Carroll William Westfall

Let’s Talk About Beauty Again

Traditional buildings offer beauty, something we don’t much talk about when we talk about architecture. We know that beauty is important, and we have a sense of its presence when it is present, but we have a hard time defining it or putting words to what we see and taking the time engaged that is needed for it to capture us. Traditional buildings are more often called beautiful than modernist ones, and its presence surely plays a role in the increased preference for new traditional buildings. Perhaps increased talk about beauty will amplify its appeal and expand its presence.

An easy definition of beauty is that it is what is added to buildings beyond their utilitarian roles of providing shelter and comfort. Beauty, like justice, is what we seek when we seek what Aristotle called the good life when we live in what the Greeks called a political community and the Romans called a city. (1) Both beauty and justice had indubitably objective standing as a part of Nature that Norris Kelly Smith described as a stable and “lawful universe that possesses … reality and intelligibility.” Although the Greeks lacked a word specifically for beauty, their word kalon (Καλός) served because, as Wladyslaw Tatarkiewicz explained, it referred to that which “pleases, attracts and arouses admiration,” and as the Delphic oracle said, “The most just is the most beautiful.”

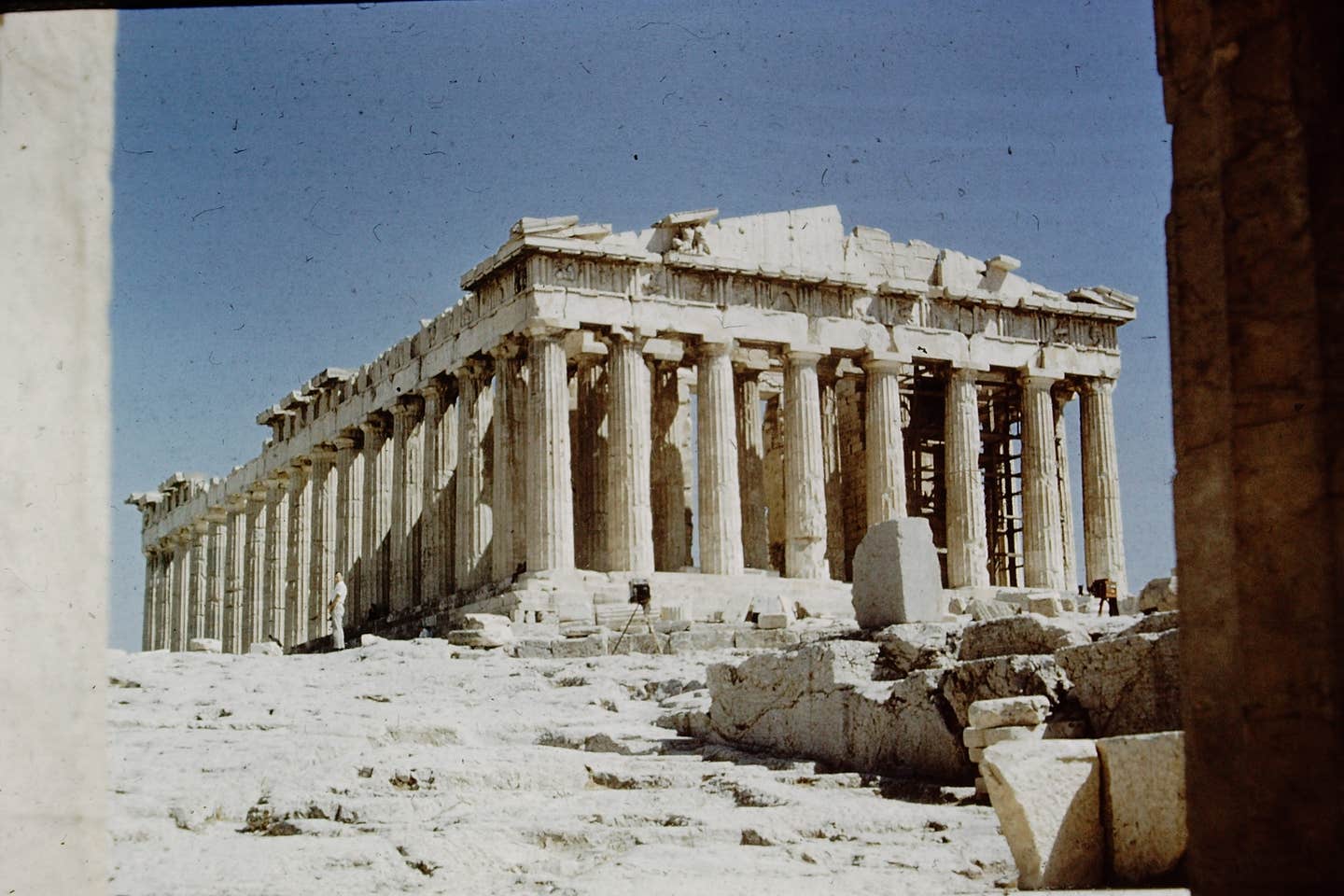

Vitruvius’ trilogy of firmitas, commoditas, and venustas ends with delight rather than one of Latin’s stronger words for beauty. The important buildings, especially the temples, required an additional triplet with two taken from the Greek. Symmetria, or the binding together of the building’s pieces, and included honoring Pythagorean proportionality, exemplified by the well-formed human figure, and numerology and geometry. Eurythmia would temper the symmetria with reasoned judgment to assure the visibility of the symmetria. An finally, decorum, the thoroughly Roman demand that the rank of the building’s status, like that of the individual in the Roman world, display its place in the civil and therefore in the cosmic order: therein resided its beauty.

