Rudy Christian

Made by Hand–or Made by the Trades?

I’ve spent a lot of time and words talking about the importance of making things by hand, but recently I’m finding reason to question the validity of that statement. One of my favorite ways of describing how the world we live in affects the way we think is to point out that in modern times we spend most of our lives in environments where everything that surrounds us is manufactured. Rather than being able to appreciate the skill of the maker, with whom we might consider spending our hard-earned cash, we seem to spend most of our time looking for cheaper and glitzier items that ultimately, and usually in short order, become outdated, dysfunctional or simply unwanted. Throwing something away in the world we live in is largely impersonal; at best, we attempt to sooth our karmic conscience by “recycling.”

When objects had souls

In the early 19th century, in most of the world, and well into the latter part of the 19th century in most rural areas - a stone’s throw in time for homo sapiens – most, if not all, of what we connected with in our environment was fashioned by hand. Inanimate objects had souls of sorts because they represented the work of the skilled tradesperson and reminded us of the value of the trades in the world we lived in.

Today our view of the trades is through plywood barriers around construction sites and flybys of workers along the mass transit lines as we whisk by in air-conditioned tubes bound for somewhere important. When we walk into a big- box store to ply our plastic cash, the importance of the trades is the furthest thing from our minds as we walk up and down aisle after aisle of soulless merchandise.

To me, this understanding of how we are affected by a world full of stuff built by robots and a nearly complete disconnect with what the trades mean in our lives--the absence of “hand made” items creating a sterile rather than a holistic world--made clear sense until I heard episode #454 of “This American Life” on January 7th on public radio. The episode was called “Mr. Daisey and the Apple Factory,” and what I heard was “Act One: Mr. Daisey Goes to China.”

Ira Glass is the host of “This American Life,” and his show is always the highlight of my Saturday afternoons, when I’m lucky enough to be near a radio. His shows often reflect a cross section of our lives that most people might feel a little funny talking about, or his guests will discuss a topic that many people might consider “sensitive;” but what he is really providing us is a comfortable(ish) view of the world around us that is real and exists whether or not we choose to connect with it.

There are more handmade things now than there have ever been in the history of the world.

In the episode at hand, Ira has taken an excerpt from one of Mike Daisey’s stage monologues and adapted it for radio. The monologue is based on Mike’s experience, as a self-professed high tech “geek,” when he came across a story of another geek having purchased a brand-new smart phone and realized it had pictures on it that were taken when the camera was being tested at the factory and hadn’t been erased. The pictures were of the inside of the Chinese electronics manufacturing facility where the smart phone had been made, but they weren’t pictures of what we would think of as a factory or manufacturing facility. They were pictures of conveyor belts, pallets and people.

Here are Mike’s own words, taken from the transcript of the show, expressing what he thought about all this. “It’s actually hard now to reconstruct what I did think," he said. "I think what I thought is they were made by robots. I got an image in my mind that I now realize I just stole from a '60 Minutes' story about Japanese automotive plants. I just copy and pasted that. I was like, pwop, Command-V, pwop. It looks like that, but smaller, because they’re laptops.” But what Mike realized later is they weren’t manufactured by robots; they were made by hand, a fact so unbelievable it motivated him to travel to Shenzhen China to see for himself and meet the people who worked in the electronics industry.

And after visiting Shenzhen and meeting the people Mike says, “When I leave the factory, as I can feel myself being rewritten from the inside out, the way I see everything is starting to change. I keep thinking how often do we wish more things were handmade? Oh, we talk about that all the time, don’t we? ‘I wish it was like the old days. I wish things had that human touch.’ But that’s not true. There are more handmade things now than there have ever been in the history of the world.” If you think of it by how much stuff we buy, he’s right.

