Carroll William Westfall

Modern Pantheons

So form follows function? But when the function is not needed, so is the building. The plan is the generator? Then the exterior as an afterthought. Such buildings are rarely memorable, and their destruction is no great loss. But we value and keep buildings that are memorable because they are beautiful, or they convey a sense of grandeur, dignity, importance, or even eternity, or they dominate and thereby make a coherent whole from an otherwise random assembly of buildings, and some serve all three purposes

The Pantheon in Rome, a domed tholos with an attached temple front, is memorable, and a much used model for others. Part of its fame comes from its interior. Its purpose was to offer veneration to pagan gods, but that role and the functions serving it changed in 609 when it became a Chrisian church, which it still is. Damage has been minimal: The bronze, gilded stars in each of its dome’s coffers are gone, and the walls’ upper level was altered in 1747 with one panel returned to its original form in the 20th c. Various post-medieval paintings and sculptures occupy niches, and inconspicuous tombs of some medieval city officials were added, as was one for Raphael, the first for a half dozen architects and artists to follow, and the unavoidable tombs of the first two kings of Italy.

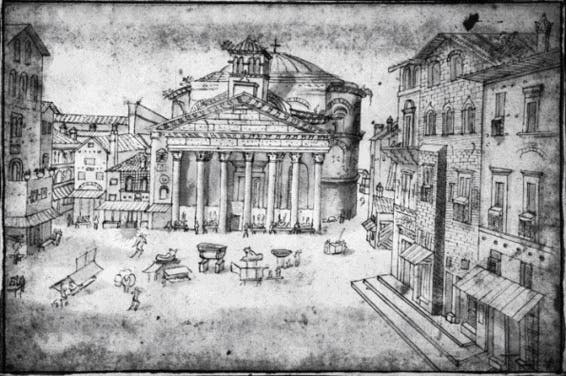

The exterior suffered the most. Originally within a precinct open to the sky with steps ascending to the great temple front, now a person descends across a busy Roman piazza elevated by the earth and debris deposited by Tiber River floods and the depopulation.

Our illustration is from around 1450 when the city recovered and Pope Nicholas V (1447-55), Leon Battista Alberti’s employer, repaired the lead roof. In the 17th c. the small belfry at the pediment’s peak was replaced by a pair of belfries called the asse’s ears that were themselves later removed. Only seven of the original monolithic, unfluted columns in the front rank are present, the eighth and one each in the two rows behind were replaced by the ramshackle shop we see. It is long gone, and the three lost columns have been replaced with pink shafts that contrast with the gray originals. Their crisp Corinthian capitals are also new, the others are eroded almost down to their bells, perhaps, as the late Ronald Malmstrom suggested, by a millennium of kids using them as targets for their rocks. Long gone is the bronze figuration in the pediment and more recently the bronze ceiling for late 17th c. Vatican fortifications, but, remarkably, the doors are original and still turn on their hinges.

Only fragments of the marble cladding of the great domed cylinder retain. Behind the temple front a flat section has marble inserts paralleling the pediment’s racking cornice, the topic of innumerable conjectures. Mark Wilson Jones has suggested that the pediment’s pieces had been fabricated before problems in logistics and construction prevented using the shafts of 50 Roman foot columns proportioned for the pediment. To complete construction the present 40 footers were substituted, leaving that trace above. His redrawing showing 50 footers quite convincingly improves the building’s appearance, making this, the most memorable gift of ancient Roman architecture, look a bit spindly.

Its purpose of serving veneration is like that of several of its successors. A beautiful and familiar example is John Russell Pope’s Jefferson Memorial in Washington from 1937. Its design exploits its landscape setting on a site suggested by the 1901 McMillan Commission Plan and endorsed by President Franklyn Roosevelt. While Rome’s urban Pantheon invites the visitor in from the city, Pope’s peripteral colonnade, Ionic rather than Corinthian, opens the interior to the city Jefferson helped bring into existence

Another commemorative shrine, but this time functioning as an auditorium, is the Sun Ya Sen Memorial Hall by Lü Yanzhi in Guangzhou (formerly Canton) from 1929-31. Sun Yat Sen, the revolutionary Father of the Country who founded the modern state in 1911, destroyed centuries of dynastic rule. Occupying a site important in events in his revolutionary accomplishments that is now in a large park in the major trading city with the west, it quite appropriately contains a hall holding more than 3,000 people and was funded by popular contributions. Its Chinese architect, who had lived in Paris and was a Cornell graduate, brilliantly adapted western motifs to Chinese configurations and motifs here and at Sun Yat Sen’s Mausoleum in Nanjing. Here the temple front has been replaced by a column screen, a motif that fronted Chinese temples such as the Temple of Supreme Harmony in Beijing’s Forbidden City.