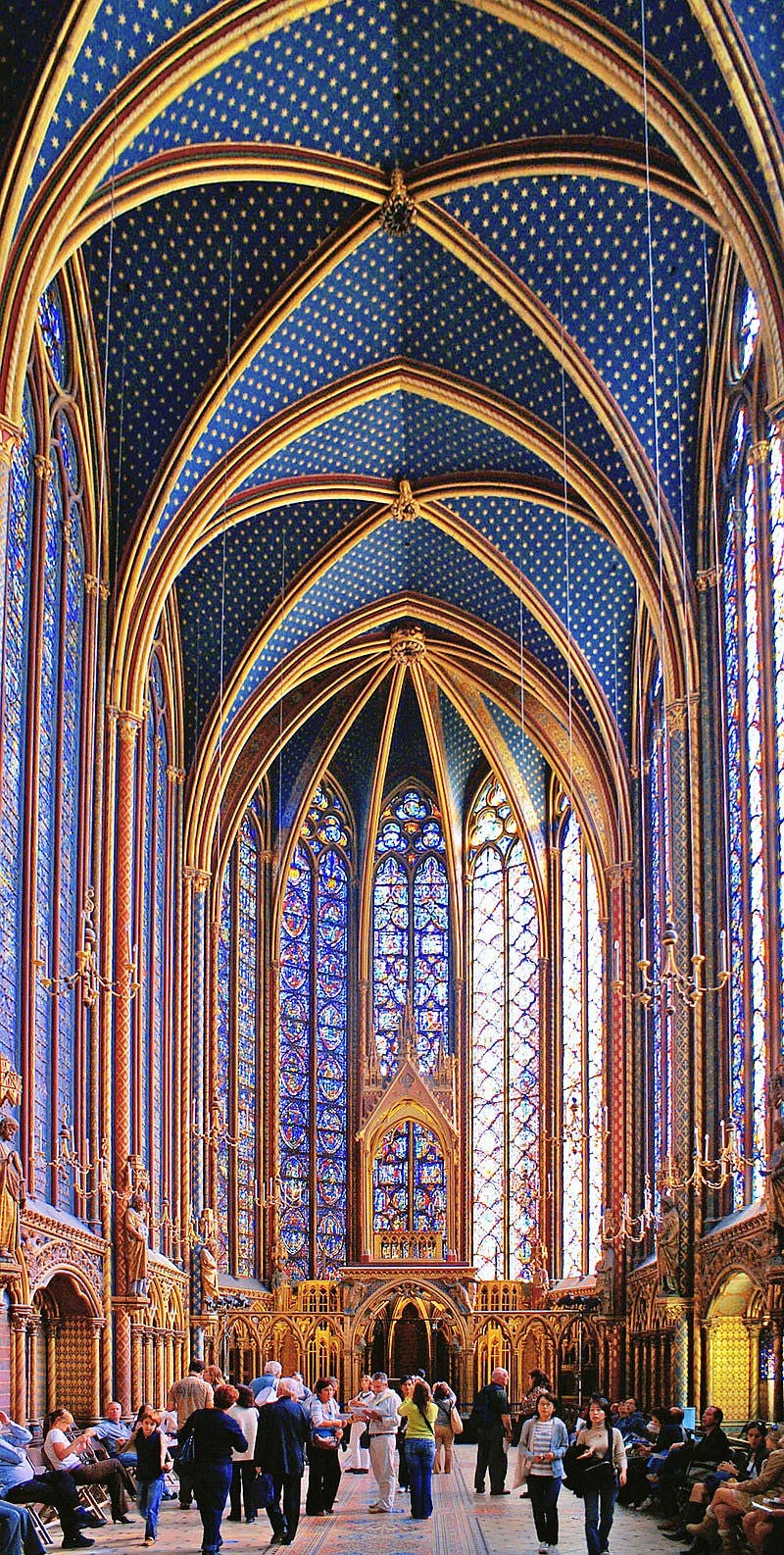

(2) In the Christian millennium that transformed the Roman legacy, beauty in buildings revealed God’s creation and taught the Church’s doctrines. A church building in the city of man stood for the City of God. In the 13th c. Saint Thomas Aquinas, who interchanged beauty (pulchritude) with decorum, wrote that beauty is "that which, when seen, pleases" with its properties of integrity, proportion, and clarity, terms that call for completeness, a reasoned relationship among things and between them and their Creator, and a luminous and colorful splendor.

Two centuries later the trained lawyer Leon Battista Alberti adapted ancient theories to serve in this Christian world. In his first, and more familiar, definition of beauty he calls for completeness: nothing can be added, subtracted, or altered without damaging a building’s beauty. In Book IX he expands beauty’s reach and content by requiring that proper number, finishing, and collocation (or quantity, craftsmanship, and assembly) achieve the concinnity (or order, harmony, and proportionality) exhibited in Nature or, as he wrote elsewhere, “Nature, that is, God.”

(3, 4) Here on the threshold of the modern era five points about beauty in architecture stand out. 1. A building embodies beauty. 2. The beauty’s source is Nature’s order, harmony, and proportionality. 