BioRobots

Mike also points out that in an economy where labor is practically free, there is no need to invest in robots. You just turn the people into them. And in eight or 10 years, when their hands are too crippled to work correctly, you throw them away and hire their children. It reminds me of the stories I’ve heard of Henry Ford’s first assembly line, where he hired skilled wheelwrights, coach makers and other out-of-work tradespeople, only to have them walk out when they realized they weren’t being appreciated for their skills but instead being asked to become part of the machine. Today, the slabs of glass we all feel are a crucial part of our modern life are manufactured by poorly treated human machines who don’t walk out of the factories because they have nowhere to go.

So my big-box analogy has gone by the wayside. I need to be more careful how I use the term “handmade” and accept the fact that “handmade” and “made by the trades” are neither mutually exclusive nor interchangeable terms. I also need to accept the fact that in today’s world, “handmade” isn’t necessarily a good thing.

Rudy R. Christian is a founding member and past president of the Timber Framers Guild and of Friends of Ohio Barns and a founding member and executive director of the Preservation Trades Network. He is also a founding member of the Traditional Timberframe Research and Advisory Group and the International Trades Education Initiative. He speaks frequently about historic conservation and also conducts educational workshops. Rudy has also published various articles, including “Conservation of Historic Building Trades: A Timber Framer’s View” in the “APT Bulletin,” Vol. XXXIII, No. 1, and his recent collaborative work with author Allen Noble, entitled “The Barn: A Symbol of Ohio,” has been published on the Internet. In November 2000, the Preservation Trades Network awarded Rudy the Askins Achievement Award for excellence in the field of historic preservation.

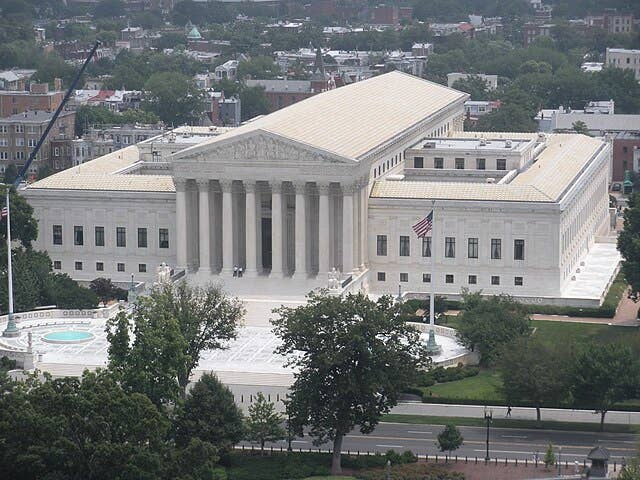

As president of Christian & Son, his professional work has included numerous reconstruction projects, such as the historic “Big Barn” at Malabar Farm State Park near Mansfield, OH, and relocation of the 19th-century Crawford Horse Barn in Newark, OH. These projects featured “hand raisings,” which were open to the public and attracted a total of 130,000 interested spectators. He also led a crew of timber framers at the Smithsonian Folk Life Festival, Masters of the Building Arts program, in the re-creation and raising of an 18th-century carriage house frame on the Mall in Washington, DC. Roy Underhill’s “Woodright’s Shop” filmed the event for PBS, and Roy participated in the raising.

Christian & Son’s recent work includes working with a team of specialists to relocate Thomas Edison’s #11 laboratory building from the Henry Ford Museum to West Orange, NJ, where it originally was built. During the summer of 2006, Rudy; his son, Carson; and his wife, Laura, were the lead instructors and conservation specialists for the Field School at Mt. Lebanon Shaker Village, where the 1838 timber frame grainery was restored. In July and August 2008, Rudy and Laura directed and instructed a field school in the Holy Cross historic district in New Orleans in collaboration with the University of Florida and the World Monuments Fund.

Rudy studied structural engineering at both the General Motors Institute in Flint, MI, and Akron University in Ohio. He has also studied historic compound roof layout and computer modeling at the Gewerbe Akademie in Rotweil, Germany. He is an adjunct professor at Palomar College in San Marcos, CA, and an approved workshop instructor for the Timber Framers Guild.