David Brussat

New Blog, Old Conversation

Conversation about architecture, known as “the discourse,” has continued for centuries, even millennia. Today a new thread in the discourse, if I may be so bold as to call it that, is initiated with this blog. “Architecture Old and New” is hosted by the websites of Traditional Building and Period Homes, a pair of trade journals published by the Home Group of Active Interest Media – to whom I am grateful for the platform and hopeful of pleasing the 10 million readers who visit the websites annually.

As the author of this new blog I benefit from the experience of my old blog, “Architecture Here and There,” which continues. It started in 2009 as an offshoot of my job as an editorial writer and architecture critic at The Providence Journal. There I worked for 30 years, writing for the last 25 years a weekly column on architecture. Today the blog is independent, speaking for traditional architecture and its allied arts and crafts, and against the modernist design establishment, no holds barred. This new blog is dedicated to the same principles but directed specifically at the makers, buyers and sellers of work grounded in those principles.

I do not know how you all came to choose tradition as the basis of your work, but I suspect that most of you feel that your choice arose from an approach to design that was more natural than its alternative.

The discourse of this blog springs from its author's belief that all humans experience architecture more intimately than other arts. From near birth we all experience houses and other buildings hour by hour, day after day, as long as we live. Except for those whose design educations have blunted their natural instincts, people have an intuitive grasp of what's important about buildings and their appearance. While traditional architecture has evolved over centuries of trial and error, handing down best practices from generation to generation, the business model of modern architecture officially rejects precedent, which restricts practice to a limited variety of forms that almost always conflict with their setting and tend to alienate the public. As a result, most people have a strong natural preference for traditional buildings, arts and crafts.

Churchill said, “We shape our buildings and they shape us.” In fact, a few of us shape the buildings that shape the rest of us, and the conversation between those few and the rest of us, well, it tends to flag. The few are not listening.

The Duality of the Discourse

Most modern architects have been taught to treat the public's dislike for their work as a feather in their cap. The free market helps practitioners in other fields bend their efforts toward the satisfaction of public desires. Not architecture! Most major commissions for buildings are handed out by committees – panels of design apparatchiks who follow the party line of the architectural establishment. Only in single-family residences does traditional design still dominate the market – because most families still choose their own home.

So the discourse – the conversation about architecture among architects – is really a pair of discourses. The modernists, secure in their control of the establishment, have little to discuss: They do their work as they learned in school, establishment journals applaud, prize juries reward, and schools pump out more young architects trained to continue ignoring both their clients’ needs and their critics’ protests.

Since modern architecture claims to value innovation above all, firms have little incentive to share design ideas. Modernist conversations focus less on design and more on how the industry can address challenges of climate change, inequities of race and gender in hiring and promotion, the widely perceived inadequacy of the word “intern,” the industry’s interests in Washington, the heavy college debt load of architecture graduates, and other issues more important than the theory and practice of placemaking – including how to prevent the idea of “beauty” from rearing its ugly head.

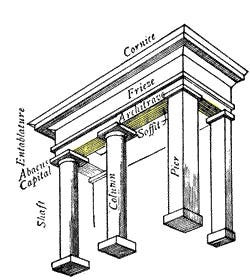

The discourse among classical and traditional architects proceeds almost entirely apart from the discourse among modernists. To judge by my long experience as a member of the TradArch listserv (operated by Dr. Richard John from the University of Miami School of Architecture), the discourse of classical and traditional architects features two distinct arenas: 1) how classical and traditional work can recapture a share of the industry lost to modernism since 1950, and 2) how many soffits can dance on the head of a pin.

Excuse my chuckling at the technical discussion of architectural detail that animates so much of TradArch. A heated debate over some aspect of soffits was under way when I first joined the list. I did not even know what a soffit was. (It is the ledge under a cornice or the overhang of a roof.) But architects seeking advice from fellow practitioners on practical questions of design and construction is probably why TradArch is so valuable to most of its members, be they threadomaniacs or lurkers who read but are rarely heard in the discourse. The latter are of vital importance because they, too, transmit discourse into practice.

Debate or Battle

Since I’m not an architect, the question of how to give the boot to the Mods is my main concern. Andrés Duany, who is writing a treatise called Heterodoxia Architectonica, wants to broaden the definition of classical to include Louis Sullivan, other wayward classicists of the 19th century, and even some downright modernists. Capture territory, he cries – but the treatise (whose Book I was edited in part by me) is not yet published and so its impact remains to be seen – except on TradArch and other forums, where the “battle” is joined, its influence is felt, and its bearing on the discourse is often quite entertainingly termagant in tone.

Debates over terminology – whether the word “classical” is too backward-looking, or whether the word “modernist” is designed to take over the future – are entertaining to wordsmiths, but nomenclature will not be the silver bullet. Equally unlikely is the vision of a traditional beachhead in architecture schools. Architectural education will change only when the market for architecture changes. More demand for traditional buildings will create more demand for learning how to design them. That is why I believe that exercising our democratic rights is key: Those who seek to bring beauty back to their communities should invade their city councils and demand it. Threaten to vote the ins out if, say, municipalities do not act to even the playing field for major architectural commissions so that traditionalists have a fair chance to beautify the public square as well as the residential neighborhoods. If it is true that most people prefer traditional styles – and I believe it is – then it will happen.

But maybe even that is unlikely, perhaps most unlikely of all. The people using their votes to demand that government do what they want? Yes, it is a stretch, but the alternative may be to just get used to ugliness. This, one might argue, is what we already have done. Still, all of these conversations on how to advance the classical revival add value to the discourse. I hope that this new blog can help Traditional Building and Period Homes move that discourse toward a future that doesn’t keep poking us in the eye.

For 30 years, David Brussat was on the editorial board of The Providence Journal, where he wrote unsigned editorials expressing the newspaper’s opinion on a wide range of topics, plus a weekly column of architecture criticism and commentary on cultural, design and economic development issues locally, nationally and globally. For a quarter of a century he was the only newspaper-based architecture critic in America championing new traditional work and denouncing modernist work. In 2009, he began writing a blog, Architecture Here and There. He was laid off when the Journal was sold in 2014, and his writing continues through his blog, which is now independent. In 2014 he also started a consultancy through which he writes and edits material for some of the architecture world’s most celebrated designers and theorists. In 2015, at the request of History Press, he wrote Lost Providence, which was published in 2017.

Brussat belongs to the Providence Preservation Society, the Rhode Island Historical Society, and the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, where he is on the board of the New England chapter. He received an Arthur Ross Award from the ICAA in 2002, and he was recently named a Fellow of the Royal Society of the Arts. He was born in Chicago, grew up in the District of Columbia, and lives in Providence with his wife, Victoria, son Billy, and cat Gato.