3. The beautiful building has a reasoned relationship to the good its purpose is to serve. 4. Like that purpose, it must take its proper place in the urbanism it joins. 5. The judgment and skill of the architect must temper the implementation of that order.

In the centuries since the 16th c. the Reformation has forever altered the relationship between Church and state and between those and individuals, and mathematical empiricism has come to enable us to exercise control over the behavior of material (small n) nature. Meanwhile, those five points have been gradually shed and modernist architecture has achieved dominance.

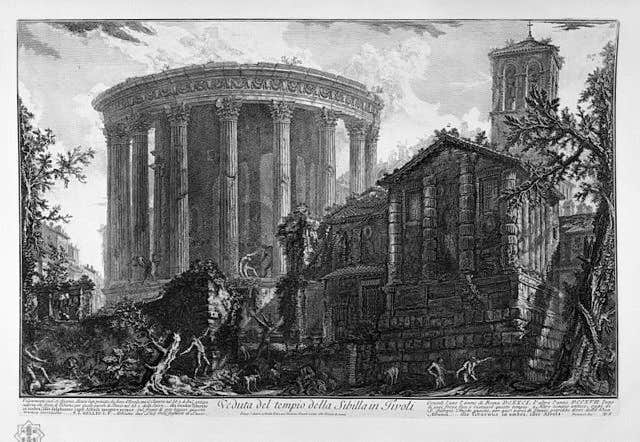

Three very different factors are in place today. One is beauty’s rejection as an enduring, objective quality and its acceptance as a quality relative to judgments made in the eye of individual beholders and changeable as customs and fashions change. It presence is still announced by sensations felt in the emotions, but that’s the end of it. The feeling its presence provokes is unshareable and beyond dispute. (5) To account for this sensation the sublime was invented to account for the thrill found in encountering the ravages of time, the power of thunderstorms, and the threat of wilderness, and the sight of virile buildings unlike anything seen before, while beauty became the neutered pleasure of well-tended gardens and frilly ornaments.

