Carroll William Westfall

“Look at Me. I’m on the Mall!”

We put our best face forward in public where we join with others in contributing to the common good that protects our individual liberties. And so too with our buildings: their faces present their commitment to serving and expressing the particular purposes of those who built them.

These buildings can be divided into three ranked categories: public buildings whose purposes serve the common good; private buildings accessible to the public as seats of cultural and social institutions; and private buildings serving as residences and commercial enterprise.

In the western tradition where our nation resides these ranks correspond to the relative importance of the various purposes of the authoritative civil order, with the buildings serving the three ranks clear for the eye to see. Historic cities and old towns and villages offer us a broad and sometimes bewildering variety of buildings, but their roles and ranks in serving the civil order’s ends is easily deciphered. With knowledge of the ups and downs of the political, economic, and cultural history of a place we obtain an enriched reading of the urban fabric.

Washington D.C., the heir of antiquity built ex novo by a generation steeped in ancient knowledge, was designed by President Washington, Secretary of State Jefferson, and French immigrant Pierre Charles L’Enfant. Theirs was, and again became, a perfectly coordinated urban and architectural counterpart to the newly constituted national governmentthat built it.

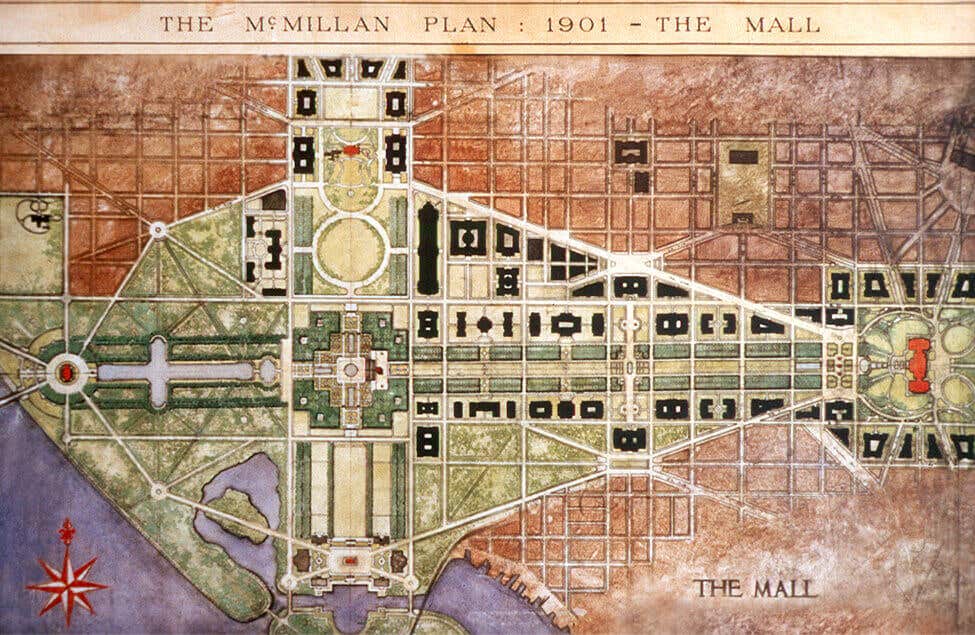

Within the ten mile square (cut down in 1847) they laid down three distinctive urban elements. For residential and commercial activities they provided a rectangular grid like the one being extended westward from the Ohio River. For the second they expressed the nation’s authoritative role in the federal system by inserting broad avenues that knitted together and connected particular topographic features and institutional sites. And to serve the premier rank they bound together the nation’s two highest ranked authoritative institutions with one of the broad avenues and two great swaths of land, each exploiting the two most important topographic features.