A much more literal evocation of the Pantheon was intended make a more direct connection with the western world at the 1917 Great Auditorium with a capacity of almost 1,000 for the new Tsinghua University in Beijing.

Its architect, Henry K. Murphy, had earlier employed Lü Yanzhi, and the president of the new university asked Murphy, his Yale classmate, for a campus plan. The involvement of another top government official, a 1900 alumnus of the University of Virginia, may account for its similarity to Jefferson’s Rotonda. The dome’s tholos is enclosed within a brick Greek Cross whose faces rise to a pediment that on the front suggests of a temple front. While Lü’s later building will quite properly be much more deeply immersed in traditional Chinese architecture, Murphy’s clearly signals China’s desire to import domestic ideas for adaptation to China’s needs. His career with several long sojourns in China produced several educational buildings there.

As at UVA, use as a library was common for these modern Pantheons. After Jefferson anchored his academical village with the Rotonda, others followed. McKim, Mead, and White compressed UVA’s landscaped academic village to fit New York’s rigid quadrangular urbanism in 1894 for Columbia University crowned by the memorial Low Library.

The university’s president Seth Low assured that its name would honor his father. Increasingly dysfunctional as a library, it was replaced in 1934 and converted to administrative offices, its great columnar propylaea and low Pantheon-dome remaining the dominant element in the Morningside Heights campus.

Another Pantheon, this one a railroad station in Richmond, used its dominating bulk to draw passengers to trains that had formerly run down Broad Street to the edge of the downtown. Set well back from the street and serving several railroads, it allowed trains to return to their main lines by looping through an area now devoted to other uses after Amtrak abandoned it in 1975, Becoming the home of the Science Museum of Virginia saved it from demolition. A copper-clad dome rises above the Indiana limestone encasement, its frontispiece not a temple front but an entrance propylaea with six Tuscan columns flanked by a bay framed by pilasters and holding an arch beneath a window, all capped with a parapet above a cornice that runs to the pair of recessed three-bay wings.

The Pantheon as dominant element in urbanism played a final role when classical models were being jilted in favor of Modernist designs. Manchester, before 1800 a rural town in northern England, became cottonopolis fed by America’s slave-produced cotton where workers endured the constant murky blackness of coal smoke and damp and mill owners and brokers relished the motto, “Where there’s muck there’s money.” Its brick warehouses and factories tutored Karl Friedrich Schinkel, and its Town Hall (1868-77) and the University of Manchester’s several phases (1869-1902) by the prolific Mancunian Alfred Waterhouse proclaimed its wealth, newly visible now that the black is gone.

The 1927 competition for the Manchester Central Library (1930-34) and another for the Town Hall Extension (1934-38) were won by E. Vincent Harris. Their adjoining sites exploit the potential of a crucial urban site where a major street from the University district enters the compact central city. The target is the low-domed Pantheon-library whose Corinthian columnar propylaea has a Tuscan attic level colonnade above a fenestrated arcade and followed by a drafted ashlar wall. A carefully studied classical miniaturization of the Royal Albert Hall, it stands free within an ample plaza and deflects traffic to the right alongside the Town Hall Extension or left to a higher building commensurate with the older commercial buildings. The Town Hall Extension’s articulated façade and pitched roof present a monochromatic abbreviation of Waterhouse’s colorful Town Hall invisible behind it.

The Pantheon haunted Modernists who sought to nullify antiquity but used its negative to proclaim their presence. What, after all, is Fank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum (1956-59) but an upside down Pantheon? Another was by Haig Jamgochian (1924-2019), a Richmond native and local eccentric educated in architecture at Virginia Tech and Princeton. His Merkel Insurance office building (1965) is a domeless Pantheon perched on legs, wider at the top than below. Wrapped in battered aluminum, it is hidden on a side street. A more conspicuous thumb in the eye is Gordon Bunshaft’s Hirshorn Museum (1969-74) on the Mall in Washington, a pill box with its guns trained on Pope’s National Archives Building, the clear winner in that faceoff.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.