The second factor is the history of architecture’s replacement of guidance from theory and apprenticeship. As always, new buildings are made out of precedents. In traditionally, precedents were found in treatises and, more powerfully, in existing buildings that inventive modifications would adapt to current conditions in particular places. But now, buildings that histories plant in time provide precedents. The style based purely on its formal appearance replaces interest in the role it renders to a place. The histories collect stylistic look-alikes into groups and attach them to successive eras according to two rules: one style per historical era, and no repeats. Earlier styles are outlaws in later periods, it tradition is rendered moot with the most recent fashionable style furnishing the precedents. The succession of styles rather than by the quality of the beauty’s forms is applauded as progress.

And the third factor is architecture’s displacement from its traditional home among the liberal arts, where its beauty was the complement of justice, and its absorption of the empiricism of the natural sciences and their alliance with technology. Reasoned judgments concerning service in human affairs that theory promoted has been replace names and dates in data-driven, style-based histories that gave transient styles primacy with utility tucked inside in the transformation of a humanist architecture into a machine age architecture.

As these factors were developing the Vitruvian trilogy was dismantled and the roles of symmetria, eurythmia, and decorum were dismissed. A building’s appeal was delegated to the feelings, disengaged from concerns for the moral and common good and with no contact with the intellect. Buildings offered sublime or delightful emotional stimulation. The copious menu of variations on beauty that architecture had offered since antiquity was reduced to the measly fast-food combo of utility and beauty or, as Adam Smith wrote in 1759, “That utility is one of the principal sources of beauty, has been observed by every body who has considered with any attention what constitutes the nature of beauty.” “Character, effect, variety—in a word, all those beauties that are found in buildings or that men seek to introduce into architectural decoration—naturally emerge from any disposition that embraces fitness and economy.”

In the next century Smith’s formulation of utility and beauty would deteriorate into utility or beauty as technical progress replaced invention within tradition as the driver of architectural designs following Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand’s instruction that would become the formula that form follows function. Then, modernist architects embraced machines as emblems of progress: (6) “A house is a machine for living in” (LeCorbusier in 1923), and beauty is “a florid aestheticism, as weak as it was sentimental” burying the “verities of structure under a “welter of heterogeneous ornament” (Gropius in 1935). (7)

Acknowledging that his machine age buildings were unpopular, Gropius argued they would eventually find public acceptance, but acceptance remains largely limited to its fans. Increasing popular disapproval is voiced about modernist exercises involving the important buildings that Vitruvius said had to honor decorum to achieve beauty. (8) With a few notable exceptions, aging modernist buildings are discarded when the their utility becomes unserviceable and new styles capture the market and the public imagination.

Solipsistic and narcissistic modernist styles are designed to excite the eye. Illusory, insubstantial ideologies explain practices that market forces and popular media sustain. Unpopular buildings proliferate in an increasingly inhospitable urbanism undermining the cherished continuity of places that are homes where reasoned judgment is used to seek justice and pursue happiness.

Traditional architecture is necessary for the building and the constant rebuilding of places that promote human flourishing and facilitate the Delphic oracle’s union of beauty and justice. Buildings in any stye can offer sights that stir our feelings, but only traditional buildings, old and new, invite the extended engagement needed to gain beauty’s richer rewards. To build them and to engage with beauty’s presence the mind with its memory must muse about what you’ve felt, then have the intellect expand upon those musings, and finally relish the perception of beauty entering the heart, the seat of the soul and our deepest and most personal possession. Talking about beauty in these terms and with others will help restore its presence in what we build and in the places where we live.

Carroll William Westfall retired from the University of Notre Dame in 2015 where he taught architectural history and theory since 1998, having earlier taught at Amherst College, the University of Illinois in Chicago, and between 1982 and 1998 at the University of Virginia.

He completed his PhD at Columbia University after his BA from the University of California and MA from the University of Manchester. He has published numerous articles on topics from antiquity to the present day and four books, most recently Architectural Type and Character: A Practical Guide to a History of Architecture coauthored with Samir Younés (Routledge, 2022). His central focus is on the history of the city and the reciprocity between the political life and the urban and architectural elements that serve the common good. He resides in Richmond, Virginia.