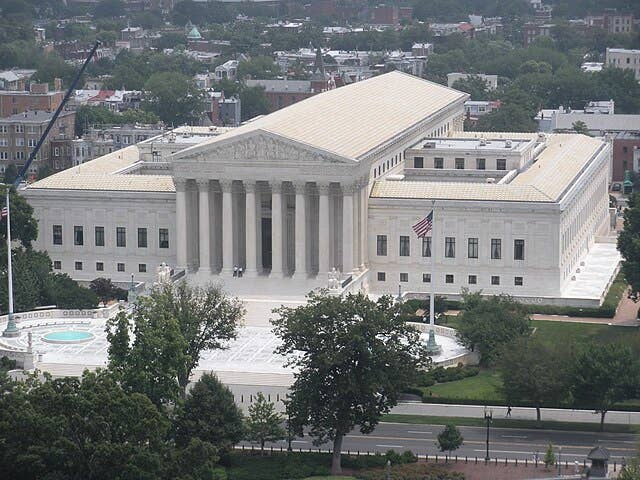

On one, that L’Enfant called a hill awaiting a monument, they placed the new nation’s Capital that gave the hill its new name. A century or more was needed to reach its present, amended form. Its great temple front faces a broad, eastward running avenue, and its other face looks westward with the new nation growing beyond a broad greensward. The ultimate models for this side are the gardens using perspective to order the landscape of noble villas of central Italian barons and French chateaux, most notably those of André Le Nôtre for Louis XIV’s planned axial extension of the Louvre through the Tuileries and to the horizon and for Versailles’ great garden where a basin was to receive ships traversing the country on never-built canals. In England this parti furnished long tree-lined walks such as the fashionable promenade in Saint James’s Park, London. Its name, the Mall, was applied to this broad turf that, with its bordering canal and streets, was to attract the capital’s social and economic life, residences, social centers,gardens, embassies, theaters, etc.

The other feature, the Potamic River, connected the new nation with its European predecessors. The impressive President’s House headed a briefer greensward with its neighbors to be seats of executive departments. In 1836 the Treasury Department unfortunately blocked Pennsylvania Avenue’s axial connection to the Capitol; the Department of State, War, and Navy Building (now the Executive Office Building) was begun in 1871 on the White House’s other side.

Where the two greenswards intersected the first president was to be honored; the great obelisk begun in 1848 was slightly dislocated.

The plan’s lucid simplicity smartly separated the three ranks of buildings while connecting them to make a unified urban whole.

This “kite plan” offered a visual diagram of how the Constitution would unite the people and their states into a “more perfect union.” It drew from the broad range of old world models and from one that is too seldom noted in this context, namely, the 1699 plan that Governor Nicholson used for Virginia’s new colonial capital of Williamsburg. He had an axial street with shops and residences connect the College of William and Mary and the new Capitol. Intersecting it he placed a broad, tree-lined greensward headed by the governor’s mansion and running across to a creek; it hosted horseraces. Alter the sizes and add Pennsylvania Avenue and you have the new nation’s capital kite plan.

Williamsburg was built with red brick; Washington’s most important building were stone. Trained architects were scarce, but many of the new Americans were well educated in matters architectural and equipped with books providing examples of the individual pieces and whole compositions for buildings. Theirs are carefully built simplifications of European predecessors that, as with the Constitution, they drew most heavily on English sources.

These early American builders and architects remained distanced from the radical upheaval in architectural thought that had transpired on the Continent during the previous century. Architecture’s connection with the natural law premises of the civil order had been cancelled, and so too the objective status of the beautiful as the counterpart to the good. The soul-fulfilling beautiful was set aside in favor of immediate pleasures offered by sight. Likened to the pleasures of the palate, the standards were those of taste, a possession of each individual. Taste, a judgment relative to the individual, was beyond the reach of reason and resided in the eye of the beholder.

Meanwhile the discipline of history was developing, and it soon drew the arts into its chronology. With taste displacing beauty and therefore separating it from reasoned judgments about the good, architecture was designated one of the fine arts whose works were commanded by artists and by the influences of successive eras. Historians sliced the multimillennial traditions of architecture into successive styles, with the ancient world’s labeled the classical. The American founders were largely untouched by these developments. Instead, they were deeply entrenched in an admiration of antiquity, that is, the classical. For the new nation’s buildings they would draw on the tradition that flowed from antiquity available mainly through books and recent precedents.

