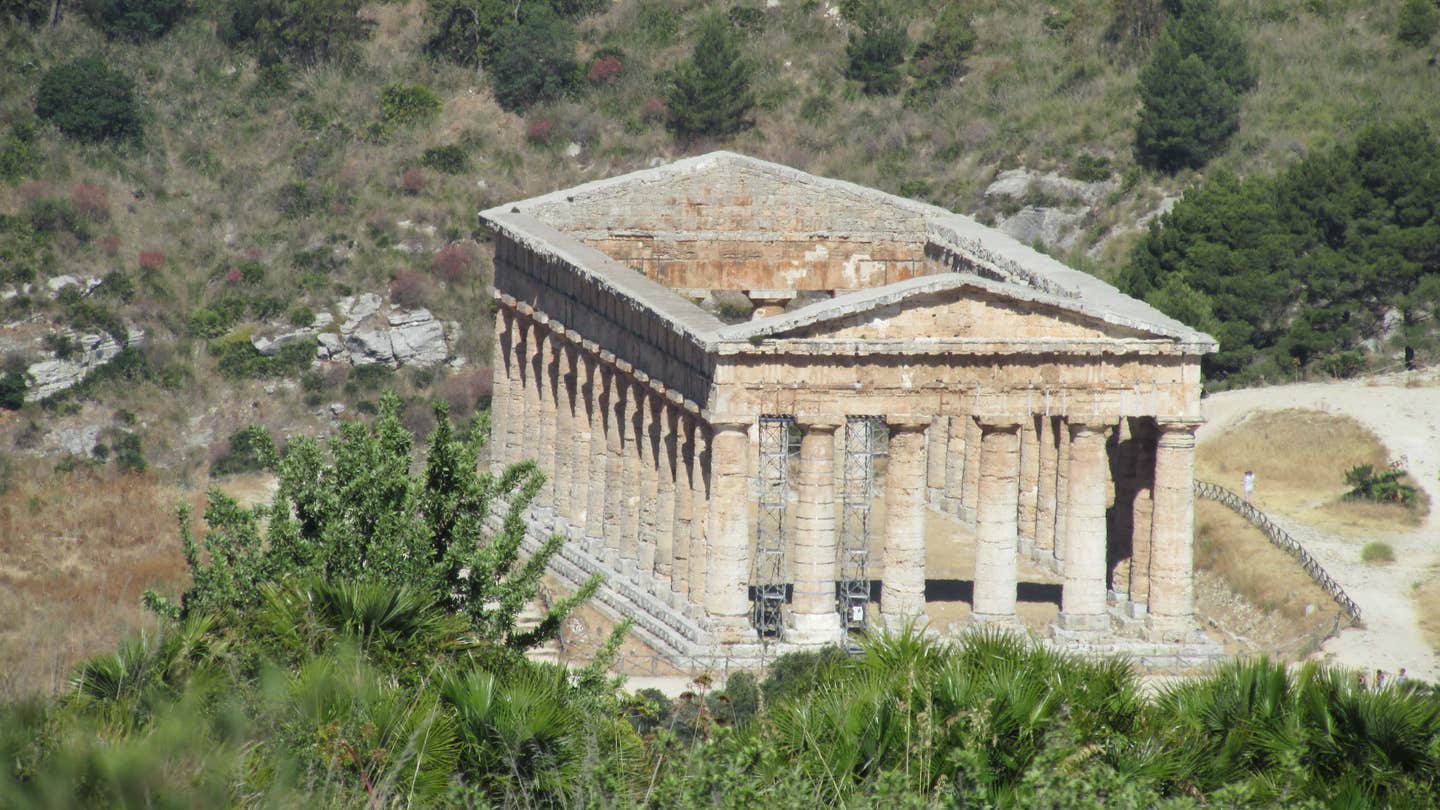

3. Sicily abounds with buildings dating back to when it was Magna Grecia. The temples seem to occupy the urbanism much as their cousins in Athens do, although the evidence depends on largely unexcavated sites.

In Athens the Parthenon is first seen from the Propylaea presenting an oblique corner to this favored viewing position. Norris Kelly Smith noted that this reveals the temple in one quick glance and invites a person to know it more completely by exploring it over time and from many positions. It can in this way stand for the Greek city whose population was limited (and hence its casting off colonies) to the number of citizens who could be viewed in a single assembly (the ecclesia) with the character of the individual members known over time through intercourse with them in daily life.

And so too in Sicily. In Segesta the temple that was left incomplete is seen in this way at a distance from the central area with its theater and on its own slight rise or acropolis. The temples in Agrigento are strung along a slightly elevated ridge and not in a line, each a bit elevated and each offering an oblique view to the path now connecting them, which we may assume follows an ancient path.

4. This way of having a temple viewed contrasts with the ancient Roman practice of facing them frontally. This frontality is reinforced with podium-framed steps and its situation at the short end of a long precinct entered at the opposite end. When we see one in a diagonal view it looks awkward.

Renaissance urbanism also used frontality, which allows the building to exercise a similar authority over the viewer. Note what occurs when returning to Rome from the Vatican by crossing the Ponte Sant’Angelo. You confront an important but not imposing secular building that receives your attention and then directs you to choose which of two oblique streets you will follow.

5. The Baroque sought spatial excitement. At Saint Peter’s Bernini would have manipulated frontality to achieve Baroque drama. He intended to prevent a direct view of the Basilica until passing though or around a “third arm” (not built) of his great colonnade with the visitor confronting the Basilica basically frontally and thereby demanding recognition of the Church’s authority.

Carlo Maderno had introduced a different, and more usual, Baroque spatial experience at Santa Susanna in Rome. Quickly picked up elsewhere, it offered a spatially expansive, shadow-saturated experience with the building to gain attention from the flanks. Sicilians greatly expanded this aspect of the Baroque as they invite you to move around and look up for your full experience.

In Syracuse, the Duomo’s façade dominates and energizes the piazza with its several layers and multiple stories of columns and other accoutrements. In post-1693 Noto several buildings or their parts offer enticing views from diverse angles in piazzas and streets. And note: these buildings look quite different at different times of the day and year as the sun’s light produces different highlights, shades and shadows.

6. The examples so far span millennia and show variations within a guiding Italian tradition that was constantly adjusted with innovations to account for changing times, regional and local circumstances, and artistic personalities. Throughout Italy the buildings in different cities are unquestionably Italian while also being distinctively Sicilian, Roman or Florentine, each place “un altro paese” relative to one another but nonetheless all in the same paese.

But when, with the rest of the world, embraced modernism it retained superficial qualities of local traditions but lost the hold on urbanism. The newly built apartment buildings beyond the centro storico are often given a familiar color and, in Sicily, equipped with balconies, but individually they seem to swim in a void, adrift and unmoored to their neighbors, and when they are docked among others they lack the connective tissue of urbanism.

Sicily, then, has its own unique traditions that can be adapted to enrich urban settings elsewhere, and it reminds us of the importance of knowing and honoring local, regional and national traditions more than merely superficially. And as elsewhere, it also presents a stark lesson in what is lost when traditions are discarded.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.