By midcentury the classical was waning as romanticism lured people to take pleasure in exotic historical styles. On the Mall in 1847 construction was begun on the castellated red-brick Smithsonian Institution. In 1851 the Mall itself began to be replanted as a rich, arboreal. American landscape. And in 1873 an extravagant medieval railroad station opened in the Mall’s picturesque landscape.

The classical, architecture’s grandest tradition, surged back at Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition. Its central area was Mall-like with a domed administrative headquarters beyond the building celebrating the nation’s achievements. The expo’s popularity launched the City Beautiful movement and a Senate Commission in 1905-06 that called on the men who made the Expo to restore, expand, and modernize Washington. At the heart of their 1912 Plan are today’s intersecting Malls that were “intended to form a unified connection between the Capitol and the White House, and [along the Mall’s sides] … to furnish sites for a certain class of public buildings [devoted] to scientific purposes and for the great museums.”

The Mall’s forest and several buildings were cleared away and replaced: theNational Museum of Natural History (1906, mostly Charles Follen McKim); Agriculture building (1914); Freer Gallery of Art (1916; Charles Platt) to house an industrialist’s collection of art objects; and National Gallery of Art (1936; John Russell Pope) for Andrew W. Mellon gift of old master paintings and funded by donor and the nation. Elsewhere throughout the nation the classical proliferated, and in Washington as well, for example with Pope’s National Archives (1929) anchoring the Federal Triangle and Jefferson Memorial (1937) built despite Modernists’vigorous opposition.

They invested the nation’s highest rank of public and cultural buildings with beauty as the counterpart to the nation’s common good. Like good citizens, they exemplified decorum in fulfilling Cicero’s admonition that “it is our duty to respect, defined, and maintain the common bonds of union and fellowship subsisting between all members of the human race.” (de Off., XLI)

The U. S. Commission of Fine Arts was established in 1910 to assure the plan’s faithful execution, but it failed miserably when construction resumed after the Depression and the World War. Given carte blanche on the Mall were explicitly anti-traditional buildings whose Modernistdesigns had been developed to serve commerce, the lowest rank of buildings. Modernism wasquickly grabbed by attention-seeking individuals and cultural institutions. Throughout the nation and along the Mall the public faces of buildings no longer expressed the role of the nation’s authority in making e pluribus unum. The Mall’s new building present unique, creative exteriors to call attention to their interiors’ displays. They point to what they have achieved for themselves while on the Mall their presence is self-aggrandizement scanting their contribution to this modern, uniquely democratic nation.

This shift helped sanction the hegemonic rise of anti-traditional Modernism’s mediocre buildings, even those serving top-ranked public and cultural roles. Consider the National Museum of American History (1955 by the long-dead McKim firm); theNational Air Museum (1964, Gyo Obata); and Modernism’s triumph, the Joseph H. Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (1969), by Gordon Bunshaft, then a leader in designing Modernist commercial towers and cultural institutions, A doughnut on stubby legs, it is an obvious critique of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York City and a redoubt with a gun port pointed at Pope’s art palace.

Modernism triumphant! Now buildings will deploy transient fashions with individual creativity and exteriors that express interior content. Rejected is any engagement with the traditional architecture that connects these cultural institutions with those of the civil order. Instead, they shout, “Look at me! Forget the rest” The National Gallery’s East Wing, the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery; the National Museum of African Art; the Holocaust Memorial Museum; the National Museum of the American Indian; the National Museum of African American History and Culture; and yet two more, for Women and Latinos, searching for sites.

And individualism triumphant! Along the Mall between the nation’s two most important buildings, and proliferating elsewhere as buildings serving high ranked purposes, are new buildings that suggest they are peers to buildings of the lowest rank. This inversion acknowledges, and contributes to, Modernism’s undermining of our the authority the nation assumes to protect our liberty to pursue and enjoy private